VII. Marple By-Passed 1898-1911

1. The Need for the "New Line"

The last decade of the 19th C. had seen a vast increase in the volume of passenger and goods traffic on all the railways of Great Britain; not least on the Midland, and especially on the Main Line via Marple to Manchester and Liverpool. The Midland had arrived late, but had extended its hold by leaps and bounds. Midland passenger and goods trains in the late 90's were much longer, heavier and more frequent than even 10 years before. As a result lines laid down even in the 1860's and 70's were proving inadequate to handle traffic; for instance the section of the Midland Main line from Chinley, where the Hope Valley and Peak lines converged, to Heaton Mersey, where there was the split for Liverpool and Manchester, was becoming increasingly congested; this was particularly serious between New Mills and Stockport, where Midland expresses had to jostle for line space first with G.C. locals as far as Romiley, and then, once on the C. L.C., with another intensive service of passenger and goods trains. Some measure of the growth in traffic can be judged from the fact that in 1887 67 Up and Down trains of both companies had called at Marple; 11 years later in 1898 this had risen to 109 in all on weekdays, and more on Saturdays. In Chapter VI we have seen something of this incredible activity at Marple, such as in the two hours from 8~15 a.m., when 23 Up and Down trains called, with over a dozen shunting moves arising out of trains dividing, terminating or being marshalled up, to say nothing of the goods and non-stop passenger trains which had to find a path through all this. The station, and whole line was working at full pitch, and at Stockport Tiviot Dale congestion was equally bad as at Marple. What is more the Midland route into Manchester from New Mills onward showed its mixed origins (it was in fact built in 8 quite distinct stages by 7 different companies) in numerous sharp connecting curves, switchback gradients and conflicting junctions. This physical unsuitability of the Marple route for express traffic, compounded by congestion, made it increasingly difficult for the Midland to reduce timings to Liverpool and Manchester and so keep up with its competitors, the most recent of which was its erstwhile ally, the G.C. By the late 1890's it was obvious that something had to be done to facilitate the passage of the ever increasing Midland traffic in and out of the North-West. It is said locally that the Midland toyed with the idea of greatly expanding Marple Station to handle their growing passenger traffic, but that this was prevented by the violent opposition of the Hudson Family of Brabyns Hall. This may be so, but it is certain that, had the Midland so wished, such objections could have been over-ridden by compulsory purchase and Act of Parliament. In any case the expansion of Marple would only relieve congestion at the station itself, and could not have given any extra line capacity or provided the desired fast route to Manchester.

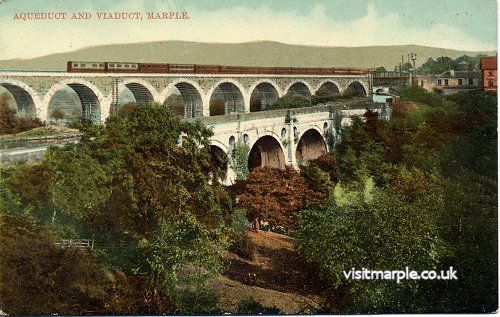

An Up Great Central train of 14 six-wheeled carriages headed by a diminutive tank engine crosses Marple Viaduct. As some of the carriages are in the new G. C. livery of French grey and brown, and some are still in MSL livery, the date must be c. 1900. Note how the viaduct of 1863 dwarfs the Peak Forest Canal Aqueduct of 1800. On the extreme right note the old tall brick Marple Wharf Junction Signal box replaced in 1927 by the box which remained in use until July 1980.

The Midland therefore decided to build a new "cut off" line from just south of New Mills to Heaton Mersey, to be laid out on the most generous lines for high speed running, and to avoid the congestion and junctions of New Mills, Marple, Romiley and Stockport. This route, known as the "new line" was authorised by Act of Parliament in 1898. In addition a large, new junction station was to be built on a relatively level site at Chinley to replace Marple as the connectional and marshalling point for trains to and from Liverpool and Manchester in one direction, and Derby, Sheffield and Buxton in the other. Four tracks were to be extended southward from Gowholes to be continuous from the junction of the Sheffield and Derby routes at Chinley North Junction, to the divergence of the "new" and "Marple" routes at New Mills South Junction, thus providing much needed capacity in what was becoming a bottleneck. At the same time, a large yard was to be built to ease the flow of goods traffic, by providing a convenient marshalling point for traffic from Manchester, Liverpool and the North-West generally for either the Hope Valley route of the Main Line to Derby. This was to be sited at Gowholes, just south of New Mills. All this work was authorised in 1900.

Thus the writing was on the wall for Marple as a Main Line station on the Midland's Manchester Main Line, though it is interesting that in the same year as the "new line" was authorised, the Midland decided to install a larger turntable at Marple, as we have seen, so obviously Marple was to have a continuing if reduced role as a Midland traffic centre.

2. Construction and Opening

Construction of the "new line" began straight away, and the works were on a generous scale, with most cuttings, bridges etc. made wide enough to take four tracks; meanwhile work also began on quadrupling from New Mills south to Chinley, which necessitated the opening out of Bugsworth Tunnel, and the construction of Chinley Station, which was to have five through platforms, and a bay for Hope Valley locals. The largest work however was the construction of the two mile 346 yards long Disley tunnel, which preserves the fine alignments and consistent gradients of the "new line", by going under the Pennine outliers which the Marple route is forced to skirt. Despite its name, over half of the Disley Tunnel is under Marple, running underground about ¼ mile north of the A6 in High Lane; the tunnel emerges as its western portal almost underneath the Macclesfield line just north of High Lane Station.

The construction of the tunnel brought the last great influx of navvies into the district; they were accommodated in temporary villages at New Mills and Wybersley. There was even a tin church erected at Wybersley, where the Midland had an office, later converted into a house. Some idea of the level of activity can be gained from the fact that 300 navvies' children attended local schools.

The method of construction was to drive the tunnel bore from both ends, and from 11 shafts sunk along the line of the tunnel; the miners worked outwards both ways from each shaft, thus giving 24 working faces in all. All but one of these shafts were later used for ventilation, and these are still in use, and visible as large blue brick towers dotted along the line of the tunnel. The Midland bought the land above the tunnel, and though most has been restored to agricultural use, much remains in railway ownership, and to this day boundary markers made of old rails, with the initials "M.R.", can be found along the line of tunnel. To facilitate construction, a standard gauge contractors line was built, using steam locos and a "steam navvy". This ran from exchange sidings just north of High Lane Station to the vicinity of the Andrew Lane Shaft, crossing Windlehurst Road on the level, and the Macclesfield canal by a temporary bridge; the line roughly followed the subterranean course of the tunnel. No traces however are visible as the line was extremely lightly laid and quite ephemeral. On the eastern side of the tunnel however narrow gauge tramways running from the shafts to wharves on the Peak Forest Canal were built; though these too were largely ephemeral, a substantial embankment in Stanley Hall Wood near Disley is said to be the remains of one of these tramways.

The line opened in two sections: first in 1901 the initial section from Heaton Mersey to Cheadle Heath where a large station was erected to serve Stockport, which like Marple, was by-passed by the "new line". The section from Cheadle Heath to New Mills South Junction finally opened to passenger traffic on July 1st 1902. Apart from Cheadle Heath, there was only one intermediate passenger station at Hazel Grove (South), though this never prospered; very few trains stopped, as it was an inconvenience on an express route, and it closed in 1917. The prime function of the line was not local traffic, but a fast cut off line for express passenger and goods trains.

A down limestone train from the Peak hauled by a class 25 diesel rumbles over Marple Viaduct on the evening of 12th August 1979. Note how much the trees have grown since 1900! (Author)

3. Train Services in the Early 20th C.

Immediately the Midland St. Pancras expresses began to use the "new line", and the best Manchester-London timing was reduced to 3 hours 50 minutes, and again in 1904 to 3 hours 35 minutes. Chinley was now the hub of the Midland system in the North-West, a function previously performed by Marple; but Chinley with its greater platform capacity and quadruple track approaches was much better suited for the role. From Chinley lines radiated to Sheffield via the Hope Valley, to Derby and Buxton, to Liverpool via the C. L.C., Manchester Central via the "new line", and via Marple to Stockport, and Manchester Victoria and the L. & Y.; thus connections were available in many directions, and many a local journey involved "change at Chinley". Expresses were also marshalled up and divided at Chinley, for which it was much better suited than Marple. But Marple continued to be served by through portions to and from Manchester Victoria and Blackburn, attached to or detached from the main train at Chinley; softie expresses were also routed via Marple to serve Stockport en route, while most local services continued using the Marple route. Marple was thus no longer on the main line, but still enjoyed quite lavish services to main line destinations by virtue of through coaches.

By 1910 fewer trains in all called at Marple than there had been in the Main Line days of 1898 - 87 on weekdays in 1910 as opposed to 109 in 1898; but the local services provided by the G.C. had increased from a total of 37 in 1898 to 47 in 1910, an increase of about one4hird in only 12 years. Whereas in 1898 the Midland trains calling at Marple outnumbered the G.C. almost 2 to 1, by 1910 the G.C, had a sizeable edge on the Midland. The shift of emphasis from a main line to a suburban station had begun, until today hardly any non-suburban services remain. But the growth in local services reflects the growing size of Marple, and especially the increase in residential traffic to Manchester. Building of new houses continued unabated in the district, and now spread e.g. further along Longhurst Lane in Mellor, up Church Lane and Hibbert Lane in Marple, while Ley Hey Park near the station was developed with fine residences for well-off Manchester businessmen. One reason the Midland continued to stop main line services at Marple was probably to provide such people with services to London and other cities for business purposes, and prevent them making their way to the rival L.N.W. or G.C. routes.

Ley Hey Park, Marple.

The Midland with its longer route to Manchester Central could not hope to compete for local traffic, but they evidently made an attempt to provide a service for the wealthy businessman who started at 10 a.m., with a service arriving at Victoria and another at Central at about that hour, the tatter provided by stopping a fast business service from Sheffield and Buxton at Marple and Stockport only. In all there were 40 weekday services from, and 39 to Manchester, over half running in and out of London Road, the rest, the Midland services, being roughly equally divided between Central and Victoria. The fastest services were often the Victoria trains, which were usually non-stop and taking just over 20 minutes, though one each way called at Bredbury; the fastest G.C. services were the morning and evening "expresses", stopping e.g. at Romiley, Bredbury and Ashburys only, taking 22 minutes. The normal timing was slower - 28 minutes, or thereabouts, via Bredbury, and around 40 minutes via Guide Bridge. Trains to and from Central took anything from 25 to 45 minutes depending on the number of stops.

As has been said, Marple did however continue to be served by Midland main line trains. The overnight St. Pancras sleeping car trains continued to call at Marple, and while the Down train merely called to set down, dividing at Stockport for Liverpool, Manchester and Blackburn, the Up train attached the Blackburn coaches at Marple. Two day-time St. Pancras services each way also conveyed through coaches for Blackburn, which called at Marple, and the 4.2 p.m. ex Victoria was also a through coach for London calling at Marple; in the opposite, Down, direction a Leicester-Victoria through service called at Marple. One interesting service was the 7.45 a.m. ex Liverpool Central which, calling at Garston, West Timperley and Baguley to take up, and Stockport Tiviot Dale, left Marple at 8.47 a.m., ran to Chinley and divided into a fast portion for Sheffield, while the main express ran on via Butterley, Nottingham and Melton Mowbray to St. Pancras, arriving at 1.15 p.m. The 8.45 am. through service from Blackburn, called at Marple at 10.6 a.m., was attached to the main train at Chinley, and then ran non-stop to St. Pancras, which was reached at 1.50 p.m., - 3 hours 51 minutes from Marple. In all there were 5 services to and 3 from St. Pancras. Certain cross-country trains were also routed via Marple, the most remarkable of which was the 11.30 a.m. from Liverpool Central, which called at Warrington, reversed in Manchester Central, then calling at Didsbury (to take up only) and Stockport, left Marple at 12.52 p.m., before running to Derby, one portion being attached to the Newcastle-Bristol Restaurant Car Express~ calling only at Birmingham New Street and Gloucester; the other coaches ran forward via Nottingham and Melton Mowbray on to the single track Midland and Great Northern Joint line via South Lynn and Melton Constable, calling at such unlikely places as North Walsham (Town) deep in the Broads, and coming into the line's terminus at Yarmouth Beach, where the coaches were now shunted onto the rear of a stopping train to Lowestoft, which was reached at 8.3 p.m. Surely the most exotic through coach service ever calling at Marple, taking, incidentally, over 81A hours to get from West Coast at Liverpool to East Coast at Lowestoft! Up to 1907 the Midland had run a Southport Chapel Street (C. L.C.) - St. Pancras through coach via Marple; and in the summer there were even more such through coaches and trains to holiday resorts, notably from the Midlands and Sheffield to Southport and Blackpool, and from the North West to Cromer, Yarmouth, Lowestoft and even the Kent Coast.

Many Midland local services between Buxton, Millers Dale, Derby or Sheffield and Manchester Central continued to run via Marple, though quite a few went via Cheadle Heath. Some locals calling at Marple started or terminated at Chinley, as did those trains to and from Victoria which were not through coaches, to give connections with the main line. In all 21 Up and 17 Down Midland trains called at Marple on a weekday, several of which were shuttle journeys between Marple and Stockport.

As yet on Midland services calling at Marple gas lighting and compartment coaches were the rule, for electric lighting and corridor coaches were found only on the latest main line trains, though lavatories and steam heating were becoming commoner even on local trains. In contrast G.C. stock was still very archaic with 4 and 6 wheelers, where the Midland had 6 wheelers and bogie carriages. On its best Main line trains the Midland was beginning to use its famous 440 "Compound" Locomotives; these were larger than anything hitherto seen on the Midland, which always had a "small engine" policy. These "Compounds" must have occasionally been seen at Marple, especially on Sunday Main line diversions, but the bulk of Midland trains would have been hauled by older ex-express engines, such as the "Spinners"; in some cases the engines were antiques of 30, 40 even 50 years old, but lovingly maintained and polished.

The opening of the "New Line" via Cheadle Heath, and the accompanying expansion of passenger and goods facilities at Chinley and Gowholes respectively allowed the Midland to compete much more effectively for traffic in the North West, particularly Manchester, so that by 1910 the Midland's hold had greatly increased on what it had been only 10 years before. Marple might be by-passed by the Main line, but it retained quite a lavish provision of through services, and had access to all the rest of the Midland's express trains via connections at Chinley. And the Marple route was still an important freight link to the principal Midland goods depot in Manchester at Ancoats, and also the L. & Y. system. In fact in the early years of the 2OthC. traffic on the Marple route continued to increase to such an extent that congestion got worse rather than better. It was a requirement then (as it still is) of the "Absolute Block" System of Signalling operating on the route that only one train must be in a block section at once (a block section being the length of line between two signal boxes); it follows therefore that the more signal boxes there are, the more trains that can use a line at once. In addition the 1860's and 70's signalling was badly out of date. In the early years of the 2OthC. therefore the Midland re-signalled the Marple area. First Romiley signal box was rebuilt in 1899. Then, to shorten sections, new signal boxes were provided at "Marple Goyt Viaduct" between Marple and Strines (and just south of the Viaduct itself) in 1904, and at "Oakwood" between Romiley and Marple Wharf in 1907.

Marple Station with signal box in 1980. provided by Paul Mallett.

At Marple a new signal box, in use until July 1980, was erected in 1905 at the north end of the Up platform. This replaced Marple Station North, South and Goods Yard Boxes, greatly facilitating station working, as all was under the control of one man, instead of two or three as previously. As however the points for the 1898 turntable were now too far from the new Marple Box to be operated by the signalman, a ground frame was provided at these points and were operated when required with permission from the Signalman. To compensate for the reduction in the number of sections and thereby capacity at Marple, "outer home" signals were provided, which allowed the signalman to accept another train into his section while there was already a train in the station. Another device was to install "inner" and "outer" distant signals, which allowed the signalman two chances of giving a train a clear run: that is if a train passed Marple's outer distant at caution, due to the presence of another train ahead it would commence braking; if however the train ahead then moved on, the signalman could clear the inner distant, to indicate to the driver that he could proceed at full speed. This was an invaluable aid to the flow of traffic in an area like Marple where sections were short. These signalling devices were characteristic of the Midland and remained in use until very recently. At the same time the Midland erected new lower quadrant signals (i.e. ones which show "proceed" when lowered at an angle of 45º all along the route. They were mounted on elegant wooden posts with "gothic" finials, some of which survived until re-signalling in 1980. The electrical block bells and indicators of solid brass and polished mahogany installed in the 1900's lasted until a few years ago in most boxes in the area. Marple Wharf Box was not however rebuilt until 1927 by the L.M.S., but following Midland designs.

In many ways the year 1910 marked the high water mark of railways throughout Great Britain, not least for both Midland and Great Central. Marple's Main line heyday of the 1890's may have passed, but such had been the growth of traffic, especially suburban passenger and goods in the early years of the 2Oth C. that in 1910 Marple by-passed was probably not a great deal less busy than it had been in its Main line days; and as more and more people came to live in Marple, continued growth seemed assured. Coaching stock might seem archaic to our eyes, but it was well cleaned and maintained, at least on the Midland, and, like the locomotives, decked in colourful liveries. Stations were still beautifully kept, and staff to help passengers and manhandle merchandise were plentiful; and while wages were low and hours long, the real purchasing power of the working man had risen over the previous 30 or 40 years.

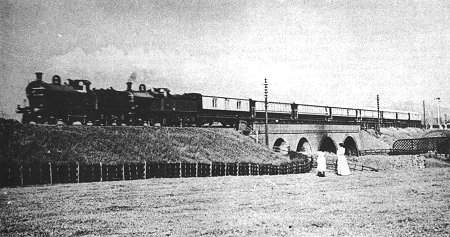

The Royal Train conveying King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, passing Bredbury Station (extreme right) on 12th July, 1905. The King and Queen were paying a state visit to Sheffield and Manchester, and the Royal Train is en route from London (St. Pancras), via Sheffield and the Dore and Chinley Line, to Manchester (Victoria), where the L.N.W. took over for the final leg to Huyton (near Liverpool). The Royal Party detrained here to spend the night at Knowsley Hall as guests of Lord Derby. The L.N.W. Royal Coaches are double headed by 2 Midland Railway 4.4.0 express locomotives built at Derby, designed by S.W. Johnson. This train would have passed through Marple Station a few minutes before the photograph was taken (Photograph supplied by J.N. Wood).

Heyday it might have been, but in truth it was an Indian Summer; the end of the confident Victorian era, the beginning of the end of the age of steam, gas, iron and coal. The "New Line" of 1902 was almost the last piece of railway expansion in the district, and the non-stop, hectic construction of the previous 70 years slowly came to a halt. For in 1910 the storm clouds were just appearing for England and for the old Europe, as well as for the Railways.

The interior of Marple Signalbox on 12th September 1978. Note the fine Midland lever frame; the block instruments are however modern. This box closed on Sunday 27th July 1980. (Author)