III. Enter the Midland. 1845-1872

1. The Midland Attempts to Reach Manchester (1845-56)

We must now return to 1845 and the Railway Mania to trace the steps by which the Midland came to play such an important part in the railways of Marple. Remember the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway? (M.B.M. & M.J.). The line was projected in the 'Railway Mania 1845' as a means of providing the M. & B. with an outlet to the south independent of the Grand Junction Railway route via Crewe. Unfortunately as soon as the M.B.M. & M.J. got its Act in 1846, its most enthusiastic supporter, the M. & B., amalgamated with the Grand Junction and other railways to form the L.N.W. and the L.N.W. was not interested in a route to London competing with its own. This, combined with the post Mania slump, made it very difficult to actually obtain finances for the line, and all that was eventually opened was an 11½ mile branch from Ambergate to Rowsley - a short line for such a long title! The line was originally worked by the Midland, but unfortunately the L.N.W. had inherited from the M. & B. a considerable number of shares in the line, so that in 1852 the Midland was forced to agree to a joint Midland L.N.W. lease of the line for 19 years. The Midland was chiefly interested in the line as a springboard for Manchester; the L.N.W.'s only interest in the line was to prevent it being used as such. (Eventually however when the Midland did reach Manchester, the L.N.W. gave up its interest in the line and the M.B.M. & M.J. became part of the Midland in 1871). Meanwhile the Midland was unable to do much on this front for some years, as it was dependent on the L.N.W. for access to London via Rugby; and both companies were pre-occupied with the newly built Great Northern Railway. In an attempt to strangle this new company which had broken the L.N.W.'s monopoly of all traffic north out of London, the L.N.W. formed an alliance with the M.S.L., L. & Y. and Midland.

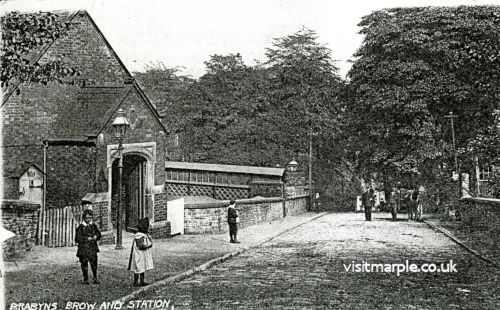

A view of Marple Station on Brabyns Brow, from Marple Local History Society Archives.

1854 however saw the promotion of a nominally local railway, the Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge (S.D. & W.B.) which we have already met, causing agitation to the M.S.L., by invading its "territory". But this line also offended the Midland, as it followed closely the projected course of the M.B.M. & M.J. and was rightly seen as an L.N.W. attempt to occupy the territory in between, and so block their route to Manchester; for this nominally local line was in fact heavily subsidised by the L.N.W.

The Midland were however unable to put up parliamentary opposition as they had no "locus standi" in the matter. The L.N.W. assured both Midland and M.S.L. that it had no intention of using the line to reach Buxton; in 1856 however the Midland suggested an extension from Rowsley to Buxton to meet with an extension of the S.D. & W.B. and thus permit through running between Derby and Manchester. The L.N.W. refused to consider through traffic, and would only agree to accommodate local traffic, which clearly showed their intention of blocking the Midland. Meanwhile the L.N.W. broke its assurances and secretly promoted a nominally local extension of the S.D. & W.B. to Buxton. The proposed course was extremely sinuous and heavily graded and in this the Midland rightly saw the line as designed to prevent any fast through running, if the Midland ever should reach Buxton.

By now both the M.S.L. and Midland were so frustrated by the L.N.W.'s double dealing that they broke up their alliance with the L.N.W. The M.S.L. promptly allied with the G.N. The L.N.W. was initially furious at the G.N./M.S.L. alliance which brought a competitive route from London into Manchester; but in the end they decided to make the best of a bad job and concluded an illegal agreement with the G.N., M.S.L. and L. & Y. to prevent the Midland reaching or sending any traffic to Manchester, an attempt which failed, due to the boundless energy of the Midland.

2. The Midland Advance from Rowsley (1857-65)

The Midland was however by now free from the L.N.W. grip for access to London, having in 1857 concluded an agreement with the G.N. for Midland trains to run into King's Cross. Caution was therefore thrown to the winds and the Midland promoted a Bill for a line from Rowsley to Buxton, and requested running powers over the S.D. & W.B. and its Buxton extension to Manchester. The L.N.W. tried to scotch this by proposing a direct route from Whaley Bridge to Buxton, or alternatively by leasing the C. & H.P. and making it into a through route to block the Midland. These attempts however failed, and the Act for the Rowsley and Buxton line was passed in 1860 but the L.N.W. made it quite clear it would not allow any through traffic to pass via Buxton.

The Midland was not put off and decided on an independent line to Manchester, whatever the cost, and commenced surveying. One day in the Autumn of 1861 took place a chance meeting which was to alter the course of railway history, and have a profound effect on Marple. The Chairman, Deputy Chairman and General Manager of the Midland were driving through the countryside, examining the course of various proposed routes to Manchester. Suddenly in a narrow lane they came face to face with a party of M.S.L. Directors and Officers in a dog cart. "And what are you doing here?" the M.S.L. party good naturedly demanded. The two parties then spent the rest of the day together, and in the course of conversation it was suggested by an M.S.L. Director that the Midland might be able to use the M.S.L. and M.N.M. & H.J. line to reach Manchester. This proposal was eagerly seized by the Midland men who offered terms the M.S.L. could not refuse. Thus the M.S.L. double-crossed its allies the L.N.W. & G.N. For at that very time the M.S.L. was still smarting from the L.N.W. invasion of its territory via the S.D. & W.B. and was at loggerheads with the G.N. over some other issue in South Yorkshire; in addition it had no wish to see yet another competing line in their territory between Manchester and Buxton.

A ghostly image of Marple Station in its heyday, from Marple Local History Society Archives.

A formal agreement was reached later the same year, and in 1862 the Midland's Rowsley and Buxton Extension Line was promoted to run from Blackwell Mill (near Miller's Dale) on the Rowsley and Buxton line under construction, to New Mills on the M.N.M. & H.J. with powers that "the Midland should run its own trains over the railways of the Sheffield Co. (i.e. M.S.L.) to or from Manchester, and every other place in Manchester, in Lancashire, or Cheshire, or beyond". Prophetic words!

The L.N.W. in panic offered the Midland "facilities" over their Buxton line, but the Midland counsel at the parliamentary hearing retorted that the Midland knew what "facilities" were when the L.N.W. was concerned. The L.N.W. had what it considered a serious objection to the line, in the plight of gouty patients coming to Buxton to take the waters for the easing of their complaint and forced to change at Millers Dale by reason of the new Midland Main Line's avoidance of Buxton. But the line enjoyed the support of every landowner on its route, Manchester Corporation and numerous manufacturers and merchants; while the City's Chamber of Commerce spoke warmly of the improvement in communication with the Midlands such a line would bring. Notwithstanding the alleged plight of gouty patients, the line was authorised by Parliament, and work began.

Meanwhile work had been progressing since 1860 on the Rowsley and Buxton line, which presented innumerable difficulties to construction through the narrow gorge of the Wye from Bakewell onwards, with numerous tunnels, viaducts as well as underground streams and caverns to contend with, while the ducal estates of Haddon and Chatsworth had to be protected from disturbance. The line was eventually finished, and the official opening to Buxton took place on 30th May 1863. A special train ran from Derby followed by a luncheon in Buxton at 2 p.m. for the Midland Directors, the Duke of Devonshire, etc. According to the "Stockport Advertiser", congratulatory speeches were made, and it was especially remarked that the line was opened on the day originally fixed - a rare thing on railways. Not to be outdone, the S.D. & W.B. ran an official "opening" train from Manchester and gave a luncheon at 3 p.m. in Buxton. But while the Midland line opened for traffic on 1st June 1863 the S.D. & W.B. extension to Buxton was not actually ready for public traffic until 15th June 1864! The two companies had separate stations at Buxton, glaring at each other across a common forecourt.

3. The Midland Enters Manchester and Marple! (1866-8)

Meanwhile work was proceeding apace on the extension to New Mills, despite problems encountered with the Peak underground rivers, problems so great that no contractor could be found to make Dove Holes Tunnel, and the Midland were forced to do it themselves. The line was ready by October 1866, and Midland goods trains were passing over it and through Marple to Manchester. However the autumn of 1866 was marked by torrential rains, and a remarkable landslip occurred on the Midland's new line at Bugsworth; all of a sudden 6 acres of land slipped off the hillside, and the railway viaduct, formerly curved, became straight as a result of the earth movements. Services were suspended, and the Midland immediately set about to restore the line; for 10 weeks 400 men worked day and night to construct a viaduct of timber, creating a deviation about ½ mile long.

The slip took place just East of Bugsworth station and the new alignment was carried North of the station, instead of to the South as previously, so that the station was turned back to front. Later on in 1885 a new embankment was constructed and the original masonry and the temporary timber viaducts were removed.

Marple Wharf Junction. BR 9F 2-10-0 no. 92130.

The line re-opened on 1st February 1867, this time for goods and passenger services. The Midland immediately started running a series of express trains from London King's Cross to Manchester London Road. The L.N.W. and G.N. were forced to countenance yet another competitor for London-Manchester traffic actually within their respective terminals at Manchester and London. The Midland had at last reached Manchester, despite all these companies had done to prevent it, and the Marple and New Mills line was the last but one link in this chain.

Finally on 1st October 1868 the Midland opened their extension to London St. Pancras, which gave approach to the capital independent of the G.N. or L.N.W. The Midland commenced running two expresses each way between London St. Pancras and Manchester London Road, taking 5 hours only, which was then the timing of the G.N./M.S.L. and L.N.W. best expresses, despite having a much more difficult route through the Peak. A formidable new competitor had now arrived on the Manchester scene, and great must have been the excitement at stations such as Marple, as the Midland 5 hour trains swept through, drawn by a fine Kirtley 2-2-2 express engine, in the rich green livery then favoured by the Midland with a string of magnificent crimson lake coaches behind, so different from the dowdy M.S.L. stopping trains. At the same time the Midland began running local services from Manchester to Buxton and Derby, which supplemented the M.S.L. trains calling at Marple, and gave a direct outlet to the South. This however was merely the beginning of the Midland invasion of Lancashire and Cheshire!

4. The Sheffield and Midland Joint Committee (1868-72)

You will recall that the line from Hyde Junction to Hayfield had been built to take double track throughout but as each section had opened, it was with single track only.

The arrival of the Midland made doubling of the line imperative, and the section from New Mills to Hyde Junction was doubled probably some time in 1866. At the same time additional platforms were provided at all stations en route, though at first they would have had very little in the way of buildings. The wooden shelters which were probably erected at this time survived until quite recently at Hyde Junction, Woodley, Strines and New Mills and it is probable that at first Marple had such a building on the Up platform.

The M.S.L. being an impecunious company decided that as the Midland were gaining such benefits from the New Mills-Hyde Junction line, they might as well share the cost of maintenance and running. The Midland agreed, and an Act was passed on 24th June 1869 vesting the line from Hyde Junction to Hayfield in the "Sheffield and Midland Joint Committee" (S. & M.) which had equal numbers of Board Members from the M.S.L. and Midland. This committee left numerous traces until quite recently; the monogram in the ironwork of Marple's roof were in fact the letters "S.M." entwined and until very recently there was a bench at Romiley with the words "S. & M.J.C." carved on the back. This is now in the National Railway Museum at York.

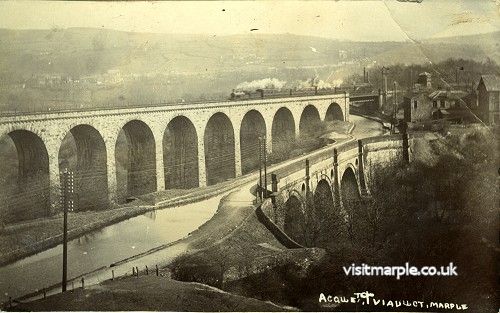

Marple Aqueduct and Viaduct with the Queens Hotel and Aqueduct Mill visible.

There were as yet no goods or coal depots on the line from Hyde Junction to Hayfield, which is surprising as the early railways usually found goods traffic more profitable than passengers. Perhaps the M.S.L. feared to damage the goods carryings on their Peak Forest Canal, or perhaps they hoped the Midland would help pay for them when they started using the line.

As might be expected the Midland soon requested that the S. & M. stations should have goods depots, and the M.S.L. agreed to their provision at Woodley, Romiley, Marple, Strines and Hayfield in 1870 and subsequently at Hyde and Birch Vale. Coal traffic was dealt with at these stations from 1870 and general merchandise followed in 1872. There was never a S. & M. goods depot at New Mills but the Midland built their own at New Mills East, and presumably the M.S.L. sent its traffic there.

5. Marple Station in 1872

By now Marple Station had grown considerably from the single platformed affair of 1865. By 1872 on the Down side a bay platform had been added, much in the same position as the later bay; the Down platform had been lengthened considerably to about 530 feet, not much shorter than its final length though it was very much narrower. The bay was used to stable trains terminating at Marple before they departed again for Manchester, or to shunt goods trains out of the way. The Up platform was much shorter (c.350 feet) and extended from Brabyns Brow to the footbridge carrying Seven Stiles footpath over the line. On it there was a large set of waiting rooms, probably of wood, and a staircase at right angles to the line led up to Brabyns Brow. The Down platform buildings were unchanged from their original form of 1865.

The goods yard was smaller than it later became, and contained two sidings; one against the retaining wall of St. Martins Churchyard, for coal and one behind the Up platforms for merchandise and livestock. The Northern end of the station was not hemmed around with retaining walls as yet, but a sloping embankment divided the station from Brabyns Park and on this embankment was perched the station signal box which controlled the primitive signalling of the day, and controlled the points, included those of the trailing crossover from Up to Down line in front of the signal box.

The opening of a goods depot would have been a great boon to the district; the price of coal, a basic necessity of every home and industry, would have dropped several shillings a ton, as it could now be brought direct from the pits of the Midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire without the need for road haulage from the nearest railhead or slow canal transport. The coal merchants therefore transferred their businesses to the railway goods yards. Local cotton mills found obtaining raw cotton, and dispatching finished products greatly speeded up by the railway, and themselves better placed, to compete with the Mills of adjoining rail-served towns.

Agriculture was stimulated by the ease with which the new machinery of the 19th Century and all manner of general merchandise could reach the district; livestock no longer had to be driven to Market, losing weight and condition all the way, but could be conveyed in a few hours by train. Postal services were greatly speeded up, as mail could now reach Marple within a day or two from most parts of the Kingdom. The Railway also facilitated the conveyance of all kinds of merchandise to the district, which contributed to the rising standards of living of the 19th Century. To deliver these goods, the railway usually appointed existing carters as their agents, and so the whole transport system of the district came to revolve around the station. In Marple the canal continued to carry limited commercial traffic up until the 2nd World War, but it was gradually dwindling away.

The 1875 ironwork of the canopies of Marple station shortly before demolition. Note that the large roundel in the canopy contains the intertwined letters "S & M" (here seen in reverse), standing for "Sheffield and Midland".