IV. Marple's Expansion. 1872-1889

1. The Origin of the "Cheshire Lines Committee" (1859-74)

To trace the steps by which Marple now on the Midland through route to Manchester became an important centre on that route we must retrace our steps to 1859. In that year two schemes were floated - the Stockport and Woodley Junction Railway, to run from the M.S.L. at Woodley to a low level station in Stockport, and the Cheshire Midland Railway, an extension of the M.S.J.A. from Altrincham to Northwich. Both were initially locally promoted, but Sir Edward Watkin, the forceful General Manager of the M.S.L., encouraged both these schemes seeing in them a means of occupying territory west of the M.S.L. main line. These lines were authorised in 1860, and in the same year Watkin engineered the "local" promotion of the Stockport, Timperley and Altrincham Junction Railway to link the two lines, and the West Cheshire Railway to extend the Cheshire Midland towards Chester and the Wirral. These two lines were authorised in 1861.

Later on the G.N. (which as you will recall had started running into Manchester in 1857) was also looking for further western outlets for its traffic and was induced to join the M.S.L. in financing and when completed working the four lines mentioned. A joint Board of Directors known as the Cheshire Lines Committee was set up in 1863 to do just this: at the time the name was appropriate as all the lines were in Cheshire, but became anomalous when the major sphere of activity became Lancashire!

The first line to be completed was the Stockport and Woodley which opened in 1863 to a temporary terminus in Stockport at Portwood; the Stockport-Altrincham line linked up with it in 1865 with a station nearer the centre of Stockport at Tiviot Dale. Portwood closed in 1875 but remained open for goods, a purpose it still fulfils today as a private siding. The lines on into Cheshire, and a Woodley-Godley Junction cut off, completed the original C. L.C. "Main Line" from Godley Junction to Chester.

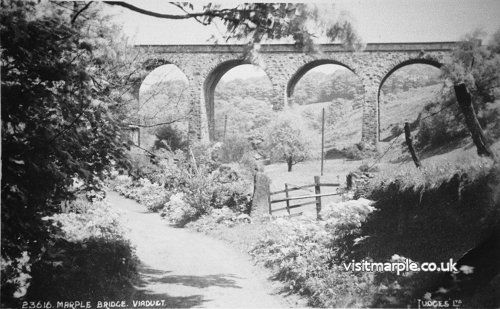

The Railway Viaduct at Roman Lakes viewed from the direction of Roman Bridge.

The M.S.L. had for many years been casting envious glances at the glittering prize of Liverpool. It had depended for access up till now on running powers over a variety of local railways, and over the L.N.W. into Liverpool proper. The M.S.L. and G.N. had however got hold of a local line, the Garston and Liverpool opened in 1864, and made it part of the C.L.C. However the local line on which the M.S.L. depended for access to Liverpool had fallen into the L.N.W. net; Watkin therefore decided that an independent route to Liverpool was essential to their interests and would almost certainly attract the interest and financial support of the G.N. and Midland.

The 1865 session of Parliament authorised the construction of such lines to run from Skelton Junction on the Stockport-Altrincham line, and from Manchester (Cornbrook) to Glazebrook and thence via Warrington to Garston. The final portion of the route into Liverpool Central station was already authorised. These lines received very widespread support in both cities, whose traders were very dissatisfied with the facilities provided by the L.N.W. and L. & Y.

The L.N.W. was furious and initiated instant reprisals and the M.S.L. was threatened with withdrawal of running rights between Ardwick and London Road. Watkin counter-attacked by proposing a railway across Manchester from Ancoats to the M.S.J.A. and C.L.C. lines at Cornbrook, with a large Central Station on Portland Street, and a wayside station at Piccadilly. Unfortunately this scheme met with opposition due to the interference it would cause to Manchester's streets. The L.N.W. then retaliated in another direction by promoting a "Sheffield Buxton and Liverpool Railway" to run from Sheffield to Chapel-en-le-Frith via Castleton. Sir Edward Watkin remarked that it was a "veritable High Peak line, evidently conceived in pique". The warring Companies however were eventually forced to compose their differences.

The Midland was by now almost ready to enter Manchester but had no intention of resting on its laurels once it had got there; it would be content with nothing less than the subjugation of the whole North West! The Midland was therefore very interested in the C.L.C. and was admitted as third partner in 1866.

As Watkin had expected, the Midland and G.N. were prepared to put up capital for the Liverpool extensions, and construction pressed ahead. The lines were completely opened by 1874 though at Manchester the terminus was only a temporary one at Cornbrook. The new lines were a great success, not least between Liverpool and Manchester, where for so long the L.N.W. had used its monopoly as an excuse for high fares and slow services. The C.L.C. changed all this, and in 1877 reduced fares and started its famous hourly expresses, taking only 45 minutes.

What is more the Midland from 1874 had access to Liverpool and immediately commenced a combined London St. Pancras-Liverpool and Manchester service. However the Liverpool portions had to be worked to Manchester London Road and back the way they had come to Woodley to gain access to the C.L.C., because Woodley was not a suitable place to divide or join trains. This was obviously a very time wasting procedure.

2. The "Manchester and Stockport" Railway (1866-75)

When the Midland was still completing its line from Millers Dale to New Mills, the M.S.L. supported a nominally local scheme, the "Manchester and Stockport Railway". As originally promoted it was to have a main line from Ashburys to Brinnington Junction on the C.L.C. Main Line just east of Portwood; but the M.S.L. added a "branch" from Reddish Junction to Romiley which would provide the Midland with better access to Manchester London Road than via Guide Bridge, in the knowledge that the Midland would almost certainly help pay for this. The line was authorised in 1866 and while nominally independent, 4 of the 7 Directors were from the M.S.L.

The M.S.L. was correct in its assumptions and when in 1869 the Sheffield and Midland Joint Committee (S. & M.) was formed to take over the Hyde Junction-Hayfield line, the Midland agreed to accept the unfinished Manchester and Stockport Railway as part of the joint line. At the same time it was agreed to jointly construct the so called "Marple Curve" from Romiley Junction to Bred bury Junction (on the C.L.C. Woodley-Stockport line) to give direct access to Liverpool via the C.L.C.

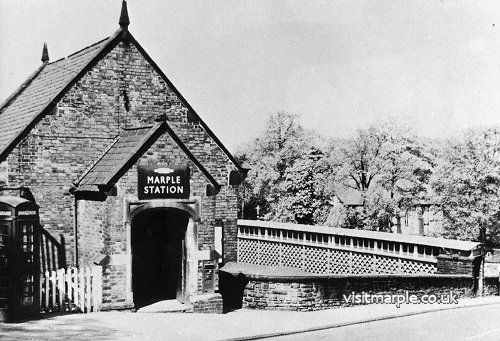

Marple Station Entrance off Station Road.

Thus the Midland was to have a more direct route into Manchester than the circuitous and congested route via Guide Bridge; and a direct route from their main line via Marple to the C. L.C. permitting through running from the South to Stockport and Liverpool, without the need for a detour via Woodley. It was decided that Marple would be the most convenient point for the division and joining of the Manchester and Liverpool portions of St. Pancras expresses; hence the curve to the C.L.C. actually at Romiley, was known as the "Marple Curve". And so the stage was set for Marple, previously a wayside station to assume great importance as a junction for Midland expresses, and interchange point between these expresses and other local services of Midland and M.S.L. It may be asked why Marple was chosen, and not Romiley, which was actually at the junction; Marple station was constricted but there was even less room at Romiley which was on an embankment in a built up area; and of the two Marple was the most important place.

The "Marple Curve" opened early in 1875 for goods on 15th February and for passengers on 1st April. Immediately Liverpool portions detached from or attached to the main Manchester train at Marple began to use it. The sections from Ashburys to Romiley and Brinnington Junction were opened soon after on 17th May for goods and for passengers on 2nd August 1875. In September 1875 Belle Vue and Bredbury stations were opened and Reddish in December. The M.S.L. thereupon started a local service between London Road and Stockport Tiviot Dale, and diverted some of the Marple and Hayfield services via the shorter and quicker route via Bredbury. All Midland main line services were diverted onto the "New Route" via Bredbury, though for some years Midland locals ran from Marple to Guide Bridge.

The Midland was in many respects the most go-ahead railway company of its day, and in 1874 decided to introduce 1st class only Pullman Cars, then only known in America. These Pullman Cars, 60 feet long, were at their time the longest and largest vehicles running in the Country; so long and large in fact that in the course of tests, it was found that they would not pass through Marple South Tunnel, which had to be widened slightly and shortened by some 45 yards at its northern end to its present length of 225 feet, at a cost of £23,000. It is still possible to see traces of this work at the North portal, where a fragment of the old North portal and tunnel wall are still visible. The Midland wasted no time in introducing Pullman cars to their new territories in Lancashire, and Pullman Sleeping Cars for Liverpool began using the "Marple Curve" from the day it opened; Sleeping Cars soon also ran to Manchester, and day-time "Drawing Room" cars to both cities followed.

3. Marple Rebuilt (1875)

To cope with the greatness to be thrust upon it in becoming a main line calling point for Midland Express trains, Marple station had to be extended. These alterations must have been decided on in the early 1870's when the Marple Curve and direct line via Bredbury were under construction, and were probably ready for the new Midland services of 1875. The pressing needs were for longer platforms to accommodate lengthy multi-portioned main line trains, broader platforms, more cover and waiting rooms for passengers changing trains, additional platforms to accommodate terminating and connecting services, and a turntable to turn engines. The great problem at Marple was lack of space, hemmed in as the station was by St. Martins Churchyard on one side, and a steep hillside on the other. At the Northern end of the station the cutting was cut back to the west, and a retaining wall built at its foot, and on the east the cutting was replaced by the present sheer stone retaining wall. Any further expansion in this direction was prevented by St. Martins Churchyard. On the Down side, the platform was slightly lengthened to 538 feet, exclusive of ramps, giving a bay platform about 300 feet long; at the same time it was broadened to about 25 feet throughout. A lofty glass and iron canopy 350 feet long was added to the existing canopy, with a glazed screen to fill the gap at the junction between the two different heights. Thus almost the entire Down side was under cover. On the Up side, the platform was lengthened to 550 feet, exclusive of ramps, and made 33 feet wide at its broadest point.

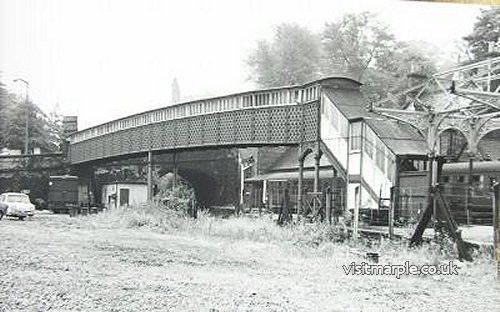

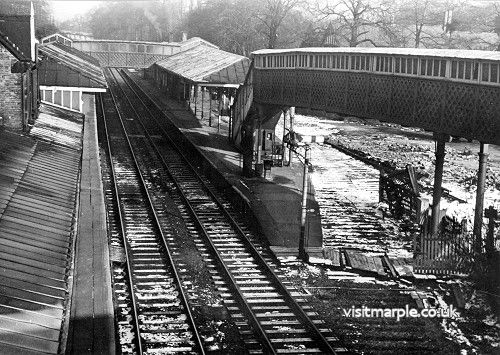

Marple Station on 2 August 1969. From Warwick Burton collection in MLHS Archives.

A loop line was laid behind the Up platform, thus giving 4 platforms in all. Again a canopy was erected slightly shorter than the Down, 315 feet long. A building comprising ladies and general waiting room, with lavatories was erected on the Up platform to cater for those changing trains. A footbridge (which is about the only item from the old station to survive today) linked Up and Down platforms. The addition of a loop line severed direct pedestrian access between Brabyns Brow and the Up platform, so an enormous footbridge 130 feet long was erected linking platform and road. It was originally open, but later roofed over.

The canopy on both platforms was very lofty, about 25 feet high from platform to apex and supported on a double row of cast iron columns, with curious capitals decorated with vaguely mediaeval foliage and "dog tooth" ornament. The weight of the largely wrought iron roof girders was transferred by means of cast iron spandrels with elaborate scroll patterns and roundels. The outer spandrels contained a roundel about 1½ feet across, with a monogram formed of the letters "S.M." (standing for Sheffield and Midland) inter-twined. The roundels were separately cast, and set in lead: One wonders if they were an afterthought. The roof girders had at their extremities notches which supported the timber rafter which carried the pitch pine glazing bars, which in turn supported the large 7½ x 2 foot sheets of clear glass which covered the whole. The roof must have looked magnificent when new, with clean glass and white paintwork.

Three Water Columns were provided on the station: two at the North and serving Down main and bay platform lines, while there was another at the south end of the Up main platform. These were to enable trains to take water en route, especially expresses on the last lap for Liverpool or Manchester, or about to tackle the gruelling climb through the Peak; it also enabled the numerous engines on terminating local trains or Liverpool portions to take water before the next trip. The water was stored in a large cast iron tank high on the cutting wall to the west of the station; the piers which supported it are still visible.

The columns were owned by the Midland, and water was supplied from the M.S.L. owned Peak Forest Canal - at Midland expense. To this day there survives at the North end of St. Martins Road a small brick building which contained the valves of the pipe supplying the tank from the canal, and also a meter to enable the M.S.L. to charge the Midland for the water used. As the Midland paid for the water the drivers of M.S.L. engines were not meant to use the columns, but often did if they could get away with it!

Under the long footbridge from Brabyns Brow was provided a turntable 45 feet in diameter, capable of taking the largest express engines of the day. This was used to turn locomotives arriving on trains from Liverpool, Manchester, or the South, to enable them to run back the right way round.

The entrance to the North Platform at Marple Station taken in the late 1960s

Trains could depart in an Up or Down direction from the Up loop, and Down from the Down bay, but no train could run straight into either loop or bay, and all trains had to reverse to gain access to them. This was because of the railways' dislike of facing points on a passenger line, fearing that the points might move under the train and derail it. Facing points would have been necessary to allow trains to arrive at bay and loop, and so this was not possible; anyway if trains had been able to arrive at the Down bay, they would have had great difficulty in running round, as the locomotive would be trapped at the buffers. Up trains terminating would arrive at the Up main platform, and shunt into the Up loop; the engine would then detach and go on to the turntable, turn round, and run round the train and attach to the coaches standing in the Up loop. It would either remain there ready for departure or propel into the Down bay, in either case then ready for a departure in a Down direction. Any Down trains terminating would follow a similar procedure, though few Down services ever terminated at Marple. Two crossovers, both trailing, were provided; one at the North, the other at the South end of the station; only the South crossover now remains. At the North end of the station were two sidings or headshunts useful for stabling locomotives and putting wagons out of the way when shunting.

The goods yard as before consisted of a siding beside the retaining wall for coal, called the "back road" and one parallel to the Up loop for general merchandise called the "shed road". On this siding a medium sized goods shed was erected to enable merchandise to be unloaded from wagons under cover, and warehoused for delivery.

This was a massive timber structure 30 x 60 feet, with main beams of 9 x 10 inch timbers. At the Southern end was a small office where the documentation work was done. Locomotives were not allowed into the shed, because of the fire risk, nor were they allowed onto the "back road" due to the sharp curvature of the siding; a "barrier" of wagons had therefore to be used in shunting. The goods yard entrance was provided with a gate 15 feet wide and 8 feet high, prefabricated in sections and made up on the site; enough to deter most thieves! The whole layout was controlled by two main signal boxes -Marple North and Marple South; one was just North East of the Brabyns Park over-bridge, and the other just South West of the Brabyns Park over-bridge. The sites of these boxes is still visible from their stone retaining walls in the embankment. There was a third subsidiary box controlling movement into the goods yard only, which was used when required. This was known as the "knob-up" box and was housed under the footbridge steps on the Up platform. So many boxes were needed as there was a strict limit to the distance a box could be from the points it controlled, due to the heavy equipment used in the mid-Victorian era.

The first station master at Marple we have on record was a Mr. Rowbottom, who presided from the mid 1860s onward. By good fortune some of his correspondence survived in the attic of the station, and this casts an interesting light in these early days. One deserves quoting in full:-

"Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway.

"Audit Office, Manchester. June 4th 1875

"(To) Mr. Rowbottom, Marple.

''Dear Sir, I have not yet received your Goods Balance Sheets for the months of March and April though they are much overdue. The absence of these documents is causing us much inconvenience and you really must be good enough to see that they are compiled and forwarded here at once.

Yours truly,

Wm. Pollitt"

(Chief Accountant, M.S.L.R.)

Mr. Rowbottom was in hot water no more than a fortnight later when he received another letter from Mr. Pollitt in which he had "to draw attention to the loose manner in which your clerk replies to the "Clearing House inaccuracies" and to "request you take up with him, and favour me with an explanation"! On a happier note we find Mr. Rowbottom in July 1875 sending a request to the office of the Superintendent of the line at Derby for more luggage barrows for the platforms; the need probably arose with the large number of people now using the station as a result of its new main line status. Incidentally the station master, being in charge of a joint station, was responsible to both companies but was always appointed by the Midland, in view of their more important interest in the station.

4. Train Services 1875

Let us now look at the train services which required such a complicated layout and commodious accommodation. In the October 1875 Bradshaw's Timetable, a total of 34 Up and 32 Down passenger trains are shown calling at Marple station, 66 in all. Of these 20 were M.S.L. trains, the remaining 46 Midland. So it can be seen that the Midland was by far the dominant partner.

The basis of the M.S.L. service was 7 trains each way between Hayfield and London Road, usually via Guide Bridge and taking 3545 minutes to Marple, depending on stops. This was supplemented by 3 trains each way between London Road and Marple only, 2 of which were routed via Bredbury. The best trains of the day were the business trains between London Road and Hayfield, which were routed via Bredbury and omitted calls at Ashburys and Reddish. These are the ancestors of the present morning and evening "expresses": In 1875 they took 25 minutes Down and 27 minutes Up - quite a creditable performance.

Marple Station from the south after closure of goods yard in March 1965.

All M.S.L. trains were 1st, 2nd and 3rd class, but Midland trains were 1st and 3rd only. At that time it was general practice for 3rd class passengers to be only admitted to the painfully slow all stations "Parliamentary" or "Government" trains, so called because the railway companies were compelled to run them and charge a penny a mile fare, under the 1844 Railways Act. All the M.S.L. Marple trains in the October 1875 timetable are shown as "Gov" (Government) trains to indicate that they were of this type. All companies at that time only ran express trains for 1st and 2nd class passengers, and suitable "express" fares were levied. However in 1872 the Midland dropped a bombshell by announcing that henceforth all trains, including the best expresses would convey 3rd class passengers. Other companies were furious and Allport, the Midland General Manager, was accused of "communism" and "democracy" and of wishing to do away with all sorts of institutions. The Midland trains however merely grew at the expense of their competitors, who were soon forced to follow suit and admit the despised 3rd class to express trains, or see them all flocking to the Midland booking offices. Following this, in 1875 the Midland abolished 2nd class altogether, as it was found in practice that most people travelled 1st or 3rd class, and the trouble of providing 2nd class accommodation was not justified by the revenue. All 2nd class carriages were made 3rd class and it was announced that in future all 3rd class carriages would have upholstered seats. Other companies were even more horrified at this revolutionary step, and accused the Midland of "pampering the working classes". The "working classes" however liked such "pampering" and the increase in Midland receipts was staggering. So by October 1875 all Midland trains were 1st and 3rd class only and you would get a good chance of reasonable comfort and upholstered seats, compared with the universal wooden seats of M.S.L. 3rd's. 2nd class lasted nearly 20 years more on the M.S.L. until 1892. What is more, 4 wheeled coaches all but disappeared from the Midland from 1874, the more comfortable 6wheeler becoming the standard, while on Midland express trains bogie coaches were appearing giving an even better ride. 4 wheeled coaches however lasted on M.S.L. trains into the 20th Century.

As has been said, 46 Midland trains called daily at Marple, 24 Up and 22 Down. Of these 7 Up and 6 Down were London expresses which called at Marple. All but one of these services attached or detached a Liverpool portion at Marple, the exception being the 7 a.m. from London Road to St. Pancras and Nottingham, which only had a connection from Stockport at Marple. Many Midland express were non-stop from Marple to Derby and none stopped between Marple and London Road. In fact with 11 Down and 12 Up, there were more Midland trains than M.S.L. between Marple and London Road; the fastest train took a mere 15 minutes, which has never been bettered - even the one non-stop run in 1980 is a minute slower!

A typical Midland express was the 4 p.m. from St. Pancras, which called at Kentish Town (for connections from the City and railways south of the Thames) Wellingborough, Leicester, Trent (where a Nottingham-Manchester Through Carriage was attached) Derby, and then non-stop to Marple, arriving at 8.28 p.m. The train then divided, the front, main portion leaving almost immediately for London Road, where it arrived 4 hours 45 minutes after leaving the capital. As soon as the Manchester portion was away, an engine waiting in the Down bay would then smartly back onto the waiting Liverpool coaches, left behind in the Down main platform and leave for Liverpool about 7 minutes after original arrival. The Liverpool portion conveyed a through Pullman "Drawing Room Car" from St. Pancras, and called at Stockport Tiviot Dale and Warrington Central only, arriving in Liverpool 65 minutes after leaving Marple.

Marple Wharf Junction. BR class 9F 2-10-0 (no. unknown). Unknown goods train.

On the Up, a typical train, though not so fast, had a Liverpool portion which left at 12 noon, and called at Cressington, Sankey, Warrington, Cheadle and Stockport to arrive at Marple first at 1.10 p.m. After a brief call at the Up main platform, the train would draw forward and reverse into the Up loop; the engine would detach and run onto the turntable, to turn in readiness for its return trip to Liverpool.

Meanwhile the main Manchester portion had left London Road at 1 p.m. ran non-stop "via the New Route" and arrived at 1.15 p.m. The express engine detached from its train, ran forward and then back onto the Liverpool portion in the Up loop, drew it forward, and then backed it onto the main Manchester train. The two portions were then coupled up, and left at 1.20 p.m. for St. Pancras calling at most principal and some not so principal stations en route, to arrive at St. Pancras at 6.40 p.m. A "refreshment stop" of 7 minutes was allowed at Trent Junction. Most long distance express trains stopped at a refreshment station en route, for no train in 1875 had buffet or dining cars. Most trains stopped for 10 minutes at Derby, Trent or Leicester to change engines and this gave time to jump out and seize something from the station refreshment room. For the well off, it was possible to send a telegram requesting a luncheon basket (with or without wine) which could be supplied at principal stations for a few shillings. Stops were also necessary for as yet, except in Pullmans, there were no lavatories on trains.

In all 6 Pullman services called at Marple; the 10 a.m. ex St. Pancras conveyed a Pullman for Manchester, which returned on the 4.50 pm. to St. Pancras. The 10.30 a.m. from Liverpool Central returning from St. Pancras to Liverpool at 4 p.m. conveyed "Drawing Room Cars" while the 9.45 p.m. Liverpool-St. Pancras and 12 midnight St. Pancras-Liverpool had sleeping cars, which were in fact converted day coaches. There were as yet no Sleeping Cars to Manchester, but a footnote in the timetable reads "1st class passengers can avail themselves of Sleeping Berths upon payment of a small additional charge, changing into ordinary cars at Marple" - at 4.45 a.m. that is! A strange vision of Victorian businessmen, and perhaps theatre celebrities, stumbling out of Pullman luxury at Marple in the middle of the night to change into the Manchester coaches! These Pullman carriages must have seemed exotic in their rich greenish brown livery, decorated with gold arabesques, their luxurious fittings, and sonorous titles such as "Excelsior", "Britannia" and "Enterprise", though strange to English eyes with their end balconies and open interior saloons.

Many of the St. Pancras trains carried through Nottingham portions, usually attached or detached at Trent or Derby. There were 6 Up and 4 Down services between Manchester and Nottingham, all calling at Marple. On a more mundane level, the Midland also ran 4 stopping services each way between Manchester and Derby; one of the Down trains split at Marple, with one portion going to London Road via Bred bury, the other being sent round via Guide Bridge; another Derby train split for Liverpool and Manchester. In all 8 trains divided and 6 were marshalled up at Marple. To feed its express services, the Midland also ran two connecting trains between Marple and Guide Bridge each way; there were in addition a few trips between Marple and Stockport only. The services Marple enjoyed at this early date are best seen from the table below:-

| To | From | |

| Manchester (M.S.L.) | 7 | 7 |

| London Road (Mid) | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 18 | 19 |

| Stockport Tiviot Dale | 9 | 10 |

| Liverpool | 7 | 7 |

| Derby | 11 | 10 |

| Nottingham | 6 | 4 |

| St. Pancras | 7 | 6 |

On the other hand though through services were in many ways lavish, the timetable was poor in others; there was for instance no M.S.L. service from Marple to Manchester between the 8.50 and 11.10 a.m. and the earliest Down train did not arrive at London Road until 8.10 a.m.

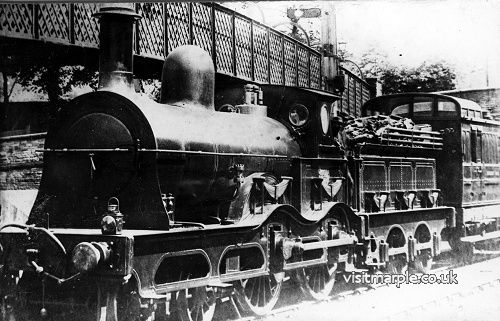

Marple Station in its early days. An MSL train headed by MSL class 6B 4-4-0 No.441 built at Gorton in 1881; the train having arrived from Manchester is in the course of shunting from the up main to up loop ready to depart to Manchester again. Note the footbridge as yet lacks a roof. c. 1885

The Midland express trains of 1875 were hauled by 240s built at Derby Works under Matthew Kirtley in the late 60's, with 6'2" driving wheels; or perhaps on the Liverpool and Derby trains older 'singles' with the 2-2-2 wheel arrangement. Both to our eyes would appear diminutive and picturesque with heavy frames, tall copper capped chimneys and elegant safety valve and dome, but little in the way of a cab to shelter the enginemen. The M.S.L. on its local services used even older and smaller engines, often tanks.

However the passenger service was really only the icing on the cake as far as the Midland was concerned, and the most lucrative revenue lay in goods traffic. Vast tonnages of coal poured across the Peak to fuel the industries of Lancashire and the produce of Manchester and imports through the Port of Liverpool flowed the other way.

Midland goods traffic had developed so rapidly that in the Spring of 1870 a vast new 70-acre goods depot was opened at Ancoats, costing £½ million, a fantastic sum then. Within a few months Midland goods trains were growing longer and heavier, hauled throughout by the ubiquitous Kirtley 0-6-0. On one occasion, as one such locomotive pounded its way south up towards Peak Forest Summit, the blast from its exhaust blew the top of the chimney off! Marple station must have sounded day and night to the rumble of northbound coal and southbound merchandise trains; getting these through without delaying the prestigious passenger expresses must have been a headache to the signalmen, and the loop and bay at Marple must have many times held goods trains to let the St. Pancras expresses past. Such in fact was the flow of freight between Lancashire and the Midlands that severe congestion developed at Derby, which was only relieved when a series of avoiding lines linking Ambergate and Nottingham were created, thus incidentally creating the triangular station at Ambergate, and a new route to Nottingham which passenger trains from Manchester also soon began to use.

5. Manchester Central (1875-88)

However the growing traffic of the Midland added to the equally growing traffic of the M.S.L. resulted in chronic congestion at London Road Station and on its approaches, so that in 1875 the M.S.L. gave the Midland 3 years notice to quit. The Midland had therefore to find itself another terminus in Manchester. As the C. L.C. had the same year obtained powers to build a Manchester Central Station to replace its temporary Cornbrook terminus which eventually became the C.L.C. goods depot. As the Midland was a partner in the C. L.C. it was natural that it should try and gain access to the new station: the only problem was getting a route.

In 1873 the Manchester South District Railway had been authorised to build a line from Manchester to Alderley, but had got nowhere until the Midland seized on the scheme. The line was tailored to suit their own needs, that is for a line from Heaton Mersey Junction, on the C. L.C. Godley-Liverpool line, west of Stockport, to a point on the C. L.C. Manchester-Liverpool line at Throstle Nest Junction.

Originally the line was to have been part of the C.L.C. but the G.N. was "going through one of its periods of wishing to wash its hands of the C. L.C." and refused. The M.S.L. was unsure whether to support the project, so the Midland with characteristic firmness, took it over on its own. The line eventually opened on the first day of 1880.

Meanwhile the great New Manchester Central Station was rising; work had started in 1875. When finished the frontage was only intended to be temporary; it was hoped to build a C. L.C. hotel to form the station frontage, as at St. Pancras but this never matena1~ed and the Midland built their own separate hotel in 1903, at a cost of £1 million. The roof of Manchester Central however was far from temporary; it was a clear span of 210 feet, and 90 feet above rail level, only 30 feet less than St. Pancras. In fact the station is all roof and little else; the side walls are merely to keep out the weather - the main weight, as in a mediaeval cathedral is taken by the ribs of the roof vault, which continue downward into the earth to the foundations. The platforms are in fact built on the tie-beam of the arch, and the space underneath was used as warehousing. The station opened on 1st July 1880, and the Midland now had a first class Manchester terminal, and one that was in many respects the "twin" of St. Pancras. As originally built Central had 7 platforms, but 2 more were later added on the South and were used for locals to Marple, Derby etc.

Steam age commuter rush hour operating at Marple on 20th September 1958. On the left L.N.E.R. L.1 2.6.4.T 67751 calls on the 1729 Manchester London Road - Heyfield, while on the right ex G.C.A.5 4.6.2T 69801 waits to run round in the Up loop after terminating with the 1700 ex London Road. Note the water column, and the wooden goods shed behind the loop. (R. Keeley). (From Marple Rail Trails)

The Midland thereupon transferred all its principal services to Central, gaining access via Stockport Tiviot Dale and the South District Line; at first Liverpool portions were worked via Central but it was soon found quicker to detach and attach at Marple once again or at Stockport in some cases. Marple therefore retained its main line services, though not all now called as they had before Central opened. This relieved pressure on London Road instantly, though for a time some Midland locals continued to run into London Road, and the M.S.L. ran some local services into Central. From 1884 however all Midland trains ran into Central, and M.S.L. trains were confined to London Road.

It is interesting to look at the train services given in Bradshaw August 1887 to see the pattern of service and how it had altered since 1875. The number of weekday trains calling was almost the same - 67 (66 in 1875) with 34 Up and 33 Down. But the composition of the timetable was quite altered. With the Midland having given up running purely local services to London Road, the proportion of M.S.L. trains was much higher, and now M.S.L. trains marginally outnumbered Midland, with 19 in each direction. Of these 18 were to or from London Road, one each way terminating at Guide Bridge. Hayfield had a much more generous service of 10 trains each way, and a few trains now started at New Mills. In addition 7 trains turned round at Marple. Many more services were now routed via Bred bury; there were also more trains in the morning and evening, indicating the growing residential traffic, which is mirrored in the continued building in Marple in the 1870s and 80s, now spreading to Strines Road, Hawk Green and Ley Hey Park.

Fewer Midland trains called at Marple in 1887 than in 1875 -29 as opposed to 46, mainly because the Midland no longer ran its own locals over the S. & M. joint route to London Road, and also because some St. Pancras expresses no longer called at Marple. But in compensation for this, Marple now had services to a second Manchester terminal at Central, 12 trains Up and 8 Down. Some of these were provided by the new local service the Midland ran on the South District line, of which a few were extended beyond Stockport to Marple. Now that Stockport was the effective junction for Liverpool, only one London express was marshalled up at Marple though three continued to divide. But the continued importance of Marple is shown in that many of the St. Pancras expresses still called to give connections to the M.S.L. services, 6 Up and 3 Down in fact; there were also still services to and from Nottingham, 3 each way calling at Marple. 4 services calling at Marple conveyed Pullman cars, including the Up overnight sleeper, which by now conveyed cars for Liverpool and Manchester so that passengers no longer had to stagger half awake in and out of sleeping cars at Marple.

Steam age freight at Marple in 1964. An Up Goods Train of coal empties enters the north end of the station behind a Fowler 4F 0.6.0 43967 built by the Midland Railway at Derby. Note the water column on the Down main platform and the line of the Down bay. (J.R. Hillier). (From Marple Rail Trails)

The best Midland express took 4 hours 40 minutes between Central and St. Pancras, giving a timing of about 4 hours 15 minutes from Marple to St. Pancras. Certain of the St. Pancras expresses ran non-stop between Marple and Central in as little as 22 minutes, Stockport being served by the Liverpool portion. There were four services to and from Liverpool, the fastest, the 3.40 p.m. ex St. Pancras taking only 55 minutes from Marple to Liverpool with 4 stops. An added feature of the 1887 service was the provision of through services between Manchester and Bristol Temple Meads, via Birmingham and Gloucester, 3 of which stopped at Marple in the Down direction only, giving a variety of new destinations directly served from Marple.

6. The "Midland Junction" Line (1889)

But the ever ambitious Midland was still not satisfied with its grip on Lancashire and Cheshire, though by now it had access to Manchester, Stockport, Warrington, Liverpool, Chester and Southport (the C.L.C. had opened a Southport extension in 1884), thus fulfilling the prophetic words of the 1861 agreement with the M.S.L. that the Midland should "run its own trains to Manchester, and every other place in Manchester, in Lancashire or Cheshire or beyond".

In 1889 therefore a short but very important curve known as the Midland Junction was opened linking Ashburys to the L. & Y. line at Ancoats Junction thus providing access to Victoria Station, the largest and busiest of the Manchester stations. Through coaches were introduced between St. Pancras and Manchester Victoria to draw passengers from the Lancashire towns onto the Midland route, and several of these coaches ran through to Bolton and Blackburn: mud in the eye of the L.N.W. which regarded East Lancashire as its own territory by virtue of its through services between Euston, Bolton and Blackburn. The Midland through coaches were detached from the main Liverpool and Manchester train at Marple, to proceed via Reddish, Ashburys and the Midland Junction and most of Pancras expresses stopped once again at Marple for this purpose.

Certain connecting trains were also provided between Marple and Manchester Victoria, providing Marple with services in all to no less than 3 Manchester termini by 4 routes! The curve was also useful in permitting summer holiday expresses and excursions to pass direct from the Midland line to Blackpool, thus further extending the influence of the Midland. In 1862 the Midland had approached no nearer Manchester on its own metals than Ambergate; by 1866 it had arrived; by 1875 it had overrun most of Cheshire and Lancashire, and by 1880 it had a first class terminal at Manchester Central. The Midland Junction Line was the latest move in its campaign to invade the whole North-West, but by no means the last!