THE IRON BRIDGE IN BRABYNS PARK

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PARK, THE IRON BRIDGE & THE PEOPLE INVOLVED IN ITS CONSTRUCTION

By Mark Whittaker and Peter Clarke (November 2006)

This is an on-line version of a booklet first prepared in March 2003 for submission with the application for an HLF Project Planning Grant towards the cost of investigative works associated with restoration of the Iron Bridge. It was updated in November 2006 for inclusion with the main grant application.

Text is unchanged but additional images have been added during migration to the new web site.

Introduction

The Marple Website, run by local history enthusiasts Mark Whittaker and Peter Clarke, began campaigning for the restoration of the Iron Bridge in Brabyns Park in June 2001.

Marple Local History Society joined the web site team in their campaign during 2002 and a group was formed with Stockport Council to find ways to fund restoration of the bridge. Growing support for the campaign was demonstrated by the collection of over 2000 signatures and more than 120 individual letters of support.

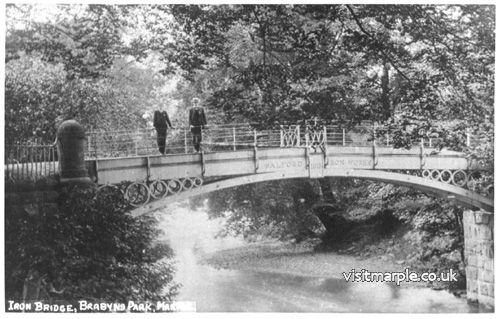

A view across the Iron Bridge in Brabyns Park with the gate still intact.

In August 2003 the Group made a successful application to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) and received a Project Planning Grant of £30,100 to establish what was wrong with the bridge and to develop a scheme suitable for the bridge's strengthening and repair.

The work covered by the Project Planning Grant was successfully completed in March 2006 and at the time of writing the Group is preparing an application to the HLF for a second grant, which, if also successful, will provide up to 90% of the funding needed to restore the bridge to its former glory.

This booklet has been prepared to bring together the information that has been gathered during research into the bridge's history, to provide an insight into the background of the people who were involved in its construction, and to place all these in the context of Brabyns Park as a whole.

It is hoped that the booklet will be updated as the restoration project progresses and also if anything further of significance is learnt about the bridge, or those who were instrumental in its creation.

Brabyns Estate

Thomas Lowe, of Lower Marple, described as an ancient freeholder in the registers of All Saints' parish church, is the first recorded owner of the land that later became the Brabyns Estate. Low Marple is the name that has been given to the area alongside the river Goyt, on the Marple side, since these early times.

Thomas died in 1667 leaving goods and chattels to the value of £464 to his nephew, Francis Lowe, Rector of Taxal. This included bags of gold to the value of £338! The estates obviously remained with the Lowe family for many years, as in the early 1740s a survey of all the land in Marple recorded John Lowe, gentleman of Marple Bridge, as the owner of forty acres.

John's only daughter and heiress, Elizabeth Lowe, married Doctor Henry Brabin, a surgeon practising in Stockport, in 1741. After her father's death, in 1749, Elizabeth inherited the estate. Henry Brabin built a grand Georgian house on the land, facing down the valley away from the main road with the entrance to the drive through lodges on Brabyns Brow.

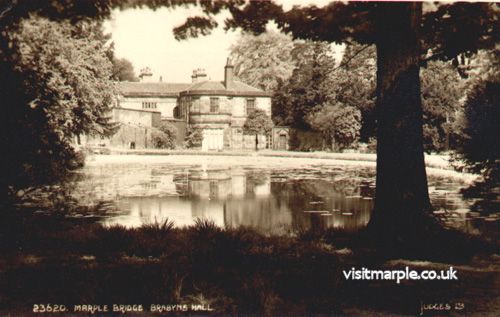

Rear view of Brabyns Hall from across the pond, which is still there.

Henry Brabin died in 1750. Elizabeth, who was to outlive him by nearly forty years, never remarried. Their only surviving child, also Elizabeth, married Nathaniel Bradshaw Isherwood of Marple Hall in 1765; however, she was not to be mistress at Marple Hall for very long as she was widowed only four months later and did not inherit from her husband.

In 1777 the younger Elizabeth married again, to Mr Edward Whitehead, a solicitor of Bolton and the couple later moved to Soho in London. In 1783 the Brabyns estate was advertised for lease. It is likely that around this time Elizabeth moved to live with her daughter and son-in-law in Soho, and she died there in 1788.

Edward Whitehead outlived his wife and inherited the estate from her. According to land tax records the estate was still owned by Edward in 1799, but tenanted by a Mr. Peter Fogg. In 1800 Edward Whitehead sold the estate to Nathaniel Wright, a gentleman of Poynton.

Nathaniel Wright was a wealthy coal miner and landowner. He made many improvements and alterations to the estate, including extensions to Brabyns Hall and erection of the Iron Bridge in 1813, creating a carriageway onto the estate from the village of Compstall.

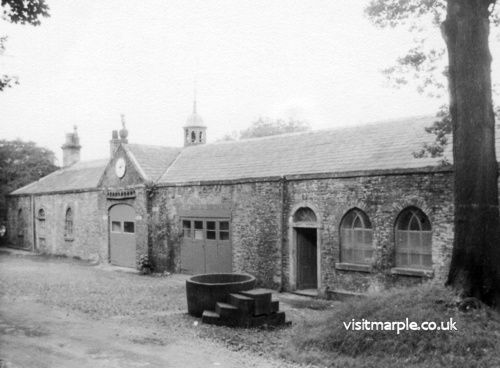

The stables in Brabyns Estate demolished in the 1970s

Nathaniel Wright's son, John, was born in 1800, the year the family moved to Marple. When Nathaniel died, in 1818, his estates and businesses were left in trust to John and his heirs, or for Ann Hudson, his married niece.

When John came into his inheritance, at the age of twenty-four, he sold off much of his father's business interests and land in other areas and the proceeds were used to purchase more land around the Marple estate. He never married and immersed himself in local affairs, eventually becoming a Justice for the Peace and one of five Magistrates officiating for the Stockport Division.

When John died, in 1866, the estates passed to Ann Hudson, his cousin. After the death of her husband, in 1868, Ann took up residence in Brabyns Hall, accompanied by her daughter, Maria Ann, and her recently orphaned granddaughter, Fanny Marion. The family were very wealthy and lived in considerable style, but also played an active role in local affairs and even built a new church on Brabyns Brow.

Ann Hudson died in 1884 and her daughter Maria Ann, who was unmarried, inherited the estate. Fanny Marion, who also never married, remained living at the Hall too and inherited following Maria Ann's death in 1906.

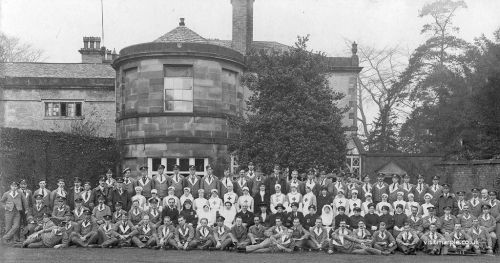

Fanny Hudson continued the family tradition of involvement with the local community and during the First World War the Hall became an Auxiliary Hospital and Convalescent Home for wounded soldiers.

A large crowd of casualties and staff with Miss Hudson at Christmas 1918

Fanny died, in 1941, at the age of ninety years. In her will she instructed that Marple, Romiley and Bredbury Councils were to have the first chance to buy her property. With the help of Cheshire County Council the estate was purchased and opened as a public park in 1949. Sadly, plans to turn the Hall into an Art Gallery, Museum, Reference Library or Assembly Hall, as a memorial to the local men who died in the war, were to fail, and it was demolished in 1952.

Today the park itself is owned by Stockport Metropolitan Council, and is a thriving asset, extensively used and highly valued by the people of Marple.

The Iron Bridge

The world's first and internationally most famous iron bridge is that which gives its name to the town of Ironbridge in the south of Telford, Shropshire. It was built across the River Severn in 1779 by local ironmaster Abraham Darby III to demonstrate the quality of the iron produced by the process his grandfather invented to smelt iron using coal, rather than coke. The Iron Bridge has become an accepted symbol of the Industrial Revolution and is the central feature of the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site.

The Ironbridge in Telford, Shropshire

Marple's iron bridge, in Brabyns Park, although somewhat more modest than this first amongst the world's bridges of iron, is, nevertheless, a unique structure of national importance. One of very few cast iron bridges surviving from this period, it is already grade II listed. The Georgian Group - a society with particular interest in the Georgian period - have applied for it to be upgraded to II star, which will place it on the National Buildings at Risk Register.

A classic image of the Iron Bridge in Brabyns Park before its decline.

The bridge was built in 1813 for the then owner of the Brabyns Estate, Nathaniel Wright. Its purpose was as a carriage bridge across the River Goyt, creating access to Wright's estate from the village of Compstall. It was constructed of cast iron by the Salford Iron Works, an Iron Foundry owned by Messrs. Bateman and Sherratt that was established in the latter part of the 18th century.

It is uncertain who designed the Brabyns Bridge, although it's possible that William Sherratt himself may have been responsible. He was an engineer of considerable talent and reputation and it is easy to imagine his basing the plans on the innovative designs of Thomas Telford, whose iron bridge at Cound Arbour was built in 1797, and that of Thomas Wilson at Tickford, built in 1810. Both these bridges, although different in scale, bear remarkable similarities to the one constructed for Wright across the River Goyt.

Tickford Bridge (1810), Cound Arbour Bridge (1797), Brabyns Bridge (1813)

The book 'The Iron Bridge' written by Neil Cossons and Barrie Trinder in 1979 mentions Marple's bridge both within the text and also within a checklist of 'all known bridges to have been built before 1800, and those constructed between 1800 and 1830 which are well documented, or of particular historical importance'. The checklist indicates that only three such bridges were built during 1813, one in Hungary and another, in Clare, Suffolk, which is completely different in design from the one built for Wright. This checklist also shows that Marple's bridge was the first of its kind constructed in the North West.

The Brabyns Bridge, which was in constant daily use, survived the years since its construction with a minimum of maintenance, until a structural assessment carried out in 1991 identified that it was in a dangerous condition. As a result of these findings a 'Bailey Bridge' was erected across it as a temporary measure, until funds could be found to pay for the restoration work necessary.

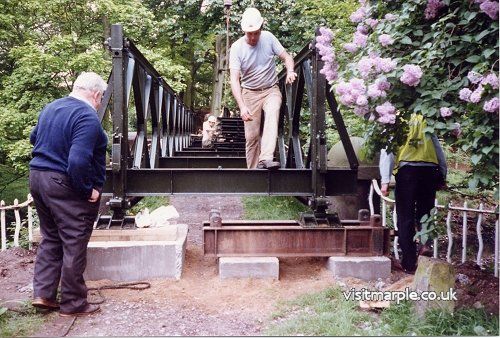

The Bailey Bridge is installed in July 1992. Reg Walters (left), owner of Iron Bridge Cottage, keeps a close watch on the workers.

Unfortunately this action was not without its own misfortune as the crane used to erect the Bailey Bridge accidentally demolished another listed bridge in the park. This was a stone one, built in 1804, known as the Scroll Bridge. Much of the stonework for Scroll Bridge has been recovered from various locations around the borough and it is due to be rebuilt in 2007.

Sadly, the money for repairs to the Iron Bridge has not yet been found, leading to the campaign begun in 2001. With the formation of the Iron Bridge Restoration Project Group in 2002, the prospects of the bridge's survival are improving and it is hoped that a full restoration will be possible.

Nathaniel Wright

Nathaniel Wright was born in 1760 but information about him is sketchy before his name first appeared in connection with Poynton Collieries in 1793. This was in a draft lease between Sir George Warren, Nathaniel Wright of Poynton, Gentleman, and Mathew Pickford of Poynton, Waggoner.

By 1794 Wright had his first pit at Poynton and the coal he extracted from it was carried to coal yards in Stockport and Macclesfield. In the same year he was also negotiating to lease mines at Norbury and Middlewood. In June 1795 another lease was agreed between Wright and Thomas Peter Legh for three more mines in the area, and Wright's empire was expanding rapidly.

It was in 1795 that Wright installed a new pumping engine at his collieries; this was built by Bateman & Sherratt and is the first recorded link between Wright and the owners of the Salford Iron Works.

Wright was associated with some of the most influential engineers and entrepreneurs involved with mining and canals at the end of the 18th century. The Legh of Lyme papers at John Rylands library contain letters written by Wright and also copies of letters from Benjamin Outram, Robert Fulton and Matthew Fletcher relating to Wright's schemes.

One of the oldest images of the Iron Bridge and cottage c1890, but some time after Wright's era.

At one stage Wright was proposing to build his own canal from Norbury to Stockport. The line was surveyed and laid out by Fulton and estimates were prepared by Outram. In 1795 a decision to build the canal link was deferred and it was introduced as part of an application for an extension of the Peak Forest Canal to Macclesfield. This was the forerunner of the present-day Macclesfield Canal but the original scheme failed, with no more being heard of the plans for a Stockport arm.

In 1800 Wright purchased Brabyns Estate and came to live at Brabyns Hall. He had married his second wife, Mary Wheeldon of Haslin House near Buxton, in 1797 and their son, John, was born in the year they moved to Marple. They also had a daughter who died in 1811. Mary herself died in 1804 and Nathaniel was married for the third time, to Elizabeth, twenty-one years his junior. She died two days after their stillborn son and was buried in 1815. Wright spent the years after the acquisition of Brabyns expanding the Hall and altering and improving the estate.

When England declared war on France, in 1803, Wright joined the Poynton, Worth, Norbury and Bullock Smithy Volunteers, receiving a commission as a Captain-Commandant.

Wright was a contemporary of Samuel Oldknow and, possibly encouraged by his friend's success, he embarked on plans to build a water-powered cotton mill on the Brabyns Estate. He constructed a weir and water race on the river Goyt for this purpose but the plans came to nothing when it was realised that to achieve sufficient head of water he would have to flood half of his land. (Update: this is a popular local story but the truth is more complex and it was actually issues over water rights that scuppered plans for a mill. Visit MLHS's web site for more details). The weir still remains and, to this day, is known as Wright's Folly! During the same period Wright also constructed a stone bridge, called the Scroll Bridge due to the sweeping curved designs carved into its stone parapets.

Wright's Folly

Like Oldknow, Wright was a keen horticulturalist and won Gold Medals for his forestry planting, which included Cypress, chestnuts and poplars. Both men were members of the congregation at All Saints' Church and, in 1816, they were instrumental in the purchase of a second-hand peal of bells from St. Mary's in Stockport. The bells were being replaced, it is said, because they had been loosened by over-zealous celebrations following Nelson's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar some years earlier.

By 1810 Wright was in a position to expand his mining interests and, when the lease for the rest of the Poynton Collieries became available, he was able to take over completely. In 1811 Wright appears to have needed extra capital and signed an indenture dividing the lease with William Clayton the younger, of Worth, who agreed to take a half share. Clayton, who had collieries in Hurdsfield, Haughton and Hyde, also purchased a half share of the "several engines, utensils, implements, matters and things now belonging to the said collieries and coal works" for £818, which was one half of a valuation made by William Sherratt.

It was shortly after this that Wright must have approached the Salford Iron Works regarding construction of a carriage bridge spanning the river Goyt, to open up a passage between his estate and the village of Compstall. With their association now spanning nearly twenty years, it is likely that Wright had become friends with Sherratt, an engineer of considerable talent and reputation. It is easy to imagine Sherratt basing his plans on the innovative designs of Thomas Telford and Thomas Wilson, whose bridges of the period bear remarkable similarities to the one constructed for Wright by the Salford Iron Works in 1813.

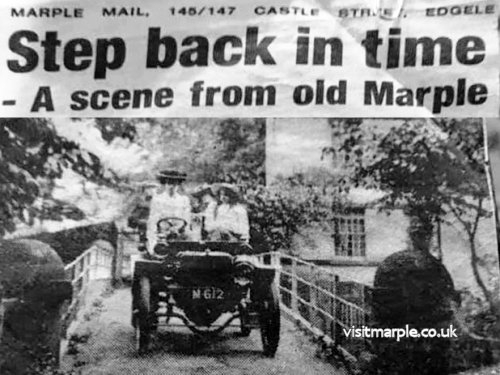

Long after Wright's time, a car crosses the Iron Bridge in 1905.

Wright's partner, Clayton, died in 1816 and left his share of the Poynton Collieries to his grandchildren. One of them, another William, appears to have taken charge and Wright continued in partnership with him until 1818, when he too died, leaving his estates and business interests in trust for his son John.

A marble tablet, made by Lupton of London, was affixed to the south wall of the nave in All Saints' Church - to the memory of Nathaniel Wright Esquire, of Brabins Hall, who departed this life 16 July 1818, aged 58 years. Ten years later, Wright's old friend Oldknow was similarly honoured, when he too passed away. Today both memorial plaques are to be found in the bell tower of the old Georgian Church, which was strengthened and restored when the main body of the church was demolished in 1969.

On 1 January 1826 John Wright withdrew from direct connection with the collieries when he sold his share of the leases to William Clayton for £2300 per year. Clayton also paid £6039 11s for Wright's share of the plant and equipment, this being one half of a valuation made by Thomas Sherratt of Manchester, Iron Founder and son of William, Nathaniel's old friend and business associate at the Salford Iron Works.

The Salford Iron Works

By the late eighteenth century Bateman and Sherratt of Salford were a firm of considerable size, using power-operated lathes and boring engines in the manufacture of textile machinery, steam engines, and a wide range of other products.

Salford Iron Works gates

James Bateman was the founder, and he first appears in the Manchester directory for 1773 as an ironmonger on Deansgate. By 1781 he had also started an ironmongers in Salford and seven years later, in 1788, he was listed as James Bateman and Company, ironmongers, Deansgate; iron founder, Water Street, Salford; iron forger, Collyhurst; and iron founder and forger, Dukinfield. It was during the latter part of this period that Bateman began his association with William Sherratt, who is first mentioned as the contact at Dukinfield Furnace.

The firm's application of iron to new structural purposes was soon illustrated by their making a large 'circular iron weir, near ninety feet span', cast at Dukinfield Furnace, for John Arden, Esq., near Stockport, and said to be 'the first of the kind ever made in this kingdom…it will be found more durable and cheaper than either wood or stone.'

In January 1782 Bateman inserted a long advert in the Manchester Mercury, informing people that he had lately erected an iron foundry (probably the one in Water Street) and had begun to manufacture an astonishing variety of cast-iron goods:

Etna Foundry, Manchester, January 1, 1782, James Bateman, Iron-Monger, Deansgate, Manchester, Begs Leave to acquaint his Friends and the Public, That he has lately erected an Iron-Foundry, and begun to Manufacture a great Variety of elegant Pantheon, Bath, and other Stove Grates; Cast Iron Kitchen Grates, Cylinder, Octagonal, and the new invented Hob or Side Oven, Hot Hearths, Ironing Plates, Laundry Stoves, Pots and Pans of all Sizes in Sand or Loam, for Chymists, Soap Boilers, Crofters, Dyers, &c., Stoves and Pipes of all Kinds for Warehouses, Printers, &c., Furnace Doors and Bars, Velvet Irons, Clock and Sash Weights, Weights of all Sizes adjusted by an exact Standard, Box, Sad and Hatters Irons and Heaters, Waggon, Cart and Chaise Bushes, Iron Wheels for Coal Waggons, Gins and Barrows, Gudgeons and Spindles for Mills, Cogg Wheels of any Size, all Kinds of Shafts, Wheels, Pinions, and Rollers, Paper Screws, Boxes and Rolls for Copper and Slitting Mills, Garden Rollers, Calendar Bowls, Iron Gates and Railing, Iron Doors and Chests, Brass Steps for Mills, and all other Castings to Patterns or Dimensions, with many Articles quite new in the Cast Iron Way.

N.B. The best Price given for Scrap Iron and old Cast Metal.'

By 1791 Bateman and Sherratt were operating in partnership and had purchased additional land on Hardman Street, Salford, for the establishment of a new iron foundry, which would extend their capacity considerably. This was the site that was to become the Salford Iron Works.

William Sherratt was an engineer of considerable ability, particularly in the manufacture of steam engines. In his book, 'A Description of the Country to Forty Miles Round Manchester', published in 1795, J. Aikin made the following observations:

A considerable iron foundry is established in Salford, in which are cast most of the articles wanted in Manchester and its neighbourhood, consisting chiefly of large cast wheels for the cotton machines; cylinders, boilers, and pipes for steam engines; cast ovens, and grates of all sizes. This work belongs to Bateman and Sherrard....Mr Sherrard [sic] is a very ingenious and able engineer, who has improved upon and brought the steam engine to great perfection. Most of those that are used and set up in and about Manchester are of their make and fitting up. They are generally of small size, very compact, stand in a small space, work smooth and easy, and are scarcely heard in the building when erected. They are used in cotton mills, and for every purpose of the water wheel, where a stream is not to be got, and for winding up coals from a great depth in the coal pits, which is performed with a quietness and ease not to be conceived.'

In the same book Aikin also revealed a link between Bateman and Sherratt and the original Iron Bridge, built by Abraham Darby III in 1779, when he wrote:

The quantity of pig iron used at the different foundries in Manchester within these few years, has been very great, and is mostly brought (by canal carriage) from Boatfield and Co's iron furnace, Old Park, near Coalbrook Dale; and Mr Brodie's furnace, near the Iron Bridge, both in Shropshire.'

Bateman and Sherratt were competitors with the legendary firm of Boulton and Watt, who had taken the performance and efficiency of the steam engine to new levels with their double-acting rotative engine. It was a competition that the Salford firm appear to have won in the Manchester area, although they were later found guilty of infringing several of James Watt's patents when the Birmingham firm secured an injunction against them in 1796.

Included in the documentation compiled by Boulton and Watt's during their investigations into the infringements of their patents were details of an engine constructed by Bateman and Sherratt at Sir George Warren's colliery at Bullock Smithy, near Poynton, Cheshire. This is listed as a pumping engine with a single cylinder of 41 inches diameter and 7 ft stroke, which commenced working in August 1795; this is almost certainly the one purchased by Nathaniel Wright.

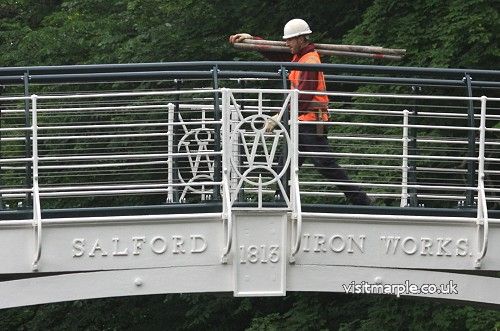

A full-on view of the Salford Iron Works inscription.

Bateman and Sherratt made some of the earliest marine engines, one of which, it is said, was fitted into a barge on the Bridgewater Canal in 1794. In 1799 another was made for a boat nicknamed Bonaparte, designed by the celebrated Robert Fulton. This was built in the Duke of Bridgewater's yard at Worsley for hauling coal barges on the canal to Manchester. The boat proved to be a failure, but the engine and boiler apparently had a long and useful life, for various industrial purposes, until 1851.

With the expiry of Boulton and Watt's patents in 1800, Bateman and Sherratt were able to develop their business vigorously and, perhaps because they made all the components in their own works, they had a reputation for speedy delivery and erection. Coupled with their lower initial cost, this must have helped them to maintain an advantage over Boulton and Watt in the Manchester area and there is no doubt that the firm prospered.

The same view after the restoration project was completed.

At present we have few facts about the history of the Salford Iron Works from 1800 to 1837, when Thomas Sherratt, son of William, died. At this time the works had grown to cover nearly 6,800 square yards, including pattern rooms, casting shops, smiths' shops, fitting-up shops, engine house, gas house and gasometer, crimpers' shop, brass foundry and several other workshops. We know that after Thomas's death his trustees leased or sold the Salford Iron Works to John Platt, who later, in 1845, leased part of the works to William and Colin Mather.

In 1852 Colin Mather entered into a partnership with William Platt, son of John Platt, the latter having died in 1847. This was the beginning of the present-day company Mather and Platt. The company retained the name of the Salford Iron Works and it continued as their home until the new Park Works was opened at Newton Heath, Manchester, in 1901.

Over the next three decades Mather and Platt gradually severed their ties with the Salford Iron Works site and when they completed the transfer of the heavy Iron Foundry to Park Works, in 1938, the premises were sold to Threlfall's Brewery.

Acknowledgements and Further Reading

The following sources have been used in the compilation of this booklet and are recommended for further reading if a greater understanding of the topics covered is desired:

Brabyns Hall and Park – Peter Bardsley and Ann Hearle, ISBN 095227613, October 1995: Marple Local History Society.

Exploring Telford Web Site - Richard Foxcroft (page no longer exists).

The Iron Bridge – Neil Cossons & Barrie Trinder, ISBN 2390001877, 1979.

Stockport Heritage Magazine – Summer 1991 issue.

Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution A. E. Musson & Eric Robinson, ISBN 719003709, 1969: Manchester University Press.

Marcel Boschi's History of Mather and Platt Ltd. (https://sites.google.com/site/historyofmatherplattltd/)

Poynton A Coalmining Village; social history, transport and industry 1700 - 1939, by W.H. Shercliff, D.A. Kitching & J.M. Ryan, 1983. ISBN 0950876100: Published by W.H. Shercliff. On-line version (http://www.brocross.com/poynton/conten.htm)