John Bradshawe: Marple's Most Famous Son...

Marple Hall was purchased by Henry Bradshawe in 1606, when the lands of Marple and Wybersley manors were divided by their owner, Sir Edward Stanley, and sold to four of his local tenant farmers.

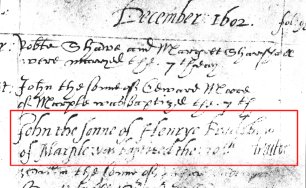

On his death, in 1620, Henry was succeeded by his son Henry Bradshawe II. At this time Henry II was a widower with five surviving children from his marriage to Catherine, the daughter and heiress of Ralph Winnington of Offerton. They had been married in 1594 and had six children together before Catherine unfortunately died as a result of child-birth. Their first child, William, was baptised in January 1597 but died in November of that year. Two daughters were to follow in quick succession. Dorothy, who was baptised in August 1598 and Anne, in November 1599. The eldest surviving son, Henry III, was baptised in January 1601. He was followed by John in December 1602 and finally Francis, who was baptised on 13 January 1604. Sadly Catherine was buried just a few days later, on 24 January 1604.

On his death, in 1620, Henry was succeeded by his son Henry Bradshawe II. At this time Henry II was a widower with five surviving children from his marriage to Catherine, the daughter and heiress of Ralph Winnington of Offerton. They had been married in 1594 and had six children together before Catherine unfortunately died as a result of child-birth. Their first child, William, was baptised in January 1597 but died in November of that year. Two daughters were to follow in quick succession. Dorothy, who was baptised in August 1598 and Anne, in November 1599. The eldest surviving son, Henry III, was baptised in January 1601. He was followed by John in December 1602 and finally Francis, who was baptised on 13 January 1604. Sadly Catherine was buried just a few days later, on 24 January 1604.

Lord President of the High Court of Justice

The two daughters appear to have married well. Dorothy to George Newton, of Newton in Longdendale and Anne to John Fallowes, of Fallowes Hall in Alderley. Henry III became a Colonel in the Parliamentary Army and inherited Marple Hall from his father in 1654. Little is recorded of Francis, although he was know to be living in 1637 but John went on to become the Lord President of the High Court of Justice which condemned King Charles I to death and is said to be the most distinguished man that this part of Cheshire has ever produced.

Born at "The Place" or Peace Farm in 1602

John Bradshawe was probably born at 'The Place', later known as Peace Farm, which was located on the site of the Co-Op Service Station, at the corner of Stockport Road and Church Lane. Wybersley Hall has also been cited as John's birthplace and this is an argument that can never be firmly resolved, as there are no definitive records. The Stockport Heritage Trust obviously decided in favour of Peace Farm, which was demolished in 1936, as they erected a blue heritage plaque on the wall of the shop to commemorate it as the site of his birth - the only public tribute to a man who, for a period, held the highest office in the land. His baptism was entered in the Stockport Parish Register on the 10th December 1602, at some later date the word "Traitor" was added in a different hand.

Peace Farm on Stockport Road, probable birthplace of John Bradshawe

Well educated and prophetic

Bradshawe was partly educated at the Aldersey Grammar School at Bunbury in Cheshire, during which time he attended the Parish Church of St. Boniface (see Marple Hall Glass) and at Middleton Grammar School in Lancashire. He is also said to have attended King Edward's Grammar School in Macclesfield where, tradition has it, he wrote the following prophetic lines upon a gravestone there:

My brother Henry must heir the land,

My brother Frank must be at his command,

Whilst I, poor Jack, will do that

That all the world shall wonder at.

He subsequently studied with an attorney at Congleton before entering himself as a student for the bar at Gray's Inn, London, in 1622. He was called to the bar on 23rd April 1627, by which time he had reached 24 years of age. Having completed his studies, he returned to Congleton, where he practised for some years and, taking an active part in the town's affairs, was appointed High Steward. During this period he was also appointed Steward of the manor of Glossop, in Derbyshire.

In 1637 Bradshawe was named as Attorney General for Cheshire and Flintshire and was also chosen as Mayor of Congleton. He is said to have discharged this office with "ability and satisfaction", it being recorded that he was a "vigilant and intelligent magistrate, and well qualified to administer justice." Shortly after this, in 1640, he was appointed Judge of the Sheriff's Court in London's Guildhall, an office he held until his death. In the same year, he was also made Recorder of Newcastle, Staffordshire.

A move to London

A move to London

By 1644 Bradshawe had moved to London, where he continued to follow his profession. In October of that year he was employed for the first time on behalf of Parliament as one of the Counsel for the prosecution of the Irish rebels, Lords Macmahon and Macguire. The manner in which he conducted this prosecution and the resulting execution of the rebel lords must have pleased his employers, as he was ever more frequently engaged upon Parliamentary business.

In the following year he was made Junior Counsel for Parliament and on 6th October 1646, was nominated a Commissioner of the Great Seal, although this appointment was overruled by the House of Lords. He was, however, chosen as Chief Justice of Chester and Flint on 22nd February 1647 and formally appointed on 16th March that year. Also in 1647 he was to join forces with the celebrated William Prynne as one of the Counsel engaged in the prosecution of the intrepid Judge Jenkins, who, when impeached for treason before the Commons not only refused to kneel at the bar of the House, but had the temerity to call the place "a den of thieves."

So why was William Prynne "celebrated"?

Incidentally, if you're wondering why William Prynne was "celebrated", it's certainly worth a brief detour from the main story. Prynne was fined and imprisoned in 1633 and had his ears partly shorn for publishing pamphlets interpreted as an attack on Charles I and his Queen. Despite this harsh treatment he continued his pamphleteering from jail and in 1637 was again fined, sentenced to life imprisonment, deprived of the remainder of his ears, and branded with the letters S.L. (for seditious libeller). He was released from prison by the Long Parliament in 1640 and was voted financial reparation. During the Civil War, Prynne strongly supported the parliamentary cause in his writings, although he found himself opposing both Presbyterians and Independents due to his moderate views. He entered Parliament in 1648; but opposed the demand of the army for the execution of Charles I and so was expelled in Pride's Purge. He later wrote attacks against the Commonwealth, for which he was imprisoned (1650-53), and against the Protectorate, and later supported the Restoration of Charles II. In 1660 he became keeper of the records of the Tower of London. This could be described as a chequered career.

The English Civil War

Throughout the main period of Bradshawe's rise to eminence the English civil war was ongoing. The strained relationship between Parliament and the Sovereign had begun early in the reign of James I, who came to the throne in 1603. After Charles I succeeded his father in 1625, the relationship was to continue its decline. Eventually, after long years of dispute, the first major engagement of the civil war took place with the battle of Edgehill in October 1642. The next four years saw a great deal of indecisive conflict but with the emergence of Oliver Cromwell the Parliamentarians gradually gained the upper hand. At the battle of Marston Moor, in July 1644 and again in the battle of Naseby in June 1645, Cromwell achieved decisive victories and these set the scene for Charles' surrender to the Scots in 1646, signalling the end of the first civil war.

In 1647 the Scots delivered the King into the hands of Parliament, but Presbyterian rule had alienated the army and they responded to Parliament's proposals to disband it by capturing the King and marching on London. Army discontent became more radical and a desire grew to dispose of the King altogether. Charles refused to accept the army council's proposals for peace and in November 1647 he escaped and took refuge on the Isle of Wight. He was able to negotiate military support from the Scots and the second civil war began in the spring of 1648. Uprisings in Wales and England were swiftly suppressed by the Parliamentary forces and Cromwell defeated the Scots at Preston in August 1648. Charles's hopes of aid from France or Ireland proved vain, and the war was quickly over.

In 1647 the Scots delivered the King into the hands of Parliament, but Presbyterian rule had alienated the army and they responded to Parliament's proposals to disband it by capturing the King and marching on London. Army discontent became more radical and a desire grew to dispose of the King altogether. Charles refused to accept the army council's proposals for peace and in November 1647 he escaped and took refuge on the Isle of Wight. He was able to negotiate military support from the Scots and the second civil war began in the spring of 1648. Uprisings in Wales and England were swiftly suppressed by the Parliamentary forces and Cromwell defeated the Scots at Preston in August 1648. Charles's hopes of aid from France or Ireland proved vain, and the war was quickly over.

Parliament again tried to reach agreement with the King, but the army, now completely under Cromwell's domination, disposed of its enemies in Parliament by the expulsion of 143 members on the grounds that they were royalist sympathisers. This act took place in December 1648 and became known as Pride's Purge. Just a few weeks earlier Bradshawe's ascent continued when he was created a Serjeant-at-Law, by Order of Parliament.

Rump Parliament decides to try King Charles I

At the beginning of January 1649 the Rump Parliament, as the remains of the House of Commons became known, had decided upon the trial of King Charles I. They nominated a body of Commissioners and Judges who met on 10th January in the Painted Chamber at Westminster and elected Bradshawe to be their President. He was one of the Commissioners but was not present on that occasion. It was a job Bradshawe did not want and when he attended two days later he tried to relinquish the role to which he had been elected during his absence, making "an earnest apology for himself to be excused".

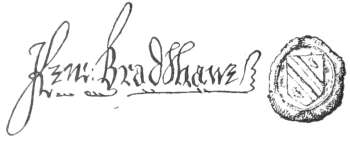

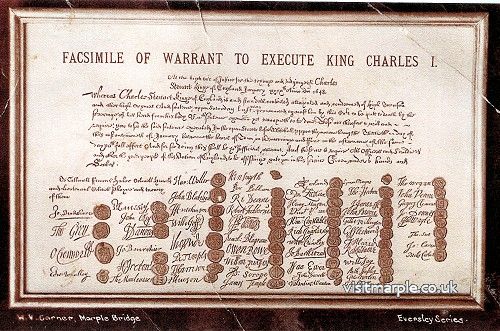

Bradshawe's efforts to avoid this momentous task proved of no avail and the Court proceeded to order "that John Bradshawe, Serjeant-at-Law, who is appointed President of this Court, should be called by the Name and have the Title of LORD PRESIDENT, and that as well without as within the said Court, during the Commission and Sitting of the said Court: against which Title he pressed much to be heard to offer his Exceptions, but was therein over-ruled by the Court." From this date onwards Bradshawe presided at every meeting of the Commissioners held either privately or publicly, and on the 27th January he was to pronounce the sentence of the Court on King Charles. Tradition has it that the warrant for the King's execution was signed in Bradshawe's house at Walton-on-Thames - his own signature, of course, appearing first on that well known document. By bringing his Sovereign to the block, he may be said to have fulfilled the prediction of his early youth, for he certainly had done that which all the world would wonder at!

A scan of a print of a postcard of a facsimile of the Warrant to execute King Charles I.

First signature is John Bradshawe of Marple Hall.

Wealth and honours after Charles I's death

Wealth and honours were literally showered upon Bradshawe after King Charles's death and in February 1649 he was made President of the Council of State, the highest office in the kingdom. In March of the same year he was appointed Chief Justice of Wales and in July he was re-appointed Chief Justice of Chester. During this time he also presided over the newly-constituted Court for the trial of political offenders. Shortly after he was made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, an appointment that was renewed by Act of Parliament each year, and an office he held until February 1656.

The financial and material rewards were enormous. Bradshawe was given the Deanery House at Westminster as a residence to him and his heirs and a sum of £5,000 (£375,000 in today's terms) allowed "to procure an equipage suitable to his new sphere of life, and such as the dignity of his office demanded." In June 1949 he was voted the sum of £1,000 by Parliament (£75,000) but this was referred to a committee to consider how it could be increased. In July a Bill passed through Parliament settling £2,000 (£150,000) a year, "as an inheritance upon him and his heirs forever." Just nine days later the committee mentioned earlier raised the initial sum granted to £2,000 per annum, utilising the sequestered estates of the Earl of St. Albans at Somerhill, in Kent and those of Lord Cottingon at Fonthill, in Wiltshire. This income, equating to approximately £300,000 per annum in today's terms, was in addition to the many other sources Bradshawe must have already established during his long and successful career.

Bradshawe acted as President of the Council of State for the next three years and so far his success had been uninterrupted. As the supreme magistrate his power and influence was second only to Cromwell himself and his authority was almost absolute. The speed with which he had attained power made him a formidable competitor and even a potential rival to Cromwell, with whom he appears to have had a close friendship. It was his boldness and unflinching adherence to principles which brought about his own undoing when an incident occurred which would forever alienate the pair.

Bradshawe falls foul of Cromwell

In April 1653 Cromwell, now intent on government by a single person, dissolved Parliament by force, expelling the members and ordering the doors of the House to be locked. Bradshawe refused to submit in silence to such a daring infringement of Parliamentary liberties and resolved to take his place as head of the Council of State that afternoon. The Lord General was not to be so easily diverted from his purpose and expelled the Council and its members in the same manner that he had dismissed the Commons. Addressing Bradshawe and those assembled with him, he said, –

In April 1653 Cromwell, now intent on government by a single person, dissolved Parliament by force, expelling the members and ordering the doors of the House to be locked. Bradshawe refused to submit in silence to such a daring infringement of Parliamentary liberties and resolved to take his place as head of the Council of State that afternoon. The Lord General was not to be so easily diverted from his purpose and expelled the Council and its members in the same manner that he had dismissed the Commons. Addressing Bradshawe and those assembled with him, he said, –

"Gentlemen, if you are met here as private persons, you shall not be disturbed; but if as a Council of State, this is no place for you; and, since you cannot but know what was done at the House in the morning, so take notice that the Parliament is dissolved."

He was stoutly resisted by Bradshawe, who replied with these memorable words, -

"Sir, we have heard what you did at the House in the morning, and before many hours all England shall hear it; but, Sir, you are mistaken to think that the Parliament is dissolved, for no power under heaven can dissolve them but themselves; therefore take you notice of that."

As a result of this stern uprightness he incurred the enmity of Cromwell, who could not allow his authority to be so openly disputed by the President of the Council. It therefore became necessary to his plans that Bradshawe's power be reduced and in September 1653 he was named as a member of the interim Council of State that was to meet prior to a settlement of a new Government, however, he was no longer permitted to occupy an office of actual power and authority.

In December 1653 Cromwell was inaugurated Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. Bradshawe, ever the Republican, retained the courage of his convictions and remained opposed to unlimited power, whether exercised by the King or by the Protector. In the first Parliament of the Protectorate he sat as a member for Chester and, with others, opposed the authority of his former friend and patron. This was for a brief period only as Cromwell surrounded the House with his guards, administered a corrective in the form of a declaration promising allegiance to himself which he required every member to sign and shortly after dismissed them unceremoniously to their homes.

It was at this time that Bradshawe demonstrated his resolute opposition to the iron-willed Protector, which resulted in much admiration from his fellows. It is recorded that, "when Cromwell appeared desirous of concentrating in himself an arbitrary power, Bradshawe fearlessly and openly withstood him, proclaiming 'if they were to be governed by a single person, Charles Stuart was as proper a gentleman for it as any in the kingdom.'" The scene when this occurred is described as a most illustrious situation for Bradshawe. "Cromwell was backed by all his guards. Bradshawe appeared before him in the simple robe of his integrity. A few words, a brief and concentrated remonstrance were enough. They were uttered, and Cromwell ventured no reply. Abashed the tyrant stood."

For a year and nine months England was left without a Parliament, the supreme power being exercised by the Protector. Everyone holding office was required to take out a commission but this Bradshawe refused to do and carried on his duties as Chief Justice of Chester, offering to submit to a verdict by jury as to whether he had carried himself with the integrity that his commission required. No attempt was made to hinder him although, as might be expected, his daring and firmness provoked the further anger of Cromwell.

For a year and nine months England was left without a Parliament, the supreme power being exercised by the Protector. Everyone holding office was required to take out a commission but this Bradshawe refused to do and carried on his duties as Chief Justice of Chester, offering to submit to a verdict by jury as to whether he had carried himself with the integrity that his commission required. No attempt was made to hinder him although, as might be expected, his daring and firmness provoked the further anger of Cromwell.

Bradshawe succeeded in securing his election as MP for Chester in September 1656, in spite of Cromwell's open opposition, but due to a double return neither representative took his seat. Cromwell had effectively achieved his aim to keep Bradshawe out of Parliament. In 1656 he also sought to deprive him of the office of Chief Justice of Cheshire, but was unsuccessful in this.

After the death of the Protector on 3rd September 1658 he was succeeded by his son Richard Cromwell, a much weaker and less resolute character. On Richard's ascension a new Parliament was called and Bradshawe was again elected member for Chester. Although he took the oath of fidelity to the new Protector, he nevertheless entered into active opposition to the Government with other Republicans and this Parliament came to an end in April 1659. It is around this time that the first indications of Bradshawe's failing health are reported.

Buried in Westminster Abbey but not for long

Six days after Parliament was restored, in May 1659, a new Council of State was appointed and Bradshawe once again obtained a seat and was elected President. In June 1659 he was also appointed a Commissioner of the Great Seal but was subsequently forced, by his failing health, to ask to be relieved of the duties of that office. Bradshawe's last public appearance was when he uttered a strong protest against the action of the army in dissolving Parliament by force in September 1659. Very shortly after this he died, on 31st October, at nearly 57 years of age.

He was interred with much pomp and ceremony in the Sanctuary of Kings at Westminster Abbey, on the 22nd November 1659. It is said that shortly before his death he declared that he did not repent of his conduct towards his Sovereign and that "if the King were to be tried again, he would be the first man to do it."

After the Restoration of Charles II Bradshawe's body, with those of several others, was exhumed from Westminster Abbey by order of the Council of State and on the 30th January 1661, the anniversary of the execution of Charles I, the bodies of Cromwell, Ireton and Bradshawe were hung on the gallows at Tyburn. Their heads were afterwards cut off and set up in Westminster Hall and their bodies burned and thrown into a hole dug under the gallows. It is said that the heads of Cromwell and Bradshawe were still fixed on the spikes of Westminster in 1684, when that of another traitor was placed between them. Now the blue plaque on the side of Marple Co-Op is the only known public tribute to Marple's most famous son.

After the Restoration of Charles II Bradshawe's body, with those of several others, was exhumed from Westminster Abbey by order of the Council of State and on the 30th January 1661, the anniversary of the execution of Charles I, the bodies of Cromwell, Ireton and Bradshawe were hung on the gallows at Tyburn. Their heads were afterwards cut off and set up in Westminster Hall and their bodies burned and thrown into a hole dug under the gallows. It is said that the heads of Cromwell and Bradshawe were still fixed on the spikes of Westminster in 1684, when that of another traitor was placed between them. Now the blue plaque on the side of Marple Co-Op is the only known public tribute to Marple's most famous son.

Bradshawe was married, early in life, to Mary, only daughter of John Marbury of Marbury. She died some years before him and they had no children. She was buried in Westminster Abbey and was amongst those exhumed after the Restoration and re-interred in the churchyard of the Abbey. The exact date of her death is not known.

Bradshawe's supporters and detractors

Bradshawe had as many supporters as he had detractors. The poet John Milton (a cousin of the Judge) said of him:

"He brought to the study of the law, a capacity enlightened, a lofty spirit and spotless manners obnoxious to none, so that he filled the high and lofty office, rendered the more dangerous by the threats and daggers of private assassins, with a firmness, a gravity, a dignity and presence of mind, as if he had been designed and created by the Deity expressly for this work, for how much more is it just and majestic to try a tyrant than to slay him untried?"

This extravagant claim is countered immediately by a no less distinguished authority, the great Clarendon, who describes Bradshawe as:

"A lawyer of Gray's Inn, not much known at Westminster Hall, though of good practice in his chambers. He was a gentleman of an ancient family in Cheshire and Lancashire, but of a fortune of his own making. He was not without parts, and of great insolence and ambition. With great humility he accepted the office - Lord President of the Council - which he administered with all pride, insolence, and superciliousness imaginable."

Other tributes for and against can be found in almost equal measure, but in spite of all his detractors may level at him, one can excuse a great deal when a man stands throughout a life-time firm and true to the principles and the cause which in his heart he believes the best. And if anything further were needed to be advanced in favour of the Judge, the words of Cromwell, uttered after their first clash, should suffice, -

"I have dissolved the Council of State." He said to Desbrough, "in spite of honest John Bradshawe, the President."