I. The Dawn of the Railway Age. 1794-1845

1. The Earliest Railways in the District (1794-1830)

The origins of the earliest railways of the district are inextricably bound up with the preceding canal era, and the need to improve transport facilities between Sheffield and Manchester, which as manufacturing centres grew enormously in the early 19th Century.

The Peak Forest Canal was incorporated in 1794 to run from Ashton via Marple to Bugsworth and Whaley Bridge, with Samuel Oldknow a leading promoter of the scheme. The main part of the canal was opened in 1796, the exception being the Marple flight of locks, and the Aqueduct over the Goyt, which were not completed until 1800 and 1804 respectively. In the interim, an inclined plane tramway, with horse traction, ran from the base of the Lime Kilns at Top Lock to join the end of the canal from Ashton. This was to take materials to the site of work, and to allow traffic to pass between the separate portions of the canal. I hesitate to say this was the first railway in Marple, as there were probably earlier crude tramways at the numerous small collieries of the district, but it was certainly the first of length and any more than local significance. The immediate aim of the Peak Forest Canal was to carry limestone from the Peak District. To gain access to supplies beyond the easy reach of canals due to the hilly terrain, the Peak Forest Tramway was constructed and opened up in sections 1796-1800. The Tramway ran from Bugsworth via Chapel-en-le-Frith to the various quarries at Peak Forest. The need was however felt for better communication between Sheffield and Manchester, than was provided by either canal or road at the time. Various schemes were proposed in 1813 and again in 1824 and 1826 to link the two cities by an extension of the Peak Forest Canal from Bugsworth, by various combinations of canals and inclined plane railways. In 1825 the Cromford and High Peak Railway was authorised to link the Peak Forest Canal at Whaley Bridge with the Cromford Canal at Cromford Wharf, and thus link Manchester to the East Midlands. It was opened in 1830-1, a standard gauge (4'8½") line, like the Liverpool and Manchester, and most British railways since. To pass through the uncompromising terrain of the High Peak, long inclined planes worked by stationary steam engines, and sharp curves were employed. Despite these problems, and those of transhipping goods to and from canal at either end, this railway gave great advantages in the transport of goods over the horse and cart. The white lines superimposed on the photograph above show where the tramway rails used to cross the canal, just below lock 10 (M.Whittaker).

A vintage image of Marple Wharf: Junction of Peak Forest and Macclesfield Canals

This combined with the opening in 1826 of the Macclesfield Canal from Marple Top Lock to the Trent and Mersey Canal near Kidsgrove, forming the most direct route from Manchester to the West Midlands and London, placed Marple on a series of important through routes by canal and tramway for the carriage of goods: most passengers however still went by road, on foot, horseback or coach. The coming of the canal helped continue the prosperity brought by the Industrial Revolution, and particularly Samuel Oldknow's Mills, and has left its mark on the district; the canal was Marple's economic lifeline until the arrival of the railways in the 60's. These canals, and both the Peak Forest Tramway and Cromford and High Peak Railway figure again in the railway political battles of the 40s, 50s and 60s.

2. Some Might-Have-Beens (1830-36)

There was however still no direct route from Manchester to Sheffield. The impending opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway however stimulated the promotion in 1830 of a railway to extend right the way between the two cities. George Stephenson, "The Father of Railways" was the engineer of this line, though there is some doubt whether he actually surveyed the line, or merely acted in a consultative capacity. Certainly with its numerous inclined planes and heavy gradients, it was a most un-Stephenson-like line. It was to start from a junction in Manchester with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and proceed to Stockport, where it turned east, and ran along the banks of the Goyt, via Marple to Whaley Bridge; in Marple the line was to pass beneath the canals, probably by means of one of the "short tunnels" referred to in plans.

A view of Marple Station on Brabyns Brow, from Marple Local History Society Archives.

To surmount Rushop Edge a lengthy series of inclined planes were required; the line then ran down the Hope Valley, and again by inclined planes over Totley Moor and to Sheffield. The course of the line is remarkably similar to the Midland Railways' much later route from Manchester via Stockport and Marple and the present "Hope Valley Line" to Sheffield, which however used tunnels not inclined planes to conquer the Pennine Range.

The scheme met with considerable opposition from those who looked askance at a so-called trunk route which contained 6½ miles of tunnel and 6 inclined planes. A particular critic was Henry Sanderson, the promoter of the 1826 scheme who in 1831 suggested an alternative route via a Woodhead tunnel, Glossopdale, the Valley of the Etherow past Compstall and Marple, and so to Manchester via Stockport.

Both of these schemes would have placed Marple on a through Sheffield-Manchester trunk route, but it is fortunate that the "Stephenson" scheme with all its inclined planes was not built; it belonged to an earlier, more primitive era of railways, and was more akin to a mineral tramway; the second, Sanderson scheme was very close to the eventual course chosen for the Manchester-Sheffield trunk line; but the route into Manchester via Marple and Stockport was not to be, and the line built took a more direct route via Godley; it is interesting however to briefly speculate what might have happened had the Woodhead route been built via Marple!

3. The Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne, and Manchester Railway(1836-45)

The need still remained however for a route from Manchester to Sheffield; the success of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L. & M.) whose receipts, particularly from passengers, exceeded all expectations, gave added impetus for a Railway linking the two cities, especially one suitable for passengers, which the Stephenson scheme had manifestly not been. In 1836 such a line was promoted and a route via Penistone, a Woodhead Tunnel, Longendale and Ashton decided on, with branches to Glossop and Stalybridge. This was authorised by Parliament in 1837 as the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne, and Manchester Railway (S.A. & M.).

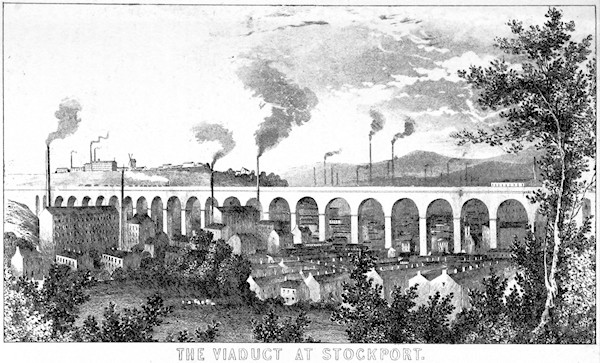

It had been originally intended to have a separate terminus for the S.A. & M. at Store Street in Manchester but it was soon decided, in order to reduce costs, to make a junction with the so called Manchester and Birmingham Railway (M. & B.) at Ardwick and run into a joint terminus at London Road. The M. & B. was authorised in the same year as the S.A. & M. to run from Manchester to the Grand Junction Railway at Crewe; it was opened in 1842, and included the massive Stockport Viaduct.

Stockport Viaduct circa 1854.

But it soon became apparent, even before these lines were constructed, that a great deal of inconvenience was going to be caused by the number of separate terminals in existence or planned in the city - four in all. Accordingly in 1838 the directors of Manchester and Leeds Railway (M. & L.) approached the L. & M. Board and it was agreed to build a line linking the two railways, with a joint station at Hunt's Bank. The L. & M. agreed to this, and work started; the L. & M. however had immediate doubts about the scheme, and proposed to the M. & B. and S.A. & M. that they should jointly build a line from Ordsall Lane, near the L. & M. terminus at Liverpool Road to Store Street, crossing Manchester on a viaduct, with "a great central station for general use at Store Street" and a tunnel connecting with the M. & L. terminus at Oldham Road. Prophetic words, a great central station. But the scheme was not to be, and the hope of having one central Manchester station faded; instead stations proliferated, so that by 1910 Manchester had 7 where trains terminated, if Salford and Mayfield are included; even now there are 3. As it was the M. & L., having already started building the Hunts Bank link, frightened the L. & M. into keeping to its original arrangement, by threatening to ally with the Old River Company and thus gain independent, albeit watery, access to Liverpool. Accordingly in 1844 the Hunts Bank station opened, and was named Victoria.

Crowds await a royal visit at Manchester Victoria in 1905

A link between L. & M. and Store Street was eventually built and opened in 1849 - the Manchester South Junction (and Altrincham) Railway (M.S.J.A.) - the Altrincham branch was an afterthought; but this was too late, and henceforth the railways of Manchester were irrevocably split into North and South halves. The line eventually built to Marple, being a branch off the successor of the S.A. & M. was therefore inevitably a southern Manchester line. This split continues to the present day, and if anything is more marked than ever. However by 1841, the first section of the SA. & M. was ready, albeit only single track, and trains began running from the temporary M. & B. terminus at Travis Street in Manchester to "Godley Toll Bar" near where Godley Junction now is. There were stations at Fairfield, Ashton, Hooley Hill (renamed Guide Bridge in 1845), Dukinfield Dog Lane (closed in 1845; it was about ½m east of Guide Bridge near where the line crosses the Peak Forest Canal), Newton and Hyde, and Godley Toll Bar. In 1842 the line was extended to "Glossop" (now Dinting) with an intermediate station at Broadbottom; in the same year the new joint terminus with the M. & B. was opened at Store Street, later known as London Road, and stations were opened at Ardwick and Gorton.

Ashburys did not open until 1855. Sheffield was finally linked with Manchester to the strains of "See the Conquering Hero Comes" from the band accompanying the first through train in 1845.

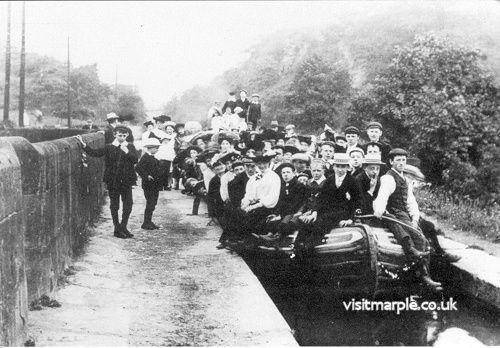

Meanwhile the S.A. & M. had already arranged for horse drawn omnibus feeder services to Ashton and in 1842 Mr. James Boulton (see note below) went into business providing horse drawn passenger boat connections by canal. Early in 1843 he started a service from Dukinfield Dog Lane Station along the Peak Forest and Macclesfield Canals to Marple and Macclesfield. To provide this service he bought 6 or 7 disused boats from the Glasgow and Paisley Canal; each accommodated 100 passengers, and travelled at 8 to 10 m.p.h.

A packet boat trip crossing Marple Aqueduct some time in the late 19th century.

The boats were drawn by 2 horses, on one of which rode a postillion in buckskin trousers. Fares charged were 1½d per mile "cabin" and 1d per mile "steerage", with 60 lbs of luggage per person free. Boulton received 3d from the S.A. & M. for every passenger coming off his boats who bought a full ticket to Manchester. While progress must have been rapid on the level sections of the canal, going up the flight of 16 locks at Marple must have been painfully slow. No doubt many got out to walk, refreshing themselves en route at the Aqueduct, Navigation and Ring '0' Bells public houses. It is not known how long this service lasted: It probably ceased when the Stockport-Macclesfield line opened in 1845, but it marks the first extension of rail based transport interests into Marple, the prelude to the arrival of the railway proper.

Note: Although the original book "Railways of Marple and District From 1794" states that James Boulton set up the packet boat business, it is believed that this was actually John Boulton.