II. The Railway Comes to Marple. 1845-1868

1. The Abortive Whaley Bridge Branch (1845-51)

The next fifteen years are a tale of the railway which was coming to Marple, but never actually got there for one reason or another. The year 1845 marked the height of the "Railway Mania", when a multiplicity of competing and needless schemes were proposed; most of them collapsed when the bubble burst in 1846. Two mania schemes were eventually built however, and had a great effect on our district.

The first was the ponderously titled "Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway" (M.B.M. & M.J.), which was to make a line from Cheadle Hulme to Ambergate, and thus provide a route for the M. & B. to Ambergate and so to London independent of the Grand Junction Railway (G.J.R.) with which the M. & B. was in continual dispute. This line would have passed very closely to High Lane and the southern end of Marple.

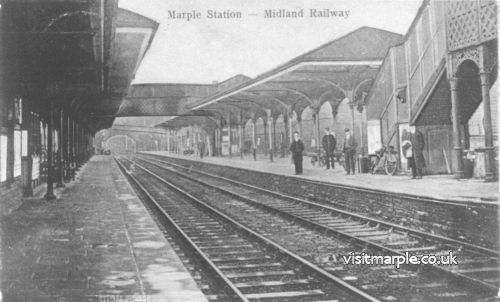

Marple Station in its late 19th century heyday, c 1890, looking towards Manchester. Note that Marple North Signalbox is just visible under the bridge beyond the station, and the "knob up" ground frame cabin serving the goods yard can be seen under the right side of the footbridge linking the two main platforms. (From Marple Rail Trails)

The other line was promoted by the S.A. & M. and was for a line from Hyde Junction via Marple to Whaley Bridge, with a branch to Hayfield; the eventual aim was to reach Buxton and provide an outlet to the Midlands via the C. & H.P. The M.B.M. & M.J. and this branch were obviously therefore in competition in covering much the same ground between Manchester and Buxton, but agreement was reached that neither company would oppose the other. Both were authorised in 1846.

The SA. & M. in 1846 purchased the Ashton, Macclesfield and Peak Forest Canals, along with the Peak Forest Tramway connecting with the latter. This consolidated their grip on these feeders to the railway, prevented any competition from the canals with their proposed Whaley Bridge branch, and "occupying" to the district they passed through, probably with a view to preventing an invasion 'by any other company, notably the London and North Western Railway (L.N.W.) recently formed by the amalgamation of the L. & M., M. & B., Grand Junction and London and Birmingham Railways. Meanwhile the S.A. & M. accepted a tender from Miller and Blackie of £238,515. 18s. 8d. for the construction of the line from Hyde Junction to Whaley Bridge; a ceremonial cutting of the first sod was held, and work began. One of the last acts of the S.A. & M. Board was to accept a tender for rails for the line; for on 1st January 1847 the S.A. & M. amalgamated with various lines in Lincolnshire and became the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (M.S.L.).

Marple Wharf Junction c. 1960-63. LMS 8F 2-8-0 no. 48715. St. Helens - Oakamoor (Staffordshire) sand train, which used the Rose Hill to Macclesfield Central route.

But the mania of 1845 was followed by a slump, and drastic economies were necessary; in November 1848 work on the Whaley Bridge branch was stopped, and in 1851 powers for the line beyond Hyde allowed to lapse and the rails pulled up on that portion which had been finished as far as Hyde, because they were needed elsewhere. Thus Marple, which might have had a railway by 1850 had the finances of the M.S.L. been less shaky, was forced to wait another 15 years to get its line.

2. L.N.W. "Invasion" - The Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway (1854-57)

In the interim the M.S.L. had to countenance an "invasion" of its "territory" when in 1854 the nominally independent Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway (S.D. & W.B.) was authorised; it was in fact an L.N.W. scheme. And it was perfectly obvious that with a railway to Whaley Bridge, the M.S.L.'s interests would suffer; in particular the traffic then passing from the C. & H.P. onto the Peak Forest Canal at Whaley Bridge would pass onto this new line, thus avoiding transhipment, and the M.S.L. would lose its hold on the territory south east of Manchester and its hopes of reaching Buxton. The L.N.W. Chairman, Lord Chandos, blandly assured his counterpart on the M.S.L., Lord Yarborough, that they would protect the canal traffic of the M.S.L., as far as it could, from the competition of the S.D. & W.B. - though there was plainly no intention of honouring this, as events showed. Had finances not been so shaky, there is little doubt that the M.S.L. would have revived their Whaley Bridge branch, linked it with the Peak Forest Tramway, and made an attempt to get to Buxton first and block the L.N.W.'s schemes. This it prepared to do in 1856, when, on the advice of the Midland, it resurrected the Whaley Bridge branch to run from Hyde Junction, via Romiley, Marple and New Mills to Bugsworth; here it was to connect with the Peak Forest Tramway to reach Buxton; there was also to be a Hayfield branch. But the M.S.L. was in no financial position to get to Buxton. What is more the M.S.L. had no wish to break entirely with the L.N.W. which was the only major railway with which it had any physical links.

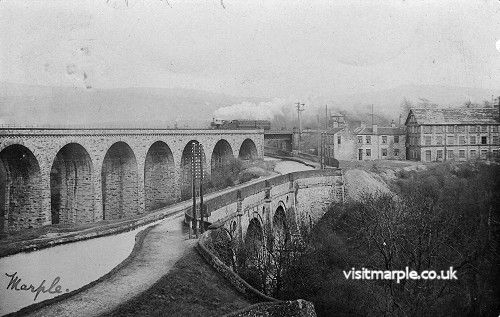

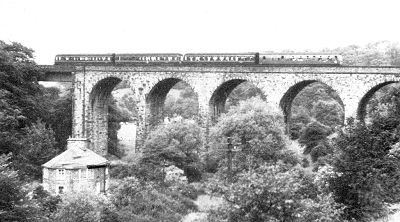

Marple Aqueduct and Viaduct with the Queens Hotel and Aqueduct Mill.

The M.S.L. was therefore unable to do anything to prevent the S.D. & W.B. which opened in 1857, and was thus the first railway to pass through Marple, albeit only the southernmost tip. Soon after a link was made to the C. & H.P. at Whaley Bridge, and this promptly drew off most of the traffic which had previously passed onto the Peak Forest Canal, to the disgust of the M.S.L.

Until 1857 both the Midland Railway and M.S.L. were party with the L.N.W. to an illegal "common purse" arrangement known as the "Euston Square Confederacy" designed to strangle the newly built Great Northern Railway, opened in 1850 from King's Cross to Doncaster. However, the agreement collapsed in 1857 due to double-dealing on the part of the L.N.W. As a result the M.S.L. & G.N. promptly allied themselves to run a service between London King's Cross and Manchester via Retford, thus breaking the L.N.W.'s previous monopoly of all London-Manchester traffic. The L.N.W. was furious and tried to prevent this new service by blocking lines into London Road Station, imprisoning passengers who dared to arrive by G.N. trains from London, and even throwing the M.S.L. Ticket Clerk out of his Booking Office and his tickets after him onto the street!

3. The M.S.L. Reaches "Compstall" (1857-62)

In this new climate, and with improving receipts, the M.S.L. determined to obtain revenge on the L.N.W. and press on into the Peak District.

In 1858 the only part of the Whaley Bridge line which had been completed was opened to passengers from Hyde Junction to Hyde, as a single track branch. In the same year the M.S.L. obtained parliamentary powers to construct a line, following the course of the proposed Whaley Bridge branch, from Hyde, via Woodley and Romiley to "Compstall". This terminus was to be perched high above the Goyt Valley near Marple Aqueduct, and was obviously not intended to be permanent, but rather pointed into the Peak District. A tender of £80,000 was accepted from James Taylor and construction began. Work was rapid and line opened on 5th August 1862.

Marple Station. W.D. Austerity 2-8-0 (possibly no. 90312, a Gorton engine).

At last the railway had reached Marple - or almost. The line was single track, and the stations had only one platform. Romiley's present "down" buildings (i.e. on the Manchester platform) very probably date from the opening of the line or soon after, with the exception of the stair hall which was added in the 1880's. There is no record of what "Compstall" station looked like; it was probably a temporary wooden affair and no traces are now visible, though the hollow on the South side cutting wall just west of the viaduct may represent a trace of its site.

Bradshaw 1862 shows a service of 7 trains each way between Manchester London Road and "Marple" (it is interesting that Compstall was called "Marple" in the timetables as an unpleasant surprise lay in store for anyone who arrived thinking they were at Marple, or Compstall, for that matter, as the station was a long way from either!) There was also one late evening train each way between "Marple" and Guide Bridge only giving a total of 8 each way in all. Two trains each way called at all stations to Manchester, but the rest omitted certain stops. The timings were 45-50 minutes for an all stations train, while the fastest took 35 minutes - not bad for 1862 and hardly much worse than the timings of 1980 for the same route!

4. Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway (1860)

"Whereas the construction of a railway on a point on the authorised Newton and Compstall line of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway at Marple in the County of Chester to New Mills and Hayfield in the County of Derby would be of public and local advantage ...." so ran the formal preamble of Bill for the Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway (M.N.M. & H.J.) laid before Parliament in 1860. The L.N.W. however failed to see the "public and local advantage" of the line, but instead saw this ostensibly local line as a thinly disguised M.S.L. attempt to penetrate districts of which the L.N.W. had come to regard itself as sole proprietor.

The L.N.W. therefore promoted another "local" scheme, the Disley and Hayfield Railway, as a branch off its protégé, the still nominally independent S.D. & W.B.

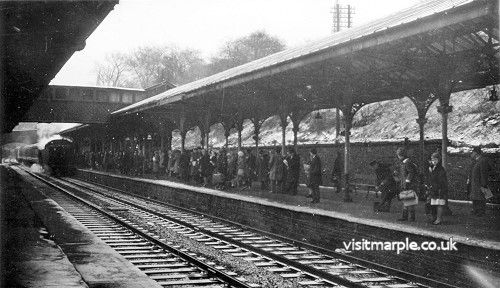

Passengers wait for the 8am from Hayfield on 1st March 1965. From Warwick Burton collection in Marple Local History Society Archives.

Incredibly both Bills were passed by Parliament and construction began on both lines. But public opinion was in favour of the Marple line, and ultimately the Disley and Hayfield line was abandoned - but not before some earthworks had been constructed in the Hayfield Valley. It is as well this line was abandoned, as it would have been ludicrous to have two separate lines serving the small village of Hayfield.

The M.N.M. & H.J. remained an independent railway company for some years yet, and had its own board of directors, though the M.S.L. was well represented on it. It had its own elegant seal with the title of the company, and the arms of Cheshire and Derbyshire inscribed thereon.

Seal of Marple, New Mills & Hayfield Junction Railway (British Railways)

5. Construction of the M.N.M. & H.J. (1861-5)

The engineering works required by the M.N.M. & H.J. were severe, and it must be remembered that all the work was done by pick and shovel, wielded by navvies, with some use of gunpowder to blast rock. Wheelbarrows, horse-drawn carts, primitive hand cranes, and temporary tramways with small contractors steam locomotives were all that were used to shift thousands of tons of earth. The engineer for our line was J.G. Black and the contractors for the Compstall-New Mills section Benton and Woodiwiss, who employed the hundreds of navvies, as well as the more skilled carpenters, stone masons and bricklayers that were required to make a railway line. Most of the men moved about the country, following their contractor to wherever there was work; many came from Ireland, whence they had fled the "hungry forties" of the Irish Potato Famine. They were infamous for their hard drinking, foul language, and vicious brawling; but were also capable of superhuman labours in shifting earth all day in all weathers. Their effect on the life of Marple in the brief period from 1861 to 1865 that they were in the district is not recorded; but it must have reminded residents of the construction of the canals earlier that century, during which a judge, when sentencing 7 persons to death for murders committed in the disorders accompanying the construction of the canal, said he "hoped there were not many more Marples in this kingdom." The navvies building the Woodhead Tunnel not so long before had been considered so degenerate that it was felt necessary to send a missionary to them, and he found them living in mud huts, and willing to sell their wives for a gallon of beer! One hopes that the construction of the M.N.M. & H.J. was not the scene of such depravity; and in fact many navvies and craftsmen settled down in Marple, thus augmenting the Irish Roman Catholic population which similarly arrived with the canals. The large number of old Marple families with Irish names derive from the influx of labour for the construction of canal and railway; this is particularly the case in Marple Bridge, and it is significant that the first Roman Catholic Church in Marple was built in Marple Bridge.

St. Mary's RC Church, Marple Bridge, from Marple Local History Society Archives.

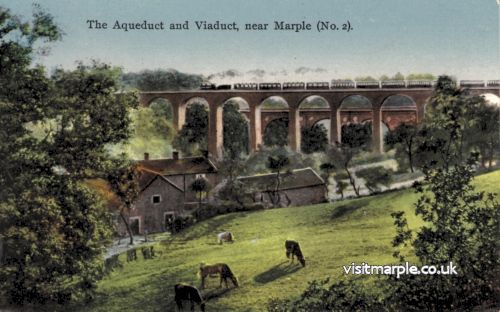

At the northern end of the line was the most impressive structure on the line, Marple Viaduct. On it the line emerges from a broad cutting where once "Compstall" station stood, and strides on the viaduct across the valley of the Goyt, 124 feet in the centre above the river on 12 stone arches, 918 feet long in all; and immediately on gaining the Marple side of the valley crosses the Peak Forest Canal by a skew girder bridge. The Peak Forest Canal Aqueduct is a remarkable and lofty construction, stupendous when built, but is dwarfed by the railway viaduct beside it, particularly when the aqueduct is viewed from the train. The aqueduct took 5 years in building from 1795 to 1800 but such was the advance in building techniques and organisation in 50 years, that the viaduct only took 1 year from April 1862 to April 1863 despite being a much larger structure. The viaduct is a simple and yet solid and dignified work, as good now as when built 115 years ago, though carrying trains five or six times heavier than those of the 1860's.

The contractors laid a temporary line from the south end of the viaduct to Wharves beside the Peak Forest Canal; this was to transport materials brought in by canal to the site of work. When the main line was completed, it was decided to make this wharf line permanent and it was made into a branch off the Main Line - the "Marple Wharf Branch". The signal box controlling this junction was therefore called Marple Wharf Junction, - several years before the Macclesfield line joined the New Mills and Hayfield line at this point.

A hand-coloured postcard of Marple Viaduct and Aqueduct.

The Wharf branch consisted of a single track slip off the main line, passing through the cutting bank and crossing the road to the aqueduct, which was the probable course of the tramway built in the construction of the canal locks. Immediately beyond this road, there were two sets of sidings each adjoining a wharf beside a canal pound; the northern single siding was at a higher level than the canal, and would be suitable for transhipping from rail wagon to canal barge, while the southern two sidings were below canal level, so that the wagon floors would be about level with the wharf, and the canal barge opposite; this would be suitable for transhipment both ways. There are no records of what the siding was used to tranship; it may have been limestone or burnt lime, coal or raw cotton destined for Mills at places such as Bollington, then unserved by rail. The wharves may have had a small hand crane to assist in transhipment. The wharves however fell into disuse as less and less traffic passed by canal as the railways network expanded, and it was removed in c.1900. The course of the branch is however quite clear, and the wharves intact if overgrown; the discerning eye can even pick out the remains of rotten sleepers and rusty ironwork amid the bushes.

Beyond Marple Wharf Junction, where a signal box would have been erected in time for the opening of 1865, the line passes through a deep broad cutting, and enters Marple North Tunnel, 99 yards long, which passes beneath the same canal that the viaduct crosses over and the same canal that Marple Wharf is on a level with. This if nothing else brings out forcibly the rate of descent of the Marple locks.

Another cutting through the grounds of Brabyns Hall, and passing under the narrow stone bridge No.28 carrying the coach drive to the Hall brings us to the site of Marple station. The station was and is badly sited; it is crammed onto a natural ledge extended by excavation into the hillside. There was no room to expand and entrance and exit onto a steep hill would be difficult. But in building the line the engineers had great problems to face.

Marple Wharf Junction signal box in the 1960s.

The line is at about 375' above sea level most of the way from Hyde to New Mills. As the line from Romiley approaches the valley of the Goyt the engineers had to either go over or under the Peak Forest Canal to get to Marple - it would be impossible to build a line to the east of the canal as this would require enormous embankments. Going under the Peak Forest Canal at this point would plunge the line into a very long deep tunnel under Marple, and result in heavy gradients to reach New Mills. Going over at a high level, as was in fact done, was the only real choice. Having once gone under the canal it was necessary to get back across its course, to keep to the banks of the Goyt -the alternative would be several miles of tunnel under Marple Ridge. The railway therefore, to cross the canal's path, had to go under it instead of over, which it does passing through Marple North Tunnel. (It must have been quite a feat to blast and pick out a tunnel only a few feet below the canal without causing serious damage to the canal). From Marple North Tunnel the line had to cling to the precipitous sides of the Goyt valley - almost sheer cliffs in places, to reach Strines, hemmed in therefore by canal, and steep valley sides. The railway had little choice of course. The line therefore passed along a steep hillside mid-way between the settlements of Marple Bridge and Marple. That does not explain the present siting of the station, which is highly inconvenient for both places, being approached by very steep hills. It might be argued that a better site would have been just off Arkwright Road near where Stone Row stood, as this was much closer to the then centre of Marple. This is true, and while it would have been possible to get a station in just north of Marple South Tunnel, it would have been very cramped, with no room for platform buildings, very difficult access, and with no room for bay platforms, a goods yard and other extensions which were found necessary. What is more, such a site, while more convenient for Marple would have been very inconvenient for Marple Bridge and Ludworth. It is true that the line could have been carried much closer to the centre of Marple, but only in a tunnel 100 feet or more below the ground - an impossible location for a steam worked passenger and goods station. The site actually chosen, while inconvenient, makes use of a natural ledge to gain some elbow room, and has direct, if hilly, road access; it also is about midway between the settlements of Marple and Marple Bridge.

While the stately viaduct was rising, and the cuttings were being hewn from solid rock south of the station, the station itself was rising, built of brick and local stone; no doubt thousands of bricks arrived by rail and canal to make the buildings.

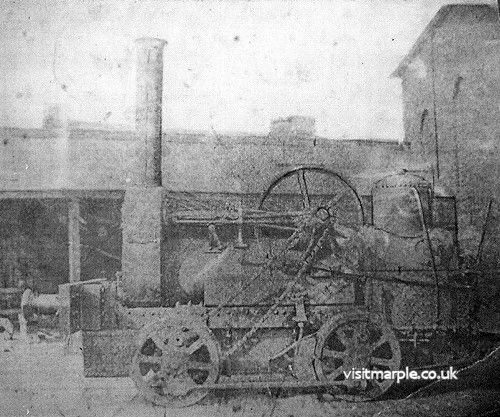

Rattlesnake, the first contractor's locomotive into Marple on 14 June 1863.

The work on the northern section of the line appears to have been rapid for soon after the completion of the viaduct in 1863, work was sufficiently advanced for a locomotive to run across the viaduct and into Marple Station. This locomotive which had the honour of being the first to enter Marple Station was a contractors locomotive called "Rattlesnake". It was an 04-0 tank engine weighing 8 tons with 3' coupled wheels and a boiler pressure of 60 lbs. This little engine had a maximum speed of 10 m.p.h. and had been employed on contractors trains between Hyde and "Compstall". It could pull 8-10 full wagons up the 1 in 70 to Romiley, and on a level road as many as 15 to 20. It was however a very "jumpy" locomotive due to the chain drive, and this probably gave rise to its name. Entering Marple on Sunday June 14th 1863, it made quite an impression on Marple, and a photograph of the locomotive hung in the waiting room of Marple Station until recent years. The locomotive was later used to construct other railways all over the country up to the end of the 19th century.

The site of the station was originally crossed by the "Seven Stiles" footpath, which ran from Bowden Lane to Marple Bridge. The footpath still exists in part today. It was diverted slightly when the canal was built. In 1860 the Hudson family purchased the Brabyns Hall Estate, adjoining the line, and in fact cut by it. The Hudsons being Tractarians, All Saints, the "Low" Church, did not find favour, and they allocated land in a corner of their estate, adjoining the station site, for a Church where they could worship as they wished. Some old residents tell me that it was said in the village that "the Hudsons built St. Martins not for the Love of God or the Church, but to stop the railway getting any more of their land". Presumably they thought a Church as good a barrier to expansion as any.

An illustration of Saint Martin's Church from around 1870, from MLHS Archives.

Anyway as a result of the railway and the building of St. Martins Church, finished in 1870, "Seven Stiles" was diverted; on descending from the canal it was carried over the line by a footbridge, on much the same as its previous line, and then instead of carrying straight on as previously, it was turned at right angles to run between station and Church, to emerge on Brabyns Brow at a little gate behind the Church Lych Gate. Later on the footpath was diverted yet again, when the station was expanded in 1875, and the tall glass and iron canopies erected; it was probably felt not desirable to have a footbridge passing a "stone's throw" away from the glass roof, with St. Martins Church School so close. The footpath was therefore diverted to its present course, high on the cutting top west of the station.

South of the station a deep rock-hewn cutting led to Marple South Tunnel, originally 270 yards long, passing through a rocky outcrop, with a sheer drop to the Goyt Valley, where no railway could pass. The construction of this tunnel and the line to the south necessitated the diversion of the road down to Oldknow's Mill, which accounts for its present dead straight alignment. Beyond the tunnel, the engineers carved a narrow ledge on the almost sheer sides of the Goyt Valley, on one side making a cutting wall 50 feet high, on the other raising a tall embankment on the precipitous slope. Half way along this section passed a footpath ascending out of the valley to Strines Road, which was used every Sunday to conduct the apprentices domiciled at Bottoms Hall to All Saints Church. A footbridge was provided to avoid disturbing so sacred a procession, and it was dubbed "Arkwright's Bridge" after Oldknow's better known partner, and the name is used in preference to the more prosaic official "Bridge No.24" to this day.

Marple Goyt Viaduct from the West in 1906. Compare with the view below.

Emerging from this ledge, the railway was immediately confronted by the Goyt yet again. The course of the line could have followed the eastern bank of the Goyt to New Mills but a much larger viaduct would have been necessary there, so it was decided to cross the Goyt near Strawberry Hill Farm, where a glacial moraine narrows the valley. Here a 5 arch viaduct was built with an iron girder spanning the widest point over the Goyt itself to avoid having a pier on the riverbed. The railway was then taken through the succession of cuttings and embankments as it crossed the alternate ridge and fold of the flanks of Mellor Moor to New Mills; though on occasions where the hillside grew steep the railway was forced once again to cling to a ledge on the hillside. At New Mills the station is in the most cramped spot conceivable; it is on a ledge blasted out of rock, with the resulting man-made cliff towering above, the foaming river Goyt below with a vast, vertical retaining wall to support the railway above it; and immediately to the east are the mouths of the tunnels carrying the line under New Mills itself.

Marple Goyt Viaduct with a Hayfield-Manchester d.m.u. crossing in June 1968 (I. R. Smith)

Strines Station was not so confined, but being on the hillside was not very close to the settlement and Textile Works it was meant to serve which were in the valley bottom.

Such were the engineering works on the Marple and New Mills Section, which while heavy and taxing the ingenuity of the engineer to find a relatively level way through such a difficult and varied landscape, were not exceptional so far as railways in the Pennines and Peak were concerned.

6. Opening of the M.N.M. & H.J. (1865-8)

There were great delays in the construction of the line, due to the varied engineering problems, and it was not until 1st July 1865 that the line onwards from Compstall to Marple and New Mills was opened. Though there are no records of the opening day, great must have been the rejoicing in Marple when the first train entered, no doubt to the accompaniment of brass bands, and rounded off by a sumptuous dinner and toasts of "Success to the Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway". Strines was not however completed until the following year and first appears in Bradshaw's Guide in August 1866. The line was originally single throughout, as was the whole branch from Hyde Junction. Platforms were on one side only - the Down or present Manchester platform at Marple, Strines and New Mills; as yet no goods facilities were provided. The line was worked from the outset by the M.S.L. with a train service of 8 trains a day each way. With the extension of services to New Mills, the temporary terminus of "Compstall" was closed. Four days after the opening, the M.N.M. & H.J. was amalgamated into the M.S.L. At first the M.S.L. showed little enthusiasm for the extension to Hayfield, but was goaded on by reports received that the L.N.W. was surveying for a line from Chapel-en-le-Frith to Sheffield, and was thinking of reviving its moribund Hayfield branch. So late in 1865 the M.S.L. accepted a tender of £27,400 from Rennie and Co. for the construction of the Hayfield branch. Delays however accompanied the construction of this line, not quite 3 miles long. Being in a valley bottom, no very considerable engineering works were required, apart from the 197 yard long tunnel under New Mills (called "Hayfield Tunnel"). The line was opened to passengers on 1st March 1868. The branch was built wide enough for double track, but when opened was single, and remained so for the whole of its existence. except that a short 1/2 mile section out of New Mills was later doubled.

Marple Wharf Junction. LMS Black Five 4-6-0. Unidentified loco on an excursion to Belle Vue.

As yet there were no goods facilities anywhere on the Hyde Junction-Hayfield branch, and these did not come for some years yet, which is unusual as lines generally opened for goods prior to passengers.

Meanwhile the M.S.L. & L.N.W. had composed their quarrel arising out of the entry of the G.N.R. into Manchester in 1857, and had agreed to the construction of a new joint station at London Road, to replace the old station which had only one arrival and one departure platform. The new station was completed in 1866 and used by the Marple and New Mills services. It was partitioned into two separate halves for M.S.L. and L.N.W. with arrival and departure platform for each, and a large iron railing between the two companies, which also had entirely separate offices in the frontage. The M.S.L. side was where platforms 1-4 now are, and in the adjoining roof span the L.N.W. had the space now platforms 5-8. These two 1866 roof spans remain in use to this day, though with later additions.

7. The First Marple Station (1865)

Marple Station, when the line first opened in 1865, was very different from the large affair which existed until demolition in 1970. The line was as yet single, and as the branch carried only a very light passenger service and no goods trains, there would be no loops or sidings.

It is probable therefore in 1865 the station consisted of a single platform, on the Down side, though land was set aside to the east for further expansion when required. The single platform was probably about 200-300 feet long, that is less than half its eventual length, and on this platform were erected the station buildings, adjoining Brabyns Brow Bridge.

All the stations on the Hyde Junction-New Mills branch had only one platform as yet, which was on the Down in all cases except Hyde where the original platform appears to have been on the Up, nearer the town. The original buildings at Hyde Junction, Hyde, Woodley, Romiley, Marple, Strines and New Mills are all on this original single platform, and had a very strong family likeness, though none is quite like any other; little motifs, common however, to them all was the use of a carved stone pinnacle in the shape of a trefoil at the apex of gables, dormer windows, porches etc., a distinctive form of corbel supporting the end of the gable, and similar windows and doors. Original buildings now only survive at Romiley, Woodley and New Mills, of which New Mills is in almost original 1865 condition, and Romiley most altered, but these common features can still be seen. New Mills is unusual in that the initials of the Contractor or Mason - "I.C.B." and the date - 1864, were carved in the trefoiled apex of the dormer window of the station house, where they are visible to the discerning eye to this day.

Marple Railway Station viewed from the Romiley end. On the left in the distance you can just make out the old goods storage shed that was where the car park is today.

The designer of Marple, and almost certainly of all the others, was the Chief Architect of the M.S.L. at London Road, Louis Edgar Roberts M.I.C.E. This gentleman lived in Victoria Park, Longsight and eventually retired to Chorlton where he died in 1916. The style chosen for all the stations was a mild Tudor which was apparent in the stone mullioned windows, "four centred" arches above the 'Perpendicular' style doors, the use of gables and dormers and motifs such as the trefoiled and pinnacled gable ends, barge boards and ornamental corbels. This was then a new style in Marple, but very common in railway lines in the 50's and 60's and often quite pleasing while giving the air of reassuring solidity so dear to Victorian enterprises. The buildings Hyde to Marple inclusive were of red brick with stone ornamentation on door lintels, windows etc. Strines and New Mills were of locally quarried stone, as was Hayfield which was of the same architectural "family". For some inexplicable reason Hyde Junction however was also of stone.

Marple was only then a wayside station, but had buildings larger than any other on the branch except Hyde, presumably as it was considered the most important place on the branch. The site for the buildings was very awkward, as the platform where the waiting rooms were required was well below the level of Brabyns Brow and stairs were necessary to link street and platform level. At road level was an entrance hall and porch which led to a square stair hall with five flights of stairs leading down from street level. At the foot of the stairs were two ticket windows, while the door led onto the platform. This arrangement lasted until the 1920s when a passage was made leading out of the stair hall through the ticket office, and provided with ticket windows. Adjoining the stair hall there was a one storey range of buildings, all entered from the platform. First was a large general office, with ticket windows to the stair hall, then a Ladies Room, with frosted glass, and a lavatory at the rear. The next room was used, in this century at least, as a parcels and left luggage office; next came the gents, and then the general waiting room, which subsequently became a First Class waiting room when a larger waiting room was provided elsewhere, and ended its days as the Station Master's Office; next came the three storey station house, a very commodious dwelling, and finally there was a room for the porters and a store room. Along the front of the buildings was a fine cast iron canopy, filled with glass, supported on corbels on the wall. This was identical to the one still existing at New Mills. The station was probably gas-lit from the start, as gas had by then come to the village.

8. The Effect of the Railway

Before the railway age, the district was dependent on canal and road for transport. The canals were reliable, except in Summer drought and Winter ice, but painfully slow and labour intensive. As we have seen the canal did for a while carry a passenger service, but with a top speed of 10 m.p.h. and a much lower average speed due to the locks, their use was limited for passengers, particularly for long distance travel. There were some turnpike roads in the district but there was no public transport apart from the lumbering common carrier's wagon.

Before the railway age, the district was dependent on canal and road for transport. The canals were reliable, except in Summer drought and Winter ice, but painfully slow and labour intensive. As we have seen the canal did for a while carry a passenger service, but with a top speed of 10 m.p.h. and a much lower average speed due to the locks, their use was limited for passengers, particularly for long distance travel. There were some turnpike roads in the district but there was no public transport apart from the lumbering common carrier's wagon.

The Grave of Edward Ross, Secretary of the MSL 1850-92 in the churchyard of St. Mary's R. C. Church, Marple Bridge. (Author)

One had to be moderately prosperous to own a horse, and only the very rich could afford a carriage. The few stage coaches serving Marple, were a very far cry from the relatively fast mail coaches; even by the best mail coach however it took days rather than hours to reach the capital. Travel by coach or horse was hardly comfortable, and in the winter the roads were often impossible. The coming of railways to Manchester, Stockport, Hyde, Hazel Grove and Disley, placed Marple near railway lines, but left it dependent on canal or road to get to and from the stations. When the railway actually reached Marple in 1865 however, Manchester was brought within 35 minutes of Marple by the best trains - a quite creditable timing, even by today's standards; and other towns in the vicinity were also brought within reach. The coming of the railway brought a far wider range of opportunities before the inhabitants of Marple, especially the lower middle and working classes, who hitherto had rarely travelled. Railway fares, though not cheap, were a fraction of stage coach fares; for those who could afford the fare (which could certainly not include more than a proportion of the working class) it was now possible to travel quite easily and visit Manchester or the Pleasure Gardens at Belle Vue. Gradually people's horizons were widened by the ease of transport offered. In particular the professional and mercantile classes found it was possible to reside pleasantly in country districts such as Marple, and travel daily to Manchester, Hyde etc. The opening of the railway placed Marple among the places considered highly desirable to live, especially in view of the beauty of the surroundings. Accordingly solid mid-Victorian villas begin to appear from 1865 onward on Longhurst Lane, Lower Fold, Church Lane, Hibbert Lane and Station Road -the latter renamed when the railway came, having formerly been Back Lane.

One of the most distinguished early 'commuters' was Edward Ross J.P. who was the Secretary of the M.S.L. from 1850 to 1892. He lived in a very large stone house called 'Beechwood' on Stone Row, built on land owned by the M.S.L. above the Marple South Tunnel. He had a private footpath from Stone Row to the station, descending to the line beside the South Tunnel portal by means of steps, and running along the cutting side of Brabyns Brow, which saved him the detour via St. Martins Road: traces of this path can still be seen. Ross was a devout Roman Catholic, and gave many gifts to beautify St. Mary's R.C. Church in Marple Bridge, where he was buried in 1892; his monument still stands in the churchyard.

Beechwood Manor on 12 September 1978, with the private bridge of Edward Ross J.P., Secretary of the M.S.L. still visible. From Warwick Burton collection in Marple Local History Society Archives.

As the canal age gave Marple the "Navigation Hotel" so the railway age gave the district the "Midland" and "Railway Hotel" (recently renamed the "Royal Scot") in Marple Bridge and the "Railway Hotel" beside Rose Hill station. All three were re-naming of older pubs to keep up with the times - the "Railway Hotel" in Marple Bridge was renamed as early as 1833, inspired no doubt by the success of the L. & M., but the "Hare and Hounds" did not become the "Midland" until the 1870s. The "Railway" at Rose Hill, previously the "Gun Inn", was obviously rebuilt and renamed shortly after the coming of the railway to deal with the new custom.

The trains working the local services to Marple in the 1860s were composed of 1st, 2nd and 3rd class carriages, of wooden construction, and with minimal springs; they were varnished teak and embellished with the company's coat of arms. The 1st Class were upholstered and comfortable up to a point; second class coaches might or might not be upholstered, while 3rd class coaches had 6 a side compartments, with wooden seats. Lighting was by miserable oil lamps let in through a hole in the roof. The locomotives were painted a pleasant Brunswick green, lined out black and white, with reddish brown under-frames. The locos working Marple services would have most likely been rather old 240 or 2-2-2 tanks of diminutive proportions, from Gorton Shed. The trains had no automatic brakes, and there were in fact no brakes on the carriages at all; the driver and guard alone had control over rather primitive handbrakes. Though travel by train was by our standards primitive, with rough riding coaches, uneven track and sharp jolts on starting and stopping, no heat, hardly any light, it was a great deal better and quicker than anything before.