X. The Beeching Era 1962-1970

1. The Beeching Report

Despite the effects of the Modernisation Plan, and the piecemeal closures of grossly uneconomic lines in the 50's, B.R.'s losses continued to mount, so that by 1962 the annual deficit had reached £104m - a fantastic sum then. The Government therefore appointed as Chairman of the newly formed British Railways Board (which replaced the old British Transport Commission and Railway Executive), a certain Dr. Beeching, to review the state of B.R. In 1963 appeared the results of his review in a Government document entitled "The Reshaping of British Railways", usually known as the "Beeching Report".

New and old steam locomotives meet at Marple Wharf Junction in August 1956. An Up train of coal empties is hauled by a wartime "Austerity" 8F 2.8.0, while a pre first world war L.N.W. "Bowen-Cooke" Class 7F.0.8.0 No 49093 stands at the Home signal. Note the fine Midland Railway lower quadrant signals (E.Oldham). (From Marple Rail Trails)

Much of what was contained in the report was very true: that many of the lesser used lines and stations, passenger and freight, ran at such a loss as to completely submerge the profitability of the busier lines; that the railways had for too long in the face of road competition concentrated on small freight consignments instead of the large, heavy flows to which they were well suited; and that many suburban lines were an expensive luxury, as they were only busy for two or three hours of the day. The remedy was therefore simple - close all the unprofitable stations and routes, concentrate on heavy Inter-City passenger and bulk freight movements, and make the commuter pay the real costs of his peak hour services. In our area the Beeching Report advocated the closure of the Hayfield and Macclesfield branches, the Hyde loop, the Midland route from Central to Chinley via Cheadle Heath, the Buxton L.N.W. line, the Midland Buxton branch, the Hope Valley, and all stopping services between Manchester and Derby. The idea seems to have been that a Manchester-Derby semi-fast service should continue to serve Belle Vue, Reddish, Bredbury, Romiley, Marple, New Mills and Chinley, but all other stations in the area were to close. Later proposals went even further, and the only line not threatened with total closure was the electrified Main line from Piccadilly to Euston via Crewe and Macclesfield.

As may be expected, this Report produced a terrific outcry of protest, and Beeching was dubbed the "Axe-Man". There was a great deal of truth in what Dr. Beeching said but the remedies he suggested were too severe. There was much talk of "pruning", but the danger was that the indiscriminate lopping of branches might lead to the death of the trunk; or in another metaphor, that if too many tributaries were stopped, the river might dry up. Dr. Beeching and the whole British Railways Board dismissed too much traffic and too many lines as hopeless cases: the Axe was excessively Draconian. What the report also ignored was that there was a growing feeling throughout the country that the running of rail services in many rural and suburban areas should be regarded as a "social service" like as a hospital, and not expected to run at a profit; the Government should subsidise lines and not shut them down. This was not however officially recognised until the 1968 Transport Act, which set up the system of Government grant aid for socially necessary loss-making lines.

Before however any line could be closed, the Transport Users Consultative Committee (T.U.C.C.) set up under Nationalisation in 1947 as an early consumers' protection body, had to hold a public hearing to assess the hardship that would be caused by the closure of a line, and report to the Minister of Transport; he would then decide whether the line should close or not. When therefore notices were posted late in 1963 that all services were to be withdrawn from Buxton - from both Millers Dale and Stockport, the T.U.C.C. was deluged with protests. Buxton was an unfortunate choice for a test case, as the objectors had a very good case; not least that the roads to Buxton were often cut off by snow in winter, while it was plain that the A6 road was already overcrowded. After a long and bitter campaign, in the end even the anti-rail Minister of Transport, Mr. Marples, was forced to refuse his consent to closure. Several subsequent attempts were made to close the line, including a crackpot scheme put forward in 1973 to convert the track-bed beyond Hazel Grove into a bus-way; but all had been defeated, and now the line's future seems assured.

2. The End of the Midland Main Line

Throughout the 60's private car ownership rocketed and usage of lines dropped, under the impression that "they'll all close soon anyway". In 1966, accompanying another attempt to close the Buxton L.N.W. line, B.R. put up for closure the Millers Dale to Buxton Branch, along with all stopping services between Manchester and Derby via Marple, Chinley and Matlock. Again a great fight was put up, and while the Buxton L.N.W. line was saved, the Minister of Transport, Barbara Castle, approved the rest for closure.

Marple Station on 2 August 1969.

Closure took place in two stages; 2nd January 1967 saw the official closure of Cheadle Heath Station, Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Didsbury and Stockport Tiviot Dale Stations, along with the "Marple Curve" near Romiley, thus finally depriving Marple of links with Stockport and Manchester Central via the South District Line; these trains were the last regular steam-hauled passenger trains to call at Marple, though steam-hauled goods trains continued to pass through almost up to the very end of steam in August 1968. Two months later in March 1967, stopping services between Chinley and Matlock were withdrawn, along with the Millers Dale-Buxton Branch service. Main Line services however continued to run from Central to Nottingham and St. Pancras via the South District Line, and Disley Tunnel.

At the same time a new service was put on from Sheffield Midland to Manchester Piccadilly to replace the old Central service; there were 5 Up and 4 Down trains each day, formed by d.m.u.'s. They called at all stations from Sheffield to Chinley via the Hope Valley, then New Mills, Marple and Romiley only to Piccadilly. There were also a couple of trains each way between Piccadilly and Chinley only via Marple, giving Marple 7 Up and 5 Down Midland line services; all connected at Chinley with Main line trains, and gave Marple a better Sheffield service than since the opening of the "New Line" and extra fast services to and from Piccadilly.

But the Midland Main line into Manchester was fast disappearing, as it had lost its raison d'être when the L.N.W. route was electrified. From 1st January 1968 most of the remaining Midland line services were transferred back from Central to Piccadilly, thus reversing the Midland's move from London Road to Central of 1880. The remaining trains continued to call at Chinley to connect with the Piccadilly-Marple-Sheffield services. A few peculiar late night and seasonal trains continued to run via the "New Line" in and out of Central, and one very peculiar Sunday train ran each way between Liverpool Lime Street and Sheffield via Manchester Central and Guide Bridge, and so to Marple, where the train called, and Sheffield. This was in fact the last service between Marple and Central, though it only ran once a week! The service, which began in the mid 60's, also strangely revived a Marple-Liverpool service, last seen in 1939. In April 1968 the Chinley-Matlock link closed completely; the Matlock-Derby portion remained open as a branch line, while the Chinley-Peak Forest-Buxton section remained open to freight traffic. But the great Midland Main line through the Peak, which had arisen out of such intrigue, and taken so many years, and so much capital and labour to construct, was closed for the most part in a day. The Midland line services shifted route once again to run from Piccadilly via Marple to Chinley and now via the Hope Valley and the Dore South Curve to Chesterfield and Derby, a route much better graded, and not much longer than via Matlock, and which had been used by occasional St. Pancras-Manchester services in Midland days. Chinley was also now no longer a junction though it remained a Main line calling point for another four years yet. May 1969 saw the demise of Manchester Central, 90 years after first opening; its remaining services were transferred to Oxford Road and Piccadilly, including the peculiar Sheffield-Liverpool Sunday service, which continued to call at Marple. The South District line was quickly lifted, and remains a disused, rubbish strewn strip of land for much of its length to this day. The "New Line" however remained open, as it was -and is, a valuable freight link between the limestone quarries of the Peak and the I.C.I. Works on the Cheshire Plain. And so the wheel came full circle, when once again all Midland trains ran into Manchester London Road (renamed Piccadilly) via the Marple and Reddish route, as they had done prior to the opening of Central in 1880 - except that they no longer deigned to call at Marple. Central has been left to brood over its past glories, like some prone giant; no new purpose has been found for its train shed, unless you count its present use as a car park, most unsuited to its status as a listed structure of exceptional importance.

The Twilight of Steam. "Black Five" 45073 pounds through Marple Wharf Junction on an evening Sheffield Midland-Manchester Central local in March 1966. (JR. Hillier)

In these Beeching days no line seemed safe from closure: in January 1970 the old Great Central Main Line from Manchester to Sheffield Victoria, only electrified 16 years before, lost its passenger service, though local services continued to run to Glossop and Hadfield. Thereupon a fast service was put on between Piccadilly and Sheffield, via Reddish, Marple and the Hope Valley, all of them non-stop. All were formed of d.m.u.'s except the "Harwich Boat Train" which ran daily each way between Manchester Piccadilly and Harwich Parkeston Quay to connect with Continental boat sailings. This train was diesel-hauled, usually a Class 45 or 46, with a long rake of Main Line coaches, and usually a pre-War Gresley buffet car, at least until 1976.

Thus between 1968 and 1970 the Hope Valley Line, built so late, and for so many years a purely local line, had greatness thrust upon it as it replaced the older pioneering lines to North and South of it as the main passenger link from Manchester across the Southern Pennines to Sheffield or the Midlands. And if, as seems likely at the time of writing, the Woodhead Route closes for all traffic, the Hope Valley may end up as the only link.

The interior of Marple Wharf Junction Signalbox shortly before closure in July 1980. (From Marple Rail Trails)

The interior of Marple Wharf Junction Signalbox shortly before closure in July 1980. (From Marple Rail Trails)

As a result of these changes, the Manchester-Marple-Sheffield semi-fast trains were cut-back to ply between Sheffield and New Mills, where they could connect with the local services via Marple to Manchester. The remaining Midland Main Line services to Nottingham and St. Pancras continued to make a ritual stop at Chinley, out of habit rather than anything else, as they rarely connected with anything - all the lines which had made Chinley so important a junction had closed, and only the couple of Hope Valley locals terminating at Chinley connected with anything Main Line.

Chinley's end was nigh, and came in May 1972, when the remaining Midland Line services were further cut down to only two trains each way daily between Manchester and St. Pancras, now virtually a stopping service, taking about 4½ hours (compared with 3 hours 35 minutes in 1904); in addition they ceased to call at Chinley, which was thus left almost entirely without Main Line trains - the few trains now remaining called at New Mills. At the same time alternate Manchester-Sheffield expresses began stopping at New Mills to connect with the Hope Valley locals. Some of the Sheffield expresses were also extended East of Sheffield to destinations such as Doncaster, Hull and Cleethorpes.

And thus in 1972 New Mills finally supplanted Chinley as the connectional king-pin of the remaining Midland line services in the North West, as Chinley had once supplanted Marple. Chinley Station, now largely flattened, and reduced from 6 to 2 platforms, thus reverted to its pre-1902 status as a wayside halt. New Mills by contrast is a relative hive of activity, mainly due to the constricted layout, which makes its necessary to shunt terminating locals from Manchester or Sheffield into a siding or the Hayfield line tunnel to make way for through trains; but it is hardly as busy as Marple or Chinley in their respective heydays.

The remaining St. Pancras services gradually disappeared as they were poorly patronised, and very poorly publicised. In May 1976, they were down to one each way daily, and in May 1977 the last Up and Down trains were withdrawn altogether - except on Sundays, when for some reason two services continued to operate each way, reversing at Sheffield. The only remaining regular loco-hauled express train left passing through Marple is thus the "Harwich Boat Train" which of course does not stop.

Marple Station. LMS Black Five 4-6-0 no. 45073. This train is the Liverpool to Harwich boat train, steam hauled from Manchester to Sheffield.

And so in just over 10 years the Midland line services into Manchester have been reduced almost to nothing and the great Midland terminal of Central closed, while the Hope Valley and Marple route remains the sole link to escape closure. In retrospect, though the closure of Central was regrettable it was probably a beneficial move, as it reduced the excessive number of major termini in Manchester, thus eliminating many cross-city jaunts for passengers. The South District line should not have closed, as with dieselisation, a regular service, and publicity it would have been a busy suburban line today. The demise of the Manchester-St. Pancras service is a pity, but with the Euston electrification, it was no use as a through service. But the loss of a decent service between Manchester and the East Midlands has left a large gap in the railway network. The closure of the Chinley-Matlock section of the Midland line through the Peak was also a grave mistake, with the inadequate roads choked with tourists and heavy lorry traffic - even B.R. regret the closure as freight from the limestone quarries of the Buxton area has to detour via Chinley and Sheffield to reach the South. But even now there are moves afoot to re-open the line as a serious private preservation venture under the aegis of the Peak Railway Society, 'the aim being to operate a regular passenger and freight service as well as steam trains'. The closure of Woodhead to passengers, and concentration on the Hope Valley route was regrettable, but in the circumstances, probably the best of a bad job - the Hope Valley route had to be retained anyway for its freight traffic and because permission to withdraw local services had several times been refused. What is more closure of the Woodhead route allowed concentration of services via Sheffield at the Midland Station, thus giving much improved cross-country connections. The choice of New Mills instead of Marple as the lynch-pin of the remainder of the Midland line services was a strange one, but dictated by the fact that by 1972 only New Mills had stabling sidings for terminating trains, though other facilities at New Mills, particularly car parking, are much inferior to Marple. The increasingly suburban nature of the services to Marple, and on the whole line, was further shown when in 1968 through ticketing facilities were withdrawn from all stations as an economy measure; tickets henceforth could only be bought for stations directly served from the station in the case of Marple, stations Manchester to Sheffield inclusive: before it had been possible to book a ticket to almost anywhere in Great Britain, calculating the fare on mileage.

And thus the drastic cuts of the Beeching era, some justified, some in retrospect very regrettable, dismantled much of the once proud Midland system in the North West, and undid the work of the mid-19th Century Railway Politicians. Marple in the process had lost almost every Main Line connection and become a purely suburban station - a process however which really began in 1902, when it was by-passed by the opening of the "New Line". The net result has however been to make the Marple and Hope Valley route more important than before, as it is now the only Main Line route across the Southern Pennines.

3. Freight Closures

While most lines in the district have remained open for freight traffic, the closure of goods stations has been almost total. The implementation of this part of the Beeching plan has been very thorough, and gone almost completely unnoticed, overshadowed by the more glamorous fights to save passenger lines. Within three years of the Beeching Report almost every goods depot in our area had closed down. Strines went first in August 1963, followed by Marple on 5th October 1964. With the closure of the goods yard, the track was promptly lifted; with the reduced services of the 1960's and the universal use of d.m.u.'s, the Up loop and Down bay were no longer required, and were also removed; Marple was thus reduced to plain Up and Down lines with a crossover at the Southern end to enable terminating trains to turn back. The wooden goods shed was demolished soon after, and the former goods yard became an unofficial car park for rail users.

The demolition of Marple goods shed after closure to freight on 5th October, 1964. Note the massive timbers of this shed, constructed in c. 1875. The site is now occupied by the car park.

Rose Hill Goods Yard did not last much longer, and in March 1965 the last coal train left behind a Stanier 2-8-0 8F, the last steam train to call at Rose Hill. Bowden's the Coal Merchants maintained their business in Rose Hill Yard, receiving road-borne supplies from a coal concentration depot set up at Woodley, until this too closed in 1972; now coal has to come by road from Stockport or Ardwick West in Manchester. General merchandise continued to be dealt with at New Mills East until 1968, when that too closed, and business transferred to Stockport (Edgeley); this in its turn closed in 1972, and any goods coming by rail now have to be delivered by road from Ardwick West.

At the same time parcels collection and delivery ceased when freight facilities were withdrawn, though parcels could still be consigned or collected by the public at the station. Now only Marple retains this facility in our district.

And so the freight traffic dealt with at all such smaller goods depots was thrown onto the roads; to be fair, however, this was hardly B.R.'s fault, as the traffic lost was on the whole uneconomic in the face of road competition with its hidden subsidies, and the Government was adamant the Railways must pay their way. It is a pity however that a least one coal depot was not allowed to remain open in the Marple area, and one goods depot in the Stockport district to keep at least some traffic off the roads.

4. The Closure of the Hayfield and Macclesfield Lines

Every line and every station in the district was threatened in the 1960's. The Manchester-Marple-Hayfield and Macclesfield services were obvious targets, as they were heavy loss makers; in 1968, which saw the start of the system of grant-aid to be paid by the Government to cover losses incurred on lines it was deemed socially desirable to keep open, these services required a subsidy of £344,000 p.a., and this figure continued to rise. In 1966 B.R. therefore published proposals to withdraw all services between Manchester and Hayfield and Macclesfield, thus going further than even the Beeching report. This proposal was however turned down by the then Minister of Transport Barbara Castle, at least in so far as it related to the main line section between Piccadilly and New Mills because of its heavy use by commuters. She accepted however there was a case for the examination of the Macclesfield and Hayfield branches, and agreed to the re-publication of these parts of the proposals. This is what B.R. did, and early in 1967 closure notices were posted for the New Mills-Hayfield and Marple Wharf-Macclesfield sections of line. T.U.C.C. public enquiries were held in March 1967 at Macclesfield and Hayfield. Many objections were raised, especially to the closure of the Macclesfield line, which would cut off any direct access between Marple and Macclesfield, as no alternative road service was feasible: in particular schoolboys travelling to the Kings School, Macclesfield would have no alternative public transport. While there were objections from the places, such as Higher Poynton, on the line, Macclesfield itself showed little interest; but the strongest protests came from Marple, where there was of course a very heavy commuter usage at Rose Hill. I myself was an objector to the closure, being a regular traveller between Rose Hill and Belle Vue, en route to Manchester Grammar School.

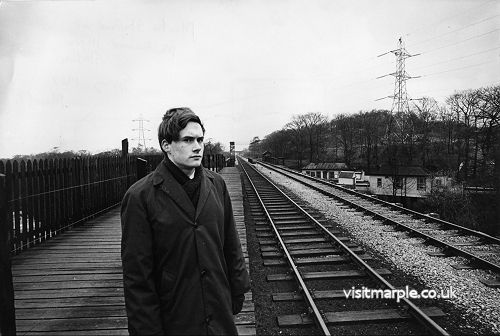

Martin Stafford, who campaigned to stop the closure of the Macclesfield to Rose Hill Line, at Middlewood Higher Station in the summer of 1966.

The outcome rested with the Minister for over two years after the enquiry, until on 12th June 1969 the Minister announced that the Hayfield and Macclesfield Lines had to close, but that the Marple Wharf Junction-Rose Hill Section was to be spared. Evidently the strength of objections from Marple, with its vociferous Council and local organisations, must have impressed the Minister, so that Marple is left in the enviable position, in these post-Beeching days, of having two stations only a mile apart, one on the Main Line, the other on a branch terminating on the other side of the town; a generous provision, unparalleled now outside London. The salvation of Rose Hill was undoubtedly its commuter traffic, which would have transferred to the already congested roads, if the station had closed.

Events now moved quickly and the axe was inescapable, despite last minute pleas from Local Councils and M.P's to B.R., the Minister, and S.E.L.N.E.C. (the Passenger Transport Executive or P.T.E. set up under the 1968 Transport Act to control public transport in South East Lancashire and North East Cheshire -S.E.L.N.E.C.). The official date of closure was Monday, 5th January 1970, and on the preceding Saturday an enthusiasts' excursion toured the two lines. The last train to run on the Macclesfield Line left Rose Hill late on the Saturday night to the accompaniment of detonators exploding and the glare or camera flashbulbs. The last trains on the Hayfield Branch ran the following day.

The Hayfield Branch was quickly lifted, and left derelict for some years; in 1975 however the station buildings and platform at Hayfield were demolished, and the site flattened to make a car park and bus station. The track-bed however remains in use as the Sett Valley Trail Bridleway; but in New Mills the course of the line has been eradicated by bulldozers and "landscaped" into a footpath. Hayfield is now therefore dependent on buses for public transport, and lacks any through service by bus to Manchester - as sure a way as any to drive people into their cars.

The Macclesfield line however did not acquiesce to closure so easily. Early in 1970 a deputation headed by Dr. Michael Winstanley, Liberal M.P. for the Cheadle constituency, obtained an assurance from B.R. that the Macclesfield line would be left in situ until August to allow for the possibility of S.E.L.N.E.C. deciding to re-open the line. S.E.L.N.E.C. was not however very interested, as they were short of money, and half the line, beyond High Lane, was out of their area anyway.

However in May 1970 a group of railway enthusiasts and other interested people began making an attempt to save the line, and formed the "Lyme Handley Railway Preservation Society" taking their name from the parish of Lyme Handley on the route. Their immediate aim was to prevent B.R. lifting the track, and then raise the £50-i 00,000 necessary to purchase the line and equipment to operate it. The eventual intention was to single the line, and run a regular diesel railcar service from Rose Hill to Macclesfield, with steam-hauled trains for enthusiasts at weekends. They proposed re-opening Middlewood High Level, and if B.R. would not allow them to run into Macclesfield Central, to build a separate station just to the north. The stations en route were to be un-staffed halts with the guard collecting fares; several new halts were also proposed. Much detailed work was done on the feasibility of the scheme, and the valid point made that if B.R. had carried out the proposed economies of singling and un-staffing, closure might have been averted.

The last days of Steam at Marple. The 15.30 Manchester Central-Sheffield Midland pauses at the up platform at Marple in May 1966 behind "Black Five" 45404. At the down a Derby Lightweight d.m.u. is leaving on a Hayfield-Manchester working. Note the derelict goods yard (right) (I. R. Smith)

A public meeting to drum up support was held in Marple Bridge in June 1970, and was attended by Dr. Michael Winstanley, Liberal M.P. for the Cheadle Constituency, as well as Local Councillors, members of the Dinting Railway Centre, and some railwaymen - about 80 in all. There was some enthusiasm for the scheme, but one railwayman, a former driver on the line, said that in the 30 years he had worked on the line, he had seen more trains run empty than full. It was however decided to form a working party to negotiate with B.R. and report back to a public meeting in Hazel Grove in July. The working party certainly did work; they delivered 9,000 leaflets to the area and produced very detailed plans and costings for the re-opening and operation of the line. But at a meeting held with B.R. later in June it transpired that while B.R. was prepared to consider this scheme, and give access to the line for surveying etc., they required an immediate payment of £1,400 as compensation for not lifting the track in August - and this would only buy three months respite. B.R.'s argument was that they were losing interest charges on the capital tied up in the scrap value of the track, but as the scrap value was rising all the time, and the line was not lifted in the event for another six months, this was plainly a red herring. This was however the rock on which the scheme foundered, and though frantic attempts were made to raise the sum required, only about £300 was in hand by the crucial date. So the scheme was forced to fold up. It is possible that if B.R. had been more sympathetic, the scheme might have succeeded, though there would have been formidable difficulties; but now the line has gone for good.

Lifting south of Rose Hill commenced late in 1970, well after the deadline given to the Lyme Handley people, and was completed by March 1971. The station at Higher Poynton was soon demolished, as was that at Bollington, where by 1973 industrial premises had risen on the site of the goods yard and Main line, thus blocking any re-opening. High Lane Station however remained derelict for seven years after closure, until demolished in 1977. The land has been sold to the Local Authorities on the route, and there have been suggestions of using it as a Bridleway, footpath or road. To date however most of the trackbed is quite derelict, though used in places as an unofficial footpath.

The Rose Hill line (at Rose Hill Station) being turned into a single line, taken by R P Smith in July 1980.

At Rose Hill the main buildings on the Up platform were soon demolished, as they were no longer required now the station was a terminus; the station staff was reduced to one man on duty at any one time, with 2 men covering the 17 hours the station was open. A new booking office was provided on the Down platform by refitting the former ladies waiting room, with a ticket window facing the platform; the little lean-to wooden ticket office tacked onto the waiting room then became a store, and has now been removed. The waiting room was redecorated and provided with a gas fire, while electric lighting was installed throughout to supersede gas lamps. Later, in September 1970, the signal box was closed and all signals at the station removed; the branch has thenceforth been worked on a kind of "one-engine in steam" principle, that is only one train is ever allowed on the branch at any one time. Despite this the track remained double, thus giving Rose Hill, quite unnecessarily, separate arrival and departure platforms. This arrangement, originally "temporary", persisted because to single the line would require extensive signalling and trackwork changes at Marple Wharf Junction. For most of the 70's the line through Marple was about to be re-signalled at any time, so the work was put off: the scheme has now just been completed in July 1980. As a result the Rose Hill branch remained double, an interim which lasted 10 years! As a result of the closure of the Hayfield and Macclesfield lines, a revised service was introduced to Rose Hill, Marple and New Mills; at long last Rose Hill, which had barely escaped doom, was given an even-interval hourly service, with most trains via the fastest Reddish route. On the debit side, however, there were fewer trains in the morning peak than before, and early morning and late evening services were withdrawn. The interval service was a great improvement, but the total number of trains remained the same as before - 17 to and 19 from Manchester. The service at Marple, however, went to pieces with the new timetable; instead of a regular half-hourly service, the basis of the off-peak service became a train roughly every two hours each way between New Mills and Manchester (instead of hourly as before) routed the slow way via Guide Bridge. The gaps in this very irregular service were filled by hourly trains turning back at Marple, but again these were not quite regular. There were not many less trains than before: 32 to and 34 from Manchester in 1970, compared with 40 and 42 respectively in 1969, but the interval principle was lost. The whole effect was very messy, and really gave only an hourly service, as compared with half-hourly before, though peak-hour services remained good. At the same time 1st Class accommodation was withdrawn from all services to Rose Hill, Marple and New Mills, as it was little used, and took up valuable space in the rush-hour.

And so in our district, the cold winds of change were blowing, but Marple escaped the Beeching Axe comparatively lightly, losing only its Midland line services, the Macclesfield branch, and one station at High Lane. Many a larger town or city, such as Mansfield, Leigh (Lancs.) or Ripon lost their rail services altogether. Marple was very fortunate to retain two stations, as well as two lesser ones at Middlewood and Strines; in particular the survival of the Rose Hill branch was little short of miraculous, leaving Marple to join the select list of places to escape the Beeching Axe with two stations. The reason for this undoubtedly lies in the large number of peak-hour commuters, the inadequacy of the road system in the area, and not least due to the strength of opposition to the closure put up locally.