VI. Fin de Siècle. Marple's Heyday 1890-1898

1. The Dore and Chinley Line (1888-94)

You will recall that Chapter IV ended with the opening of the "Midland Junction" Curve, giving the Midland access to the L. & Y. system. The ever ambitious Midland was not however satisfied with its grip on the North-West; a need was felt for a better link between the new empires in Manchester and Liverpool and the older territories centred on Sheffield and the West Riding. When therefore a local Dore and Chinley line was promoted in the 1880's, the scheme was eagerly snapped up by the Midland, and, with its support, authorised in 1888. Work began immediately, but was slow; for out of the 20½ miles of line, over one quarter - 5¾ miles were in tunnel: Totley Tunnel, at 6,226 yards the second longest tunnel in Britain; Cowburn Tunnel (3,727 yards) by contrast is one of the deepest below ground level. Great problems were encountered with underground water in these tunnels; the "Manchester Guardian" remarked at the time that every man seemed to possess the miraculous power of Moses, for whenever he struck rock, water gushed forth! At one point in fact a natural underground reservoir was tapped, and the resulting flow was estimated at 5,000 gallons a minute.

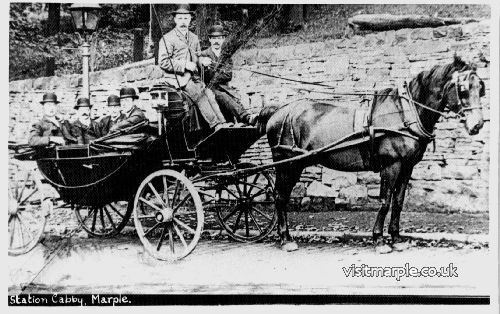

A horse drawn landau outside Marple Station on Brabyns Brow cab rank c. 1900.

The route, usually now known as the Hope Valley Line eventually opened on 13 May 1894. With a route between Manchester and Sheffield only 5 miles longer than the M.S.L., the Midland tried to capture some of the express traffic between the two cities; fast trains were run from Manchester Central calling at Stockport, Marple and one or two other selected Hope Valley stations; the services at Marple were thus further diversified and increased. Local services on the line at first usually ran to and from Buxton, rather than Marple or Manchester.

The express service never really challenged the M.S.L. route, and dwindled away in the early years of the 20th C, but the route prospered for goods traffic, and carried great tonnages between Lancashire and South Yorkshire. It was also found a useful alternative to the heavily graded, and by then very busy route through the Peak, and for some years the occasional St. Pancras or Nottingham and Manchester service ran this way via the South Curve at Dore. Meanwhile goods traffic was causing such congestion on the approach to Manchester that the Main Line was being quadrupled south of New Mills.

2. Marple Train Services: August 1898

Thus with lines radiating to Manchester Victoria, Central and London Road, Liverpool, Stockport, Sheffield and Derby, Marple had by the late 1890's reached the zenith of its main line importance as a Midland main line calling and connectional point.

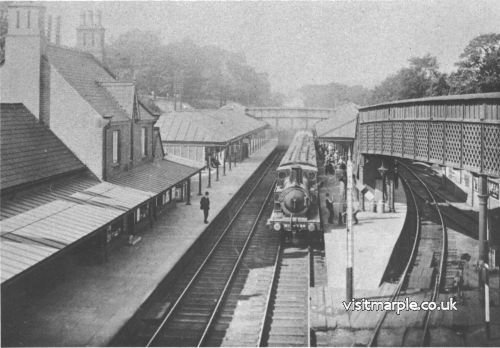

Meanwhile the M.S.L. had opened an independent extension to the Capital in 1899, terminating at Marylebone, changing its name in anticipation to "Great Central Railway" (G.C.) in 1897. Now yet a fourth route was added to the competitive lines between London and Manchester; the Midland was particularly affected, as the G.C. line passed through Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield en route, hitherto mainly served by the Midland. Cut-throat competition ensued, so that by the turn of the century the best St. Pancras-Manchester trains had been accelerated to 4½ hours. This was only achieved on a few trains, omitting most stops, but even so most services continued to stop at Marple, the best of which only took 4 hours 20 minutes between St. Pancras and Manchester. Let us therefore look at the August 1898 train service for Marple, culled from Bradshaw. In all a staggering 109 trains used the station daily, 60 Up and 49 Down; of these only 37 were G.C. trains, the remaining 72 being Midland - over double the number of Midland trains calling in 1887, such had been the growth in traffic. On Saturdays the total was even higher at 122, with 5 additional Midland and 8 G.C. trains, To these must be added almost as many goods trains, mainly Midland, as well as special trains, excursions to Blackpool, South port or the Peak District, and the 8 daily express passenger trains which did not stop at Marple; all told then about 250 trains passed through Marple in 24 hours - an average of l0 an hour, or one every six minutes, day and night! One wonders if the occupants of the station house got any sleep at all with the almost continual rumble of overnight goods trains.

The busiest period was the 2 hours following 8.15 a.m., when no less than 23 trains were booked to call, terminate or start at Marple, in addition to those passing through without stopping. In fact analysis of the timetable shows a continuous stream from the 7.35 a.m. to St. Pancras until the 6.35 p.m. from St. Pancras arrived at 10.40 p.m., with trains on average every ten or 50 minutes, with only four half hour breaks in this cascade of trains. At times this flow reached a torrent with so many trains that one wonders how on earth they a!! got through. For instance, in those two hours from 8.15 a.m., this was what happened. The first of the torrent was a Midland Up local from Stockport, which terminated at the Up platform, and quickly shunted into the Down bay. This was followed at 8.27 by a Down G.C. New Mills-London Road train, the morning business express; at the same moment an Up Midland local for Millers Dale was calling at the opposite platform. 7 minutes later the same Up platform received the 8.35 arrival from Manchester Victoria, which terminated and shunted into the Up loop, before the train with which it connected, the Midland West of England Express from Central, drew in at 8.48, and soon departed again for Bristol. Meanwhile at the other platform, a Down G.C. Hayfield-London Road local departed at 8.47, followed 3 minutes later from the Down bay by a local for Stockport and Altrincham, formed by the loco and coaches of the 8.15 arrival from Stockport. 7 minutes later another Up local from Stockport arrived and shunted out of the way. After a break of 10 minutes, an Up Midland semi4ast for Matlock Bath drew in at 9.7; behind it at 9.15 arrived another Up train, a Midland non-stop service from Victoria, to connect with the following St. Pancras express. The Victoria train had however to quickly shunt out of the way into the Up loop, as 4 minutes later at 9.19 an Up G.C. local for New Mills was due, while at the same time in the Down platform a Midland semi-fast from Rotherham and Sheffield halted for 3 minutes; it left for Manchester Central at 9.20, closely followed 3 minutes later by the return to Manchester Victoria of the train which had arrived at 8.35- this would leave from the Down bay, if there had been time to get the stock across between trains, or if not, from the Up loop. Traffic was now reaching a crescendo, and at 9.25 an express from Liverpool Central arrived, terminated in the Up platform, and was quickly propelled into the Up loop, and the engine turned on the turntable.

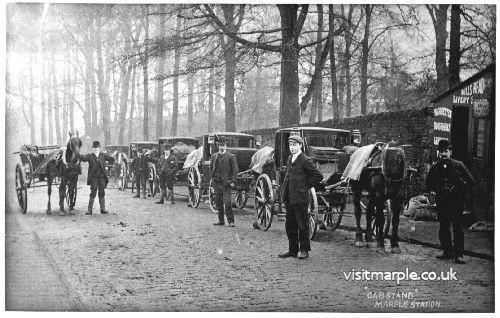

The Cabstand on Brabyns Brow outside Marple Station in the pre-motor age. c. 1900

Within a few minutes the Manchester-St. Pancras Dining Car express drew in at 9.31, with through coaches for Nottingham and Sheffield also attached: promptly the shunter detached the rear 3 or 4 coaches destined for Sheffield, and the main express departed at 9.36; the Sheffield coaches were quickly provided with an engine (probably off the 8.57 local arrival from Stockport) and left 4 minutes later. At the same moment as this caravan like train was being dealt with at the Up main platform, a Derby-Manchester express was being divided at the Down main platform. Arriving at 9.30, the rear 2 or 3 coaches were shed for Manchester Victoria, and left in the Down platform; once the main train had left for Central at 9.35, the loco and coaches which had been waiting in the Down bay since arrival from Victoria at 9.15, drew out, backed onto the Derby coaches and left for Victoria at 9.38. Hard on its heels, the connecting 9.44 for Liverpool left from the Up loop, with the train that had arrived at 9.25. It can thus be seen that at approximately 9.35, all four platforms were occupied with 7 trains or portions standing in them simultaneously destined for Liverpool, Manchester Victoria, Manchester Central, Sheffield, St. Pancras and Nottingham, and one from Stockport; two trains were dividing simultaneously, there were 4 departures within 5 minutes and three light engines shunting from line to line. No sooner had all these trains left however than an Up Midland Derby Slow called at 9.45, at 9.52 an Up G.C. Hayfield; at 10.01 a Midland Down Millers Dale - Central Slow halted for 4 minutes for water, followed at 10.08 by a G.C. Hayfield-London Road. There then mercifully followed a rare 30 minutes break until the next train was due, a gap which was no doubt filled with a steady stream of goods and special trains; this pattern of intensive usage was repeated several times during the day, though not quite to such a fever pitch.

As has been said, the Midland stopped 42 Up and 29 Down trains at Marple, of which about % were express as opposed to local services. 6 trains from and 7 to St. Pancras called, and of these 5 each way stopped to detach or attach through coaches to or from Manchester Victoria, Bolton and Blackburn. These portions to and from the L. & Y. system were very popular in their day, as Midland coaches were so comfortable by comparison with those of other companies. The coaches used on these trains were 12 wheeled bogie 1st and 3rd composite non-corridor stock, hauled throughout by Midland locos. They usually called at Darwen, Bolton, Salford and Manchester Victoria, though one or two called at Bromley Cross and Turton stations - what on earth such trains were calling at such remote places high on the Lancashire moorland can only be surmised - perhaps some important personage lived nearby. Trains conveying 1st class sleeping cars between Manchester and St. Pancras also stopped at Marple; Liverpool portions were usually attached or detached at Stockport, though a few expresses had Liverpool connections at Marple; but the Up overnight train was marshalled up at Marple with portions from Liverpool, Blackburn and Manchester Central, which must have been quite a task.

Some of these St. Pancras trains were very fast indeed: the 12 noon from Central ran nonstop to Marple, where it picked up a Blackburn portion; from Marple it ran non-stop to Leicester (avoiding Derby via the Chaddesden Loop) in 98 minutes for the 87 miles, an average of nearly 54 m.p.h. - not bad for 1898! The train reached St. Pancras without any other stop at 4.20 p.m., 3 hours 55 minutes from Marple. It is difficult now to imagine a St. Pancras express calling at Marple and Leicester only after leaving Central! There was another non-stop Marple to Leicester run on the 4.10 p.m. from Manchester, and another on the 12noon St. Pancras-Central; such was the competition for London-Manchester traffic that on occasions even Derby was avoided.

The latter days of steam at Marple. B.R. Standard Class 5 4.6.0 heads a train of empty stock for a return Belle Vue - West Riding excursion on Easter Monday 1967. These locomotives were common on the line in the mid 1950's when they used to appear on local "running in" turns when brand new from Derby. Note the site of the Up loop platform 4 (left) and Down bay platform 1 (right) at the north end of the station. (I.R. Smith). (From Marple Rail Trails)

Cross Country services to Bristol and between Liverpool, Manchester and Nottingham called, and there was also the Midland's Sheffield-Manchester service, some of which ran to and from Rotherham Westgate. While some of these trains were entitled "Sheffield Expresses", others called at nearly all the stations on the Hope Valley line, and even the best usually stopped at Heeley, Dore and Hope or Edale, or some other station, even if only to take up or set down. There were in addition some even more exotic through coach workings, such as one from Southport Chapel Street to St. Pancras, via the C.L.C., Manchester Central and Marple. In the summer there were several Blackpool services calling at Marple. For instance the 4.50 p.m. Blackpool (Talbot Road)-Sheffield train was first stop Marple, though the through train to Leicester and Nottingham on the Up stopped at Salford and Manchester Victoria, and the equivalent Down train at Miles Platting (change for Victoria) and Poulton.

The basis of the local services was the slow stopping trains between Manchester and Derby, which took over 3 hours for the 60 miles, and other locals which had their terminus at Millers Dale, Matlock or even Ambergate; there were also semi-fast trains which called at principal stations such as Chapel-en-le-Frith and Rowsley to Matlock, Derby or Nottingham.

The number of services Marple enjoyed to various principal points in August 1898 are best summarised in table form:-

| To Marple | From Marple | |

| St. Pancras | 6 | 7 |

| Leicester | 8 | 7 |

| Nottingham | - | 6 |

| Derby | 12 | 15 |

| Birmingham | - | 3 |

| Bristol | - | 3 |

| Sheffield | 5 | 6 |

| Rotherham | 1 | 3 |

| Liverpool | 7 | 8 |

| Blackpool | 2 | 1 |

| Southport | 1 | - |

| Blackburn | 5 | 5 |

| Manchester Victoria | 12 | 8 |

| Manchester Central | 17 | 20 |

| Manchester London Road | 20 | 17 |

| Stockport T.D. | 16 | 22 |

The coaching stock employed on Midland trains had an enviable reputation for comfort, especially for 3rd class passengers, and for internal and external cleanliness. All were painted in a rich shade of red known as "crimson lake", lined out black and gold, and embellished with the Company's coat of arms. By now the Pullman cars, which had been running since the 1870's were becoming rather antiquated, and were replaced on night trains by specially built 1st class sleepers. There was also a growing demand for dining cars, and refreshment stops were going out of favour as causing delay. In 1897 the Midland introduced magnificent 1st and 3rd class dining cars on the Manchester run. These were 6Oft. long, with 6 wheeled bogies and had handsome clerestory roofs. At the same time new coaches were being provided with lavatories reached by short internal corridors - as yet the public were not ready for full corridor trains as they were regarded as invasions of privacy. Another feature of Midland coaches was steam heating, as on most British trains people had to rely on foot warmers for warmth; these were giant "hot water bottles" of brass, filled with hot water or heat giving chemicals. A Marple gentleman still living until a year or two ago remembered using these on trains from the station, his father tipping the fireman for a fill of hot water, and he and his brothers and sisters squabbling about who should have their foot on it. Not for nothing did railway guides enjoin wrapping up well against the cold when making a train journey. Trains were also still gas lit, as electric lighting was still in its infancy. The engines hauling these magnificent coaches would seem very small to our eyes, but were supremely elegant, and beautifully finished since c.1883 in the same crimson lake as the carriages, with black and gold lining out, and the Company's armorial embellishment; they were always in immaculate condition, even underneath. They could also run remarkably fast on occasions, despite their small size. The most famous class of engine in use on Midland expresses at this time were the Johnson "Spinners", so called because of their 7'9" single driving wheels, which had a tendency to slip and spin when starting, but were exceptionally fast and free runners. Other 4-2-2's and also 4-4-0's, with almost equally large driving wheels were also common on the express services calling at Marple. Less up to date engines would have been seen on local and stopping services, though the Dore and Chinley had 15 4-4-0's built specially for it in 1893. Goods trains were still worked by he ubiquitous 0-6-0's, some of great antiquity; as Midland engines were so well maintained, they tended to last a long time! Coaches on local and semi-fast trains were composed of 6 wheeled coaches, and some 8 wheelers. The G.C. share of activity at Marple was far less intense than that of the Midland, and hardly changed from 1887; 17 Up and 20 Down trains were run of which a few started or terminated at Marple. One G.C. train was even marshalled up at Marple: separate trains left London Road at 5.10 p.m. calling at all stations via Guide Bridge and at 5.37 p.m. calling at Ashburys to take up, and Romiley, reaching Marple in 23 minutes, where the two trains combined to go forward to Hayfield. Of the G.C. trains 11 each way ran to and from Hayfield, and 2 used New Mills as a terminal. Trains were almost equally divided between the Bredbury and Guide Bridge routes, if anything favouring the latter. The G.C. trains ran at irregular intervals, with gaps in departures of well over an hour throughout most of the day. On Saturdays 2 extra trains were run to and from Hayfield, and another as far as New Mills only, for the benefit of trippers from Manchester, Ashton, Hyde etc. enjoying a half day trip into the countryside. Some of them started from Guide Bridge or even Gorton, and were 3rd class only.

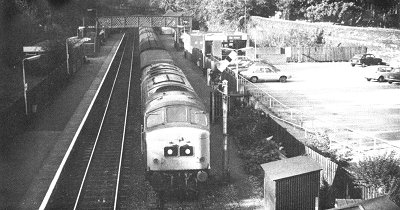

The "Harwich Boat Train" (1516 Manchester Piccadilly to Harwich Parkeston Quay) heads south through Marple on the 7th October, 1978. The station is largely as it is now except for the introduction of colour light sinalling and demolition of the signalbox. (Author).

G.C. services were generally worked by green-livened tank engines from Gorton Shed (whereas Midland engines came from depots as far afield as Liverpool, Leicester and Sheffield, or nearer home Trafford Park, Belle Vue, or Rowsley), such as the class 3 2-4-2 tanks. The coaching stock livery was changed in 1896 from varnished teak to a very smart style of buff lower panels and french grey upper, lined out gold. But the new livery did not wear well or stay clean in the industrial north, and in 1908 coaches reverted to varnished teak.

In all 45 trains each day left Marple for Manchester, and 49 arrived from that city, linking Marple to the 3 most important Manchester termini by a variety of 4 routes. All told the 109 daily trains terminated at 22 different places, linking Marple directly to well over a 100 different stations in 13 counties. Incidentally, in 1904 as a result of the change of name of the M.S.L. to G.C. and the joint acquisition of a colliery branch from Shireoaks to Haughton in South Yorkshire, the Sheffield and Midland Committee was renamed the G.C. and Midland Joint Committee, which thus controlled two distinct and remote lines. Similarly in 1907 the old Macclesfield Committee became the G.C. & N.S. Joint Committee.

3. Improvements to Marple Station

The station as completed in 1875 and described in Chapter IV Part 3, remained much as built until demolition in 1970; the Midland must have often wished for additional platforms and facilities, with the vast and growing number of trains calling and passing through. But there was no room to expand without formidable engineering works on one side, or sweeping away St. Martins church on the other. Various small scale improvements were however made. On the Down side the original 1865 waiting room was proving inadequate, and a large bay fronted wooden waiting room was provided between the station house and bay platform; not known when, was probably about 1885. The old room became a 1st class waiting room. Behind the new waiting room was erected another wooden building to house the platform foreman; this building had originally been the checkers office in the goods yard, but was moved and re-erected. An improvement to the goods yard in the last years of the 19th C. was the addition of an additional siding between "shed road" and "back road" to deal with additional coal traffic, which became known as "middle road"; between it and "back road" a cobbled cart road was laid and beside its buffer stop a weigh bridge was installed. This was later moved to beside the gateway onto Brabyns Brow.

Marple in its heyday c. 1910. View northwards from Brabyns Brow Bridge. At the Up platform the MSL 2-4-2 tank No.735 takes water on an up Hayfield train, while large numbers of passengers get out. A down goods train can just be seen on the opposite line. Notice the up loop, "table road" and goods shed to the right.

As we have seen a number of trains terminated, divided or were marshalled up at Marple - in fact the August 1898 timetable would have required about 25 engines to use the turntable in one day. The turntable installed in 1875 was 45 feet long, and was becoming rather short for the increasing size of engines of the late 19th C. We find a reference in the minutes of the Midland Board's Loco Committee in 1896 as follows: "it was suggested that the 45' turntable at Marple be replaced by one of 50'. This was sanctioned by the General Purposes Committee", and in 1897 "it was reported that the S. & M. Joint Committee agreed to a 50 foot engine turntable being put in at Marple, the Midland Co. to bear the whole cost of the work, and to pay £10 rent for the site of the turntable" (i.e. to the M.S.L., per annum). The turntable was installed, probably in 1898, in a hollow carved out of the embankment, just S.E, of Brabyns Brow; this great excavation is still visible today, though the actual table pit is filled in. The reason that a completely new turntable was required was because there just was not room for a larger table under the footbridge between main line, "shed road" and retaining wall. For a time the old turntable remained in use alongside the new one (it is still shown on the 1909 OS. 25" map), but was eventually removed and a siding laid over its site; this was still however known as "table road"! There are no records of when the second 50' turntable was removed, but it would have declined in usage with the great alterations to Midland services in the early 20th C. It was probably removed sometime after the 1st World War, and it is known that the table was taken away for re-use at Buxton Midland Loco Shed.

The Midland Railway was responsible for the maintenance of half of the Works and Ways on the S. & M. Joint Line, which came under Derby North Maintenance District. The Midland share extended from Hayfield, through Marple, to Woodley Junction on the Hyde line, to Bredbury Junction on the C. L.C. and Reddish Junction on the Bredbury Route. The Midland were responsible for all track, signalling, signal boxes, bridges, viaducts, gradient posts, mile posts, telegraph wires, stations and lighting. Station maintenance and painting was let out on contract, but the rest was performed by the Midland; the track was maintained by gangs of platelayers stationed all along the route, each of whom had his "length" to patrol each day; for bigger jobs they would form a larger gang to tackle it. All other general maintenance work was done by staff based at Romiley, and included carpenters, painters and a blacksmith. The Midland erected its mile posts along its portion of the S. & M.; accordingly a Midland style mile post reading 176% (from St. Pancras via Derby) can still be seen at Marple Station affixed to the retaining wall of St. Martins Churchyard, near the signal box.

The 12.20 d.m.u. from Manchester Piccadilly to New Mills calls on 12th September 1978. Note that it is carrying an incorrect destination blind for "Barrow"! Compare this view with the one adjacent taken from the same place in c. 1910. Since this photo was taken, the Signal box has closed, and colour lights replaced the semaphore signals. (Author)

4. Operating at Marple

To deal with these 109 trains a day, a very large staff was required. Presiding over the hierarchy was the Station Master; after Mr. Rowbottom, whom we have already met in the 1870's, came Mr. Hawkins who left in the 1890's, and was the last to live in the Station House for many years. He was followed by Mr. Keighley, who was only a small man, but he ruled with a rod of iron, and his staff were always careful to call him "Sir"; he supplemented his railway income by giving shorthand lessons at a 1d each.

Below the "boss", in the Booking Office was the "Chief Clerk", and several "Second Clerks" on various turns, plus a Junior Clerk to assist in the busiest part of the day. These Clerks would book tickets, give information, and deal with all the station accounts, and also the documentation for parcels by passenger train; the Junior Clerk was no doubt often sent to the Parcels Office to do this. Also under the boss, were two Platform Foremen on each shift, one for the Up and one for the Down. Under them they had two Porters each, and an additional Porter to assist as required; the Porters also had to help load and unload goods traffic. There were normally also two Ticket Collectors on duty, one from each company, Midland and G.C.; each collected tickets from their own company's trains, to be bagged up and sent to Derby or Manchester - no doubt however they helped each other out on occasions! They had a little office beneath the footbridge on the Down platform. There was also one shunter on duty on each shift to couple and uncouple coaches and locomotives on all trains dividing, joining and terminating.

On the goods side there was a Chief Goods Clerk, and a Junior Clerk, who did all the goods documentation in the little office attached to the goods shed. There was also a Checker, who checked all the wagons sent out of the yard were correctly labelled, took details off wagons coming into the yard, kept a watch on road vehicles entering the yard, and operated the weighing machine. There were also day and night goods porters who loaded and unloaded all goods traffic from wagons.

Originally, when there were three signal boxes, north and south required two full time signalmen, plus a porter-signalman for 4 hours of the night (men worked 10 hour shifts then), and the centre "knob-up" signal box had a porter-signalman on early and late turns. However when one box replaced three, only two full time signalmen and one porter-signalman were required. Finally a Lampman was employed to keep all the signal lamps filled with oil, and generally clean and in order. He was housed originally under the signal box, but later a corrugated iron hut was provided between the two short sidings at the north end of the station. In all therefore the Station Master presided over about 40 staff, of whom 15 or so would be on duty at any one time; labour was cheap and plentiful in those days.

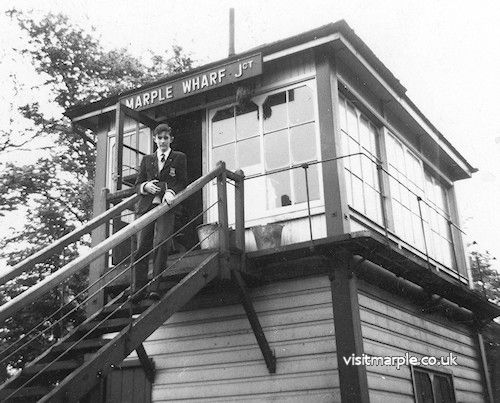

Marple Wharf signal box. Chris J. Beckett on the steps.

But the station with such a heavy train service required a large staff; passengers changing trains often carried heavy luggage, especially businessmen with their heavy "skips" of samples, which the platform porters had to deal with. In many cases the gentleman would require a cab to take him to his destination - there were always a couple of horse drawn cabs or carriages awaiting on Brabyns Brow, and sometimes the queue extended back to St. Martins Lych Gate; the unfortunate porter would have to heave the luggage up the stairs to the cab. Porters also had to attend to trains, load and unload parcels and passengers luggage, help passengers out, close doors, collect tickets if there were more passengers than the ticket collectors could deal with, and keep the station clean and tidy between trains. The porters also had to handle mail bags, which G.P.O. staff used to drop down the stairwell from Brabyns Brow - one hopes railway staff were more careful with their parcels! The goods yard was also a hive of activity. There were four basic types of traffic dealt with at Marple: coal, livestock, general merchandise in full wagon loads, and general merchandise in less than wagon loads ("sundries"). General merchandise could be delivered or collected by the Railway, usually through a local carrier except at the larger goods depots, or carted by the customer. Coal was entirely in the hands of the various merchants who came to collect their coal from wagons in the yard. It was difficult to deal with livestock at Marple, as the lack of space precluded permanent pens; on Monday, which was cattle market day, temporary pens were erected by inserting wooden posts in permanent sockets in the yard, and roping up between them. To get cattle, and other livestock, out of vans or wagons, which were usually placed in "shed road" on the south side of the shed, a portable wheeled ramp was used. This traffic grew to such an extent that early in the 2Oth C. the cattle market was erected opposite, and at one time the provision of a permanent siding beside the second turntable was considered to avoid driving the cattle across the road. Sheep, cattle and pigs also arrived by train on Tuesday night for slaughter in the various Marple butcher's premises. There was also quite a lot of milk traffic, with churns being dispatched daily by passenger train each morning for dairies in Manchester and Didsbury.

General merchandise was dealt with out of doors if it was not likely to take harm e.g. agricultural machinery, lime, or minerals, but the rest which needed to be protected from the weather passed through the goods shed. The purpose of the shed was to allow goods to be loaded and unloaded under cover, and to warehouse traffic for collection or delivery; to facilitate this the interior was provided with a raised platform, occupying the entire floor space, except for the railway line on one side and two loading bays on the other, which permitted a road vehicle to back into the shed and load under cover. Both bays were provided with cranes of 1½ tons capacity. Through this shed would pass such merchandise as sacks of corn to be ground into flour at Flowerdew's Corn Mill at Marple Bridge, chemicals for the Mellor Bleach Works at Hollywood, farming produce, raw cotton for the mills of the district and returning consignments of finished cotton or calico from Compstall; the entire requirements and produce of the district passed through this shed or the yard, unless it went by railway owned canal. G.C. Goods Services were provided by a daily pickup from Guide Bridge and Woodley to Marple and Hayfield, and by Midland Goods trains to and from Ancoats, Sheffield, Rowsley and Buxton. One train nicknamed the "Bull", perhaps because it carried livestock, was due from Ancoats every morning at 1 a.m., but was frequently late, with a result that the unfortunate goods porter who had to deal with it often had to wait about for it all night until it came. There was also a night fish train from Fleetwood to Derby, which called to set down some of the catch for Marple fishmongers.

The Railway Companies usually employed local agents to perform cartage except at the larger depots: in Marple at the turn of the Century this was a Mr. Yarwood, more commonly known as "Old Yarwood". The Midland also had a local parcels receiving agent in Marple, a Mr. W. Bradley of Church Lane.

In the early 1900's as a result of the burning down of Oldknow's Mill, the great mill ponds were turned into boating lakes; the boats for these arrived by train, and were carted down to "the lakes" on Bowden's horse drawn coal lorry. These "Roman Lakes", as they were called, proved a great attraction for trippers from all the Manchester district. Marple, and also Strines, New Mills and Hayfield, were already very popular destinations for excursionists, and Saturday half day trippers, as we have already seen from the extra trains run on Saturday afternoons to cater for them: for instance a handbill for the Easter Bank Holidays of 1898 advertises morning and afternoon excursions from Oldham and Ashton to Marple and Hayfield at 1/- (5p) return. A particular attraction advertised at Marple, before the Roman Lakes were established, was the Compstall "Spring Gardens", a set of pleasure gardens on Compstall Road, recalled by the present pub of the name. But the Roman Lakes brought a vast influx of visitors, for whom Marple was the nearest place offering beautiful countryside and amusements within reach of the city. On occasions the queues of excursionists waiting to return home of an evening stretched several hundred yards up Brabyns Brow as far as the canal bridge.

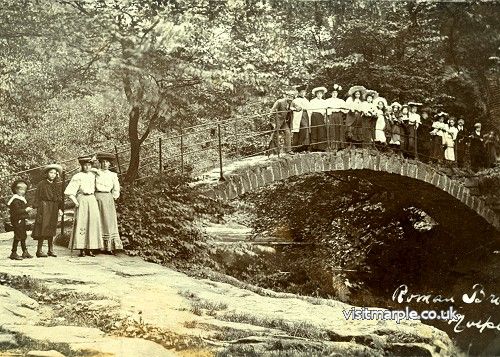

Visitors to Roman Lakes pose at Roman Bridge. From Marple Local History Society Archives.

According to a G.C. handbook of 1900, a third class season ticket between Marple and Manchester London Road via Hyde or Reddish cost £7 per annum! For an extra 10/- (50p) p.a. it could be made available to Manchester Central or Victoria, and for £8 all told it was available to all three termini by the four routes. Rose Hill was a little dearer at £7 12s.0d. (£7.60p) p.a., via Hyde or Reddish, but they were also available to Marple.

For Middlewood very complicated arrangements were in force; for £12 2s.0d. £12.l0p) p.a. your season could be made available from Middlewood or Disley to London Road via Hyde, Reddish or Longsight which gave 6 possible permutations of route in all. A Marple-St. Pancras return ticket cost £1 9s. 3d. (£1 .46p) third class, £2 7s. 2d. (£2.36p) first -though it must be remembered that the 3rd class fare was about equal to a skilled artisan's weekly wage, the equivalent of perhaps £70 in today's value. If you took your dog with you it cost an extra 4A (20p). Through bookings were available from Marple to almost any station in Great Britain and Ireland; the Midland was particularly generous in the issue of "Tourist" tickets at reduced rates. For instance a return "Tourist" to Lowestoft cost 29A (£1 .45p) or to Southport 6/6d (321/2p). If you fancied a trip to Bideford for Westward Ho! in Devon, this would cost you 37A (£1 .85p), while if you choose to go a little further afield, the Great Central would be delighted to oblige with a through booking to Hamburg via Grimsby at £1 1 is. 6d. (£1 .571Ap) 3rd class "Steerage" or £2 18s. l0d. (£2.94p) 1st class "Saloon".

Some of the regulations of the Midland Railway make interesting reading, and give some indication of the type of passenger and traffic to be expected at a busy station. Commercial Travellers, for instance, were not allowed to take with them free in their luggage such things as "children's mail carts, patent corking machines, small gas engines, patent scrubbing machines, polyphons, chair legs, orchestraphone cases, and automatic penny-in-the-slot pianos", but had to pay full parcels rates on these. Special reduced rates were however available for the excess luggage of "Strolling Players, Burlesque and Musical Companies, Equestrian Parties, Emigrants", and for the "demonstration plant of Lecturers employed by the Church of England Incorporated Society for providing homes for Waifs and Strays, and that of Lady Lecturers employed by cooking stove manufacturers, lecturing apparatus of the National Refuge for Destitute Children (when accompanied by the Secretary) and "Dissolving View" and other apparatus accompanying Band of Hope Lecturers". Quite a mixed company! You name it, the railway had rates for it, from black puddings and samples of temperance beer (whatever that was) to mistletoe and patent clips for horseshoes. The Railway Companies were obliged by law to carry everything (the so called "common carrier obligation"); hence we find that "small wild animals such as pumas, jackals, tiger cats . . . are charged at 6d. (2½p) per truck per mile "while" elephants carried in covered carriage trucks are charged at 1/- (5p) per mile per truck - whether the truck is specially strengthened or not". Potential consignors of wild animals in the early 20th C. would have been relieved to know however that "camels and zebras are charged at the horse rate, according to the number of stalls occupied", and could even be conveyed by passenger train in horse boxes.

In 1900 the railways had an almost complete monopoly over all inland movements over a few miles for both goods and passengers, and accordingly even a smallish goods yard like Marple was very busy. It is however too easy to look back to this as a "golden age"; it must be remembered that the steam engine was dirty, that manual work in the age of coal and iron was hard without modern aids, that clerical work involved much drudging over ledgers of hand written figures by gaslight, and that men at Marple Station worked 10 or 12 hours a day for little over a £1 a week. But it is fair to say that the railways were at the height of their power, pride and prosperity, and on a well run line like the Midland things were spick and span and beautifully maintained, and that men had a real pride in their work and loyalty to their Company.

A Basic Railway Halt at Strines on September 12th 1978. A solitary passenger alights from the 11.11 New Mills Central to Manchester stopping d.m.u., looking north (Author)

5. Strines

Strines Station first appears in Bradshaw in August 1866, and originally had one platform, the Down, on the single line to New Mills. The original buildings on the Down were of stone and consisted of a low, one storey waiting room, with a veranda type shelter in front; adjoining the waiting room, and under the same roof was a tiny booking office about 6' wide. Behind this was the Station Master's house, with living room and kitchen on the ground floor, and 3 tiny bedrooms above. Next to this were the Gents. A Ladies Room was later added behind the main waiting room. The buildings on the Up consisted merely of a wooden open fronted shelter, probably dating from when the line was doubled. A footbridge linked the platforms, and the station was gat lit, at least by 1900.

Strines - a typical Midland Railway style small country station, with fine gas lamps, neat stone buildings and a large wooden goods shed, c 1962. (Mowat Collection). (From Marple Rail Trails)

Adjoining was a small goods yard, with one siding to the West for coal, and another to the east, 9oing into quite a sizeable goods shed, where traffic to and from the large Strines Calico Print Works provided the bulk of the business, with a little agricultural merchandise. There was a small outdoor crane of 2 ton capacity, and another in the shed.

Strines, like Middlewood, had, and has, no houses in the immediate vicinity. Passenger traffic was never heavy, but in the days before the bus and car, it was the only public transport in the area; and with the passage of years, houses were built in Strines village, and some residential traffic built up. Few houses were however built near the station due to unsuitability of land in the wet valley bottom or on the steep hillside. The goods yard was however busy enough. Staff would probably consist of Station Master, Signalman, a Clerk (one on each shift) for goods and passenger work, and a couple of Porters, again for goods and passengers; in all perhaps 10 staff were employed at the station, and in the busiest part of the day 5 might be present at once.

Strines in its heyday c. 1910, looking south. Note the large wooden goods shed (right)

The mainstay of Strines' service were the M.S.L. and later G.C. Hayfield-London Road trains, though the Midland stopped some of its local trains between Manchester Central and Derby or Sheffield as well. In 1875,7 M.S.L. trains called in each direction, and 2 Down and 3 Up Midland "Derby Slow" trains, a total of 19 trains in all. By 1898 still only 5 Midland trains called en route to or from Millers Dale or Derby, but the G.C. total had nearly doubled, with 13 each way, and 18 on Saturdays, for the benefit of half day trippers, some of whom came to Strines. By 1910 the number of G.C. trains had increased to 18 Up and 17 Down. Midland services were down to 2 each way, though they were a fair assortment - on the Up, one to Chinley and another to Matlock, and on the Down one from Millers Dale, and one from Buxton! Strines was in the early 2Oth C. a good example of a small but thriving country station, as Marple was of an important medium-sized station.

A Liverpool - Sheffield d.m.u. passes through Strines on 3rd April 1966 (J.R. Hillier).